The face rivals language as the most important channel of human communication. Artists have known this from time immemorial; they have devoted vast energies to depicting the human face, be it in a bust or a portrait. The most famous painting in the world is of the face of somebody we know little about:

Our face is our identity; it is the face that we present to the world. Movies are especially enamored of showing faces. Here’s one of the most intense, action-packed sequences in Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope

Many years ago I went through this sequence frame by frame, counting how many frames were devoted to action shots (roaring turbo lasers, screaming TIE fighters, grand explosions, and the like) and how many were facial shots.

The result I got will surprise you: there were just as many frames showing faces as showing action. The faces communicated as much excitement and fear as the violence.

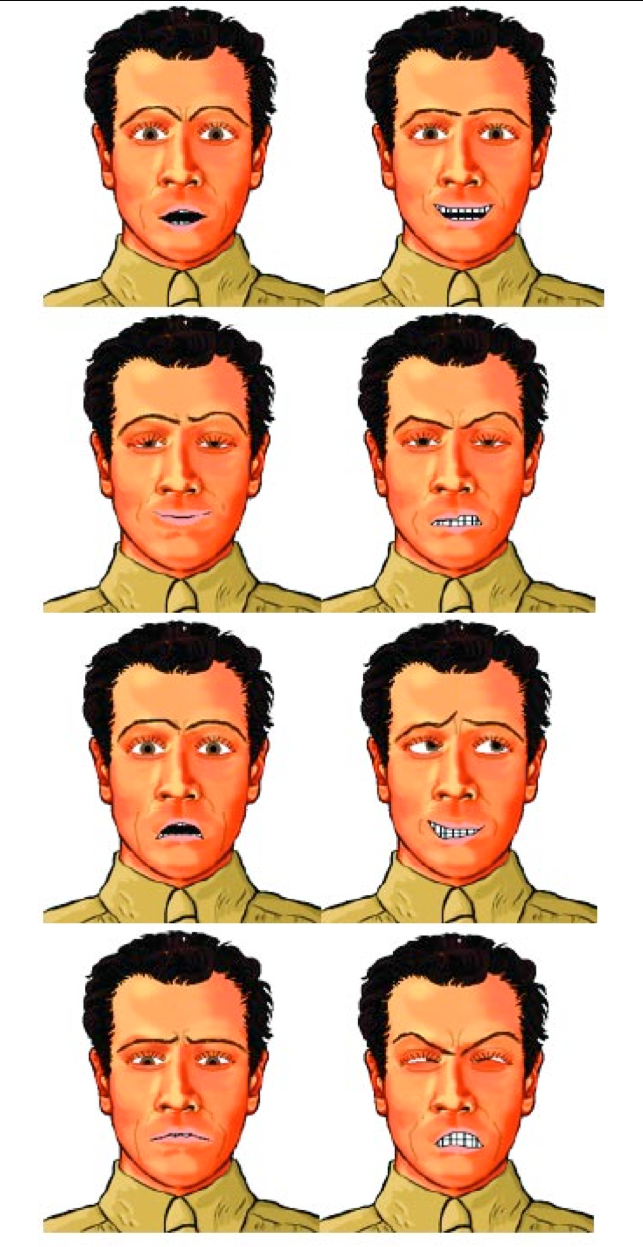

Actors study human facial expression, and great actors are masters of expression. But the intensity with which actors use facial expressions depends entirely upon the dramatic context. Here’s Alan Rickman, one of the great actors of our time, using four different intensities of facial expression in four different movies:

Abstracted Facial Expressions

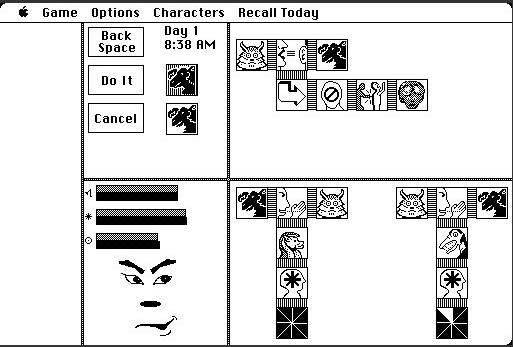

Any form of interactive storytelling absolutely, positively MUST include the use of facial expression. In the early years, we didn’t have the technical capacity to put emotional expressions onto the faces of our actors. Back in 1987 I tried to cope with this problem by splitting the actor’s face from the emotional expression, like so:

The emotional expression is in the lower panel. I tried something similar with the Storytron technology:

This simple approach was useful back when we didn’t have the technology to apply emotional expressions to individual faces. Now we do; this is obsolete.

2D Facial Expressions

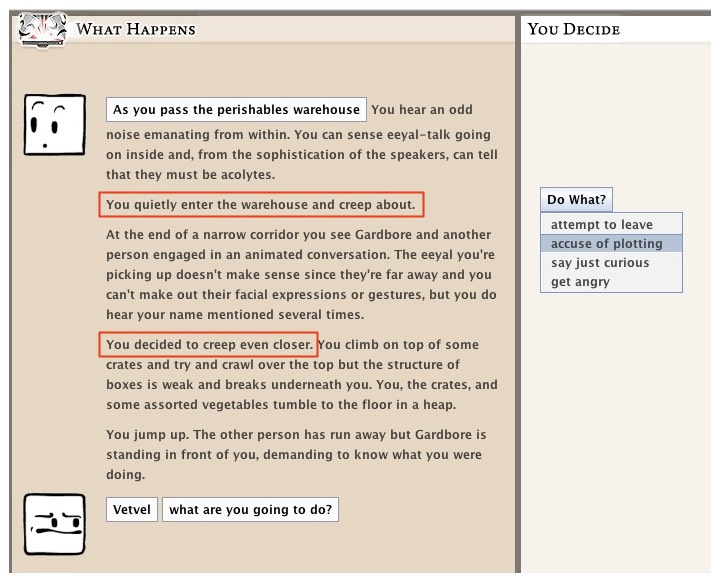

Another approach was inspired by Susan Brennan’s work on caricatures in the early 1980s. My first effort in this direction was with my second Arthurian game, Le Morte D’Arthur, which I wrote during the early 1990s. Here’s a black and white rendition of one of the faces used in that design. That face you’re seeing could show different emotional expressions.

