September 29th, 2022

Now that I have begun the process of releasing Le Morte D’Arthur to an ever-widening audience, I am encountering some unhappy feedback, which I shall boil down to the plaint that “It’s not what I expected.” There are many flavors of this complaint. A great many arise from expectations unconsciously engendered by experience playing games. Games are such a thoroughly-established genre that most people these days cannot see beyond the artificial assumptions built into games.

I’ll first describe three such conventions. One is that the fundamental goal of the interaction is for the player to win. This is analogous to the assumption that a story should have a happy ending. But as far back as Aristotle (and surely much further back) we recognized two broad classes of stories: comedies and tragedies. Aristotle did not mean by ‘comedy’ a story that left you laughing uncontrollably; he meant a story with a happy ending. A tragedy, by contrast, had an unhappy ending. Americans don’t like tragedies, but in fact some of the greatest stories are tragedies. Greek literature includes many powerful tragedies: the Iliad, Oedipus Rex, and Prometheus Bound, for example. Shakespeare turned out as many tragedies as comedies, among them Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, and Julius Caesar. Modern literature teems with tragedies: Of Mice and Men, Lord of the Flies, A Farewell to Arms, Les Miserables, Frankenstein, Death of a Salesman, and many more. Cinema has had many powerful tragedies, including All Quiet on the Western Front, Sophie’s Choice, Se7en, The Green Mile, Titanic, and Hachi: A Dog’s Tale.

So why shouldn’t a game always end in failure? After his great victory in the Franco-Prussian War, which he led, the great German general Helmuth von Moltke was told by an admirer that his reputation would rank with such great captains as Napoleon, Frederick or Turenne. He answered ‘No, for I have never conducted a retreat.’ Heroism is best demonstrated in the management of disaster, not the triumph of victory. Yet games don’t acknowledge that profound truth.

The second convention is that the player’s actions should all be directly tied to their success or failure. The player will make hundreds of decisions during the course of play; every one of these decisions, according to convention, should have a clear effect on the outcome, either positive or negative. I question this convention — why shouldn’t the player learn that some actions are irrelevant to the outcome? Is not the discovery of what is relevant and what is not a crucial part of learning?

The third convention holds that the learning curve of the design should be smooth. Each game, according to this convention, requires the mastery of scores of small skills that must be mastered in order to win. The player must learn when to use the rifle and when to use the rocket launcher, or when to flee and when to charge, or which opponents are most difficult and which opponents are easily beaten.

But what if, instead of requiring the player to master a hundred small skills, the player must instead learn one big lesson? What if the meaning of the design is a huge idea that will trigger a profound “Aha!” moment for the player? In such a case, the learning curve is necessarily a single huge step — about as great a violation of convention as conceivable. Does not this convention condemn designers to small ideas?

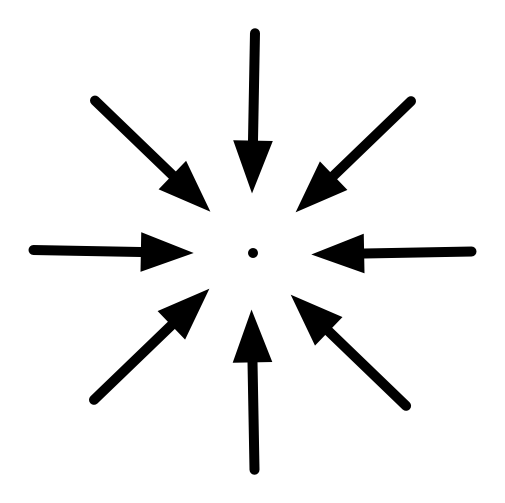

Progress is change.

Change violates conventions.

Therefore, violating conventions is necessary to progress.

