Now at long last we get to the real meat: the algorithms for interpersonal interaction. These are the means by which you will express your artistic interpretation of the human condition. This will not come easily to you, as it will require a completely new way of thinking about art. Instead of thinking about art as describing Object, you will need to think about art in terms of Process. While this is strange, it is immensely more powerful than any previous medium of expression. Leonardo could only show Mona Lisa’s smile; with algorithms, you can express how she acts. Instead of merely looking at her, the player can actually interact with her. Huckleberry Finn steps out of the static pages of the novel and becomes an active character, responding to the player’s behavior. Instead of merely passively watching Luke Skywalker go through his paces in a movie, the player can poke and prod at him, actively probing his character.

This represents a huge leap in artistic expression; instead of remotely talking about the human condition, we can actually make it happen. We can empower our audiences to see people actually responding to new situations. But its radically new possibilities make it that much more difficult to appreciate. Artists have always had total control over every tiny Object of their expressions. With this new medium, the artist must operate at a higher artistic level of abstraction, attending not to the Object-manifestations of the human condition but the actual processes of the human condition.

Very few storytellers can comprehend this more abstract approach to storytelling. Stories have always had plots. Plots are a form of data — that is to say, Object. The traditional storyteller controls every detail of the plot. This leads to a sad misunderstanding on the part of artists attempting to work in interactive storytelling.

The artist maintains that the plot must be precisely specified in order to give the story dramatic power. Yet, if the player is to interact with the story, then the player must be able to alter the plot. By altering the plot, the player will ruin the artist’s carefully designed dramatic flow, and the story will be ruined. Therefore, these artists claim that story and interactivity are incompatible. You can’t have an interactive story, they insist.

They’re right: an interactive story is impossible. But the answer lies in a simple realization: a story is data — Object. Recall my definition of interaction:

Interaction is a cyclic process in which two agents alternately listen, think, and speak to each other.

Interaction is a Process. You can’t interact with Object; you can only interact with Process. Story is Object, and therefore non-interactable. But storytelling is a Process. Storytelling can be interactive, where story cannot. That’s the answer to the problem. You are not Shakespeare sitting down to create a beautiful piece of data. You are grandfather sitting down with little Molly at bedtime.Sure, you could just recite one of the many children’s stories you know. But what if Molly interrupts you with her own preferences? Do you snarl, “Shut up, brat, you’re messing up my carefully planned plot!” No, you alter the story in real time to suit Molly’s interests. You interact with Molly. You have no idea when you sit down exactly what the plot of the story will be. What you do know are some basic dramatic principles — processes — that govern the development of any story. You are better than a television playing Frozen or Brave: you can shape the story to meet Molly’s needs. Molly will treasure those special stories you told her, the stories that you and Molly made together, just for Molly, for life. She’ll probably forget Frozen and Brave in a few years.

To do interactive storytelling on a computer, you must express those dramatic principles on the computer. The ironic thing is that this process is more direct than traditional storytelling. Here’s how traditional storytelling works:

The artist has a vision of the human condition to convey. The artist first translates that vision into a story. The artist then communicates the story to the audience. The audience receives the story and then translates that back into an appreciation of the human condition. In other words, nobody cares about Luke Skywalker, but everybody can appreciate the challenges of becoming an adult. Nobody cares about Huckleberry Finn, but we all crave a better understanding of how we can cope with the evils of society. It’s not the details of the story that we care about, it’s the principles. All the plot details that the artist sweats are ultimately of no significance — what matters are the deep principles that those details communicate.

So why should we spend so much time sweating details when interactive storytelling allows us to express the principles themselves? Why use such an indirect method?

I confess, I am overstating the case. In interactive storytelling, we do indeed express the basic dramatic principles that we seek to communicate, but we must still design the software to translate those principles into observable events. In fact, that process is presently more difficult than simply figuring out a single story. So my simplification is grossly misleading. But here’s a way to appreciate the significance of this new way of thinking:

You were born in 1940, and were taught arithmetic using the paper-and-pencil methods that have been used for 500 years. Then in the 1970s there came along these little electronic calculators; they were all the rage. Your younger colleagues at work encouraged you to get one. But you have objections; these things are much harder to use than the paper-and-pencil methods.

“How do you multiply two numbers together?” you ask.

“Simple!” your co-worker replies. “First you key in the first number on the keypad.”

You grumble but it doesn’t seem so hard.

“Now you press the multiply button” she tells you.

OK, that’s easy enough.

“Now key in the second number.”

You start to do so, but the first number disappears. “Where’d the first number go?!?!?” you demand.

“It’s still there, it’s just hidden in the calculator’s memory.”

“What do you mean, ‘hidden’? Where is it? How can I multiply it if it’s gone?”

“Don’t worry! Just key in the second number” she advises, sounding a little impatient with your ignorance.

You key in the second number. “Now what?”

“Just press the equals sign!”

You press the equals sign. A new number appears. “What’s that?” you ask.

“It’s the answer! You did it!”

You’re not impressed. “How do I know that it’s the right answer?”

“It’s a computer. It’s always right.” Now she’s getting exasperated.

“But how do I remember what the first two numbers were? They’re gone, so I can’t check them.”

Now she’s definitely losing her patience. “You don’t need to remember them. You have the answer now.”

You decide to end the conversation before things get ugly. This damn calculator is confusing. You’re going to stick with the tried-and-true paper-and-pencil methods that have always worked for you in the past. You’re in for a real shock in ten years when personal computers show up.

Calculators require that we think about arithmetic in more indirect, abstract ways. They’re more powerful than the old ways, but they require you to make big changes in the way you think about arithmetic.

If that doesn’t convince you, here’s a completely different approach. As a storyteller, you are something like a god, creating a special universe that powerfully shows the truth of our lives. As a god, you control every aspect of the story: the characterizations, the events, the dialogues, and the plot. You specify every detail. After all, it’s YOUR universe!

Now let’s analogically jump to the real world as seen by a religious person. That world has a god, too, who also controls everything. That god decides when and where the rain falls, where the lizard crawls, where the leaves grow, and of course what people do. After all, this god is omnipotent, right?

But wait! A god who controls every aspect of the universe controls our behavior. There’s no room for free will in this god’s universe — everything is decided in advance. Humans are just automata running according to the god’s dictates.

Yuck! We don’t like the thought that we lack free will, but how do we reconcile free will with an omnipotent god? Christian theologians struggled with this paradox for centuries. Eventually a solution arose: God doesn’t dictate the path of every atom, the course of every raindrop, every step of the lizard, or every decision by a human being. Instead, God dictates the broad principles under which the universe operates. Instead of rushing around directing every falling raindrop, God says simply, “Let there be gravity!” and then lets gravity pull the raindrops down. God does not direct his human puppets to sin; instead, God establishes the rules according which the human mind operates, and then allows humans to make their own decisions. God still controls the universe, but in a more abstract and indirect fashion.

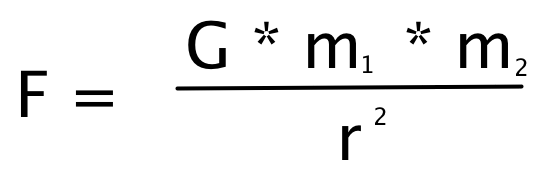

In order to pull this off, God must use mathematics. He creates the law of gravitation:

as well as all the other laws of physics that determine the operation of the universe.

The moral of this story is this: if you want to be a competent god creating your own universe, you’re just going to have to think in more abstract, indirect, and mathematical terms. Have you got what it takes to be a god?