March 18th, 2020

I include Alfred Wegener in this catalog because he is a man who was NOT, strictly speaking, ahead of his times, even though many people believe that he was.

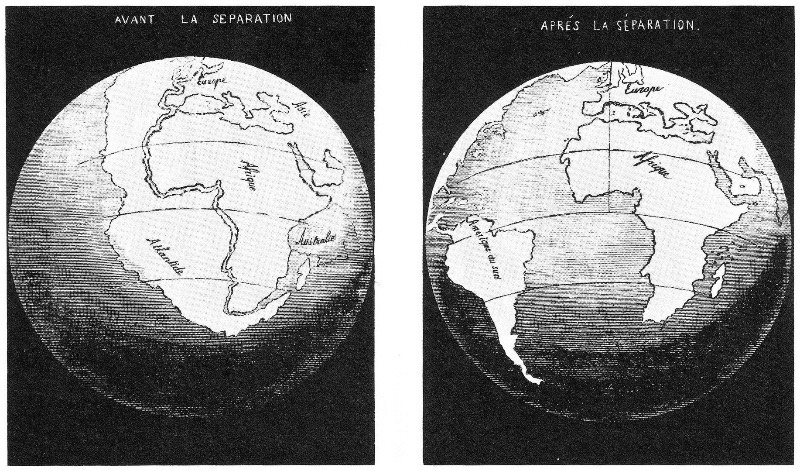

Wegener’s story begins long before he was born. Throughout the 19th century, a number of scientists noted that the coastlines of the Western Hemisphere seemed to match up with those of Europe and Africa. Here’s a drawing from 1858:

It certainly looked suspicious, but there wasn’t much to go on beyond the maps. Accordingly, most scientists treated it as an interesting oddity that remained outside the realm of scientific confirmation—for the time being. But speculation was rampant.

In 1912, Alfred Wegener published a scientific paper presenting his version of the hypothesis, which he dubbed “continental drift”. He had collected a large amount of ancillary evidence to support his hypothesis; he later presented a fuller version of his hypothesis in a book in 1916.

Wegener noted that fossils of a particular species of fern had been discovered in Antarctica. How could this happen, he asked, if Antarctica had not moved from a tropical location to the South Pole? He also presented examples of fossils of similar species found in both Africa and South America. Again, he asked, how could that species have crossed the Atlantic Ocean?

He had even better evidence in the form of rock types. He clearly showed that rock types in America’s Appalachian Mountains closely matched rock types in Scotland. Wegener found similar examples of matching rock types in South American and South Africa. He felt that the evidence he had collected was enough to support his hypothesis.

But one fatal flaw prevented scientists from accepting Wegener’s hypothesis: he couldn’t answer the question, “What force could possibly shove entire continents across the face of the planet?” Clearly any such force would have to be stupendously powerful, and we should be able to see the effects of such a stupendous force somewhere on the surface of the planet, but no such evidence was available. Yes, Wegener’s evidence was impressive, but accepting his hypothesis required a leap of faith too great for most scientists to accept.

All through the first half of the Twentieth Century, more evidence piled up, showing similar fossils and similar rock types on both sides of the Atlantic. Still, in the abscence of a plausible mechanism to drive the motions, scientists remained skeptical.

The first big break came in the late 1950s when scientists began measuring the magnetic fields of undersea rocks with airplanes towing large magnetic sensing arrays. To their astonishment, they found a pattern of magnetic stripes on the ocean floor. They altered in direction. A North-South stripe would have South-North stripes on either side. The pattern was centered in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

The clincher came when they sent the first deep-sea submersible vehicle, the Alvin, down to see what was in the center of the Atlantic. There they found the mid-Atlantic ridge, a region where lava pushes up to the surface from deep below. This is the process that pushed the continents apart.

Now that scientists had a clear mechanism causing continental drift, they immediate embraced the hypothesis. Wegener, it turns out, had been right all along. But he just didn’t have convincing evidence, so he was still wrong.

Right?