I used much the same technology with the Erasmatron in the 1990s:

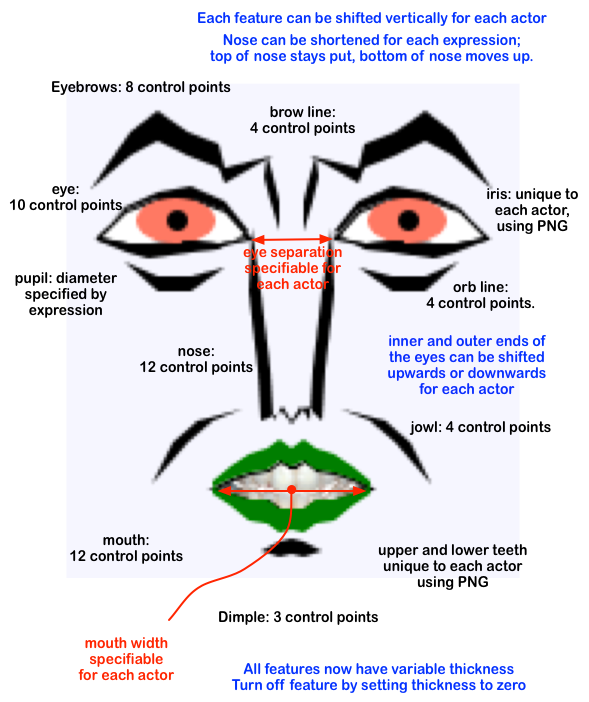

I used the technology in Storytron; here’s an illustration of the graphical system:

I also built a face editor for Siboot:

Here’s a description of the Face Editor system I built for Storytron.

From 2D to 3D

These are all two-dimensional representations of the face, which imposes a serious constraint. Many facial expressions rely on rotations of the head:

I was able to come up with a hack that partially addresses the problem, but the only true solution is to go all the way to 3D representation of the face. We certainly have the technology to do that:

But note a crucial distinction between the videogame faces and the Shrek faces: Shrek’s face are alive with emotion, bursting with energy. The videogame faces are dull, dead, and boring. Yes, you can make out a trace of emotion on a couple of the faces, but for the most part they’re just staring blankly. The problem here is realism: all of our face generation technologies are based on anatomical facts, not artistic principles.

Comics and Cartoons

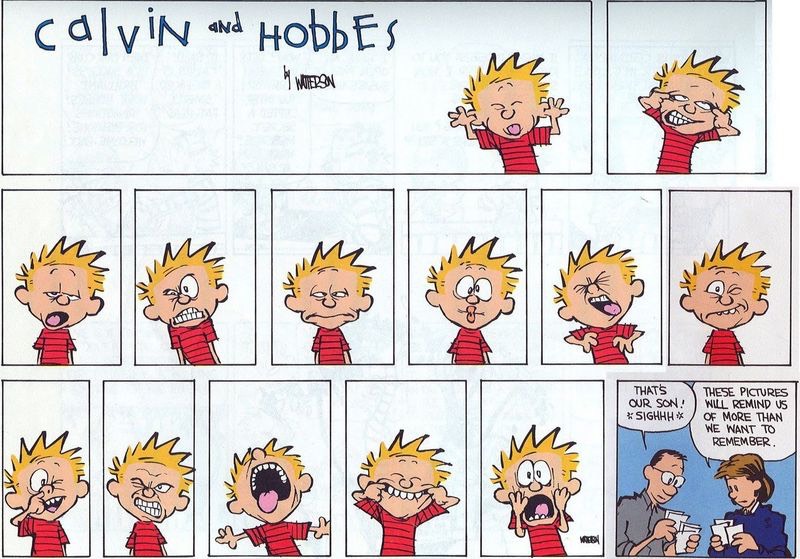

The faces above are all wrong for interactive storytelling. This is more like what we need:

Or perhaps something like this:

These characters have more life and energy to them than any photorealistic representation. Or how about this as an example of a character that violates just about everything we know about human anatomy:

Yes, someday we’ll want facial imagery appropriate to a truly sophisticated, subtle piece of serious drama. But for now, we need imagery appropriate to the primitive interactive storyworld that we’ll be able to build.

Dynamic expressions and micro expressions

Human facial expression is immensely complex; the static expressions I present above do not begin to capture the richness of human facial expression. Much expression is dynamic. For example, recall this fragment from the first Shrek movie. Shrek has an arrow in his butt; Fiona pulls it out rather angrily. Here’s her face during that sequence:

These 11 frames span about 1.5 seconds; she how her expression transforms from anger to a smirk during that time. The two expressions combine to comical effect—all in less than 2 seconds.

Even trickier are micro expressions: rapid expressions that dart across the face in perhaps 50 milliseconds. They are involuntary and therefore revealing of true feelings. Unfortunately, they take place too quickly to be shown adequately in most video imagery. At 30 frames per second, a microexpression will span just two frames. We can afford to leave microexpressions for future generations of interactive storytellers to tackle.