The history of human expression powerfully affirms this process. Examples:

Painting

Painters have been violating convention since there were conventions. Caravaggio’s Death of a Virgin (1606) was scandalous because it depicted Mary as a fairly normal woman, not the haloed Mother of Christ conventionally represented at the time. Gustave Courbet's The Origin of the World (1868) created a continuing scandal because it shows a closeup of a woman’s vulva and abdomen with her legs spread. Again, this violated convention and the painting was squirreled away. In 2011, a Danish artist posted an image of the painting on Facebook as part of an artistic discussion; Facebook removed the post and sanctioned the artist. Facebook ended up losing the court battle over its actions.

Of course, Pablo Picasso has to be included in any such discussion, because he violated conventions left and right. His attempts to show the fullness of the human face were widely considered monstrosities. His most controversial piece was probably Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (1907), which launched a major artistic movement called Cubism. When it was first shown, the painting was loudly disparaged, but within a few decades, Picasso’s ideas had been embraced.

Literature

Before the invention of the printing press, books were horrendously expensive, so there was no room for convention-defying experiments, but once a buying public was assembled, authors began to push the boundaries of conventions. The first such experiment was Desiderius Erasmus’ The Praise of Folly (1511). Its satirical but accurate skewering of European hypocrises set half of Europe laughing and the other half sputtering in indignation. It was probably the first “mass-media best-seller” in history and it earned Erasmus a great reputation.

I cannot provide an adequate summation of the immense history of convention-defying literature; I shall instead offer a few salient examples.

Ambrose Bierce’s An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge (1890) broke with the convention of third-person objective point of view, offering instead an entirely subjective (and ultimately false) point of view.

Ulysses (1922), by James Joyce shattered conventions of objectivity; the entire novel is an extended stream of consciousness, a form that had been toyed with previously, but Joyce developed the concept to its full realization.

Of course, many, many novels have been controversial because they challenged conventional moral standards, but I do not include them here because they did not advance literature as a medium of artistic expression.

Music

Music has also had a long history of convention-defying innovations. As with literature, the history of music is immensely complex, especially because the Christian church encouraged the composition of sacred music from early times. The first broad genre resulting from this was Gregorian chant; then came polyphony (multiple voices in a single piece). From there, multiple lines of development proceeded, but essential to each of these was the violation, to greater or lesser degree, of previous conventions. As the popularity of music expanded, more and more composers created more and more compositions, and innovation flourished. New instruments and the development of larger groups of musicians expanded the medium even further. It’s difficult for an untutored person like myself to identify individual leaps, as many of the innovations over the last 400 years developed incrementally.

But I can point to one clear example of convention-defying innovation. With the expansion of musical performance, audiences grew impatient with the “same old stuff”. The existing conventions enabled them to anticipate where the music was going and felt impatient. Beethoven was the master of setting up audience expectations (as defined by the conventions of the day) and then violating them. A good example comes at the end of his Fifth Symphony, where he presents two false endings before the genuine ending. As you listen, you tell yourself, “Ah, this is the end” — and then he keeps going! Have a listen:

This set off a wave of innovation as composers set about toying with audience expectations based on existing conventions. The culmination of this evolutionary process, as I understand it, came in 1913 with the premier of Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring”. This piece had such radical violations of musical conventions that it very nearly triggered a riot (although the even more unconventional choreography played a larger role in infuriating the audience). Stravinsky is now regarded as one of the greatest, if not THE greatest, composer of the 20th century.

Classical music has not, in my vulgar opinion, done well in the last hundred years, but its creative energy has been overtaken by pop music. Much of this energy came from African music as manifested in America. Such music was long dismissed as ‘ignorant’, but all through the first half of the 20th century it spread, and blossomed in the 1950s with rock and roll, an invention of black musicians in America, along with jazz and the blues. White musicians took up rock and roll and extended it, in the process triggering a wave of musical innovation, most strikingly in the strong role taken by the underlying beat. Musical groups such as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones triggered a musical Golden Age that continued into the 70s. This music was not at all like popular music of the 30s and 40s, which centered on lower-energy music with strong vocals. The Greatest Generation that had survived the Depression and fought World War II found the new music most distasteful — but their tastes were swept aside by the innovation of rock and roll.

Innovations continue; I cannot keep up with all the changes in modern music. I will mention, however, Philip Glass, whose endless repetitions with slight changes impress me. See, for example, the opening of Koyaanisqatsi.

Cinema

Cinema has a shorter history than any of these other media of artistic expression, but its popularity has driven a great deal of innovation. Its initial efforts were crippled by the age-old expectation that it conform to the nearest thing to which it could be compared: the theater. Thus, early cinema was little more than “canned theater”. They placed the camera in a prime location in the audience seating and then performed the play while the camera recorded it. There’s an important lesson here: people just can’t break loose from their conventions. It takes a rebel to make change.

That rebel was D.W. Griffith. Now, Griffith did not invent any of the revolutionary techniques with which he has been credited — but he employed them more methodically and more frequently than anybody else had at the time. Concepts such as the facial closeup and the moving camera dominated his later films. Moreover, he made so many films that he was an irresistable force in the industry. He was also careful to select actors who had some experience in theater — but not too much, lest they be compromised by too much adherance to the conventions of the theater.

D.W. Griffith was followed by a parade of brilliant talents who kept violating conventions almost as soon as they were established. Most movies in the early days employed long, continuous shots — then creative people found the power of using shorter shots at higher frequencies. Point of view shots, presenting the view as seen by the actor, became more common.

I don’t know enough about the history of cinema to present a concise summary of the evolution of this medium, but I can mention one example of innovation in shot length. Here’s a classic clip from the end of an episode of The Twilight Zone from the 1960s. Note how long the shots are.

Now let’s jump forward just 20 years, to the early 1980s and the movie Raiders of the Lost Ark. Here’s the opening 3 minutes. The opening shots are definitely shorter than those in The Twilight Zone clip, but then Spielberg and Lucas announce a major innovation in cinema with a sequence of shots. In just seven seconds, they roll nine different shots:

Bad guy sneaks up behind Indiana Jones, pulls his gun, and cocks it.

Indiana Jones hears the gun cock and tilts his head

The bad guy aims his gun...

Indiana Jones grabs his whip and whirls around

We see his hand raising the whip behind him

His hand, holding the whip, comes down. The other guy winces in pain seeing what the whip does.

This is the only full shot that shows the whole picture.

The bad guy winces in pain after being hit by the whip

His gun falls into the creek.

This entire sequence takes about seven seconds — that’s less than one second per shot. Indeed, at least two of the shots are so short that few people are consciously aware of them — when asked what they saw, they rarely mention either the fifth or the sixth shot.

This was possible only because a new generation of viewers, raised on television in the 1950s, was more “video literate” and could understand the fast sequence. Their parents could not.

The point

So, what’s the point of all this, and what does it have to do with interactive storytelling? The point concerns the feedback that I’m getting about Le Morte D’Arthur. A disappointingly large fraction of the feedback I am getting reflects conventions from the games industry, conventions that are irrelevant to Le Morte D’Arthur. I don’t want to reject this feedback; I need all the help I can get, and the fact is that there AREN’T any reviewers with experience in interactive storytelling; these games people are the closest I can get to informed critics. But filtering their feedback correctly will be difficult. I must somehow translate their feedback into useful form, a task requiring a great deal of abstract thinking.

If you would like to learn more about the evolution of artistic media, read “The Creators: A History of Heroes of the Imagination” by Daniel J. Boorstin.

Necessity Versus Sufficiency

There will be silly readers who misunderstand my point here, accusing me of grand egotism for comparing myself with the giants of art. When I assert that change is necessary to artistic progress, I am not saying that change is sufficient for artistic progress. History sputters with tales of idiotic innovations that changed nothing. I am not claiming that, because my work is different, it must be good. Indeed, the great majority of innovations are crap. My concern is that innovation is usually met with some disdain that blinds the audience to any merits the innovation might have.