Contents

Changing Graphics

Chris Crawford

Letter

Dave Menconi

The “Perfect” Adventure Game Design

Corey and Lori Cole

A Review of deBabelizer

Aaron Urbina

“The Wonderful Power of Storytelling”

Bruce Sterling

An Approach to Plotting Interactive Fiction Part II

Scott Jarol

Editor Chris Crawford

Subscriptions The Journal of Computer Game Design is published six times a year. To subscribe to The Journal, send a check or money order for $30 to:

The Journal of Computer Game Design

5251 Sierra Road

San Jose, CA 95132

Submissions Material for this Journal is solicited from the readership. Articles should address artistic or technical aspects of computer game design at a level suitable for professionals in the industry. Reviews of games are not published by this Journal. All articles must be submitted electronically, either on Macintosh disk , through MCI Mail (my username is CCRAWFORD), through the JCGD BBS, or via direct modem. No payments are made for articles. Authors are hereby notified that their submissions may be reprinted in Computer Gaming World.

Back Issues Back issues of the Journal are available. Volume 1 may be purchased only in its entirety; the price is $30. Individual numbers from Volume 2 cost $5 apiece.

Copyright The contents of this Journal are copyright © Chris Crawford 1991.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Changing Graphics

Chris Crawford

Our industry has seen three phases with respect to the quality of the graphics we use, and a fourth will be coming soon.

ROM and Casette Graphics

During the first phase, in 1979-82, most games were sold on ROM or on casette; in either case, you just couldn’t put a lot of stuff in there (4K to 16K was typical) so the graphics were necessarily quite limited. Of course, the display resolutions were also very low, so you could get a screen or two out of 8K.

Floppy Graphics

The second phase started around 1982 when a significant fraction of the installed base had floppy disk drives. This permitted game designers to use floppies as their primary delivery medium, and the amount of graphics that we could deliver jumped up to the neighborhood of 80K - 140K, a ten-fold increase. This was especially fortuitous, because the screen resolutions did not increase concomitantly; thus, we were able to pack several dozen screens’ worth of graphics onto a floppy, using primitive compaction techniques. This phase lasted until about 1987.

Hard Disk Graphics

By 1987 two new developments had changed things dramatically. First, the 8-bit machines had been supplanted by the 16-bitters. This meant that we had more processing power. It also meant that we had more display space. The simple black-and-white display on the original Macintosh, for example, required 21K worth of image.

Another big change was the triumph of the hard disk. By 1987 this was standard equipment on home computers. Initially this created a problem for game developers: we couldn’t require the user to boot from our floppy, which in turn shot down most of our best copy-protection schemes. The advent of the hard disk spelled the doom of on-disk copy-protected software.

The positive value of the hard disk did not become evident until perhaps 1989, when the size of computer games, as measured by the number of floppies in the package, began to rise sharply. Prior to 1989, most games were one-disk affairs. But then we started to see more multi-disk games. The user was expected to install the files from the floppies onto his hard disk, and then play the game from the hard disk.

The constraining factor was the price of floppy disk space. It had been about $2/megabyte in 1988; by 1990 it had fallen to $1/megabyte. Because most other expenses are fixed, a game publisher can afford to spend about $2 on floppies for a $40 game, $4 for a $50 game, and $6 for a $60 game. The combination of falling disk prices and rising game prices made possible an explosion in the sizes of games.

Almost all of this growth has been in graphics and sound. Consider the following table of my own products:

Year Product Object Total Product

Code Size Size

1985 Balance of Power 100K 181K

1986 Patton Versus Rommel. 81K 304K

1987 Siboot 80K 273K

1989 Guns and Butter 153K 522K

1990 Balance of the Planet 122K 1371K

1991 Patton Strikes Back (est) 150K 4000K

In six years the object code has fallen from 55% of total product size to 4%.

Speed considerations

There is another factor to consider: hard disk accesses are fast enough to permit substantial use of graphics that are pulled in from the hard disk only as needed. We keep an animation file on disk, with the first frame of the animation in RAM; when the animation is called for, we pop up the first frame and run to the hard disk. By the time the user’s eye has registered on the first frame, the animation is ready to begin.

The Next Phase: CD-ROM Graphics

CD-ROM and the various graphics compression standards (JPEG et al) will change things again, making possible another big leap in graphics. But that remains several years in the future...

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Letter

Dave Menconi

I read Greg Costikyan's article in the last issue of the Journal with great interest. In the fifteen years I have been programming, this is not the first time I have heard that, in the future, programmers will be out of a job, replaced by the machines we program — although I must say that this is by far the most elaborate such prognosis. It seems that, every time a new programming language or new development in computer science is made available someone is bound to suggest that now, at long last, programmers have been rendered obsolete. Finally, the age of the user has begun. To date none of these predictions has come true. Indeed, each advance allows programmers to use their skill to accomplish even more.

The simple truth is that programmers won’t be put out of a job by any technological whiz-bang. We have total job security.

Back when a computer had 32 kilobytes of memory, 100 kilobytes of permanent storage and ran at 8-16 megabits/second transfer rates (CPU to RAM) the challenge was to push the machine as hard as you could to get something decent. To do that you had to have a deep understanding of the hardware and software on the system.

Now that computers have at least half a megabyte of RAM, many megabytes of permanent storage and have transfer rates of around 160 megabits/second, we have exactly the same challenge. The only difference is that the definition of “decent” has changed. What was a hit before will no longer impress anyone. And we meet the challenge in the same way — we develop a deep understanding of all aspects of the hardware and software.

Certainly, smart programmers use higher level languages but the very best programmers are capable of using assembly language, of programming the registers in the video interface and of programming right down to the bare metal when necessary. And it is necessary more often than one would expect because while the hardware and software have become vastly more powerful, the users have grown commensurately more demanding. Computers are three orders of magnitude more powerful than they were 10 years ago and the cutting edge of our craft is still reserved for programmers.

I have no doubt that 10 years from now computers will be at least 3 orders of magnitude more powerful than they are today. Improvements in hardware and software will make the things we consider hot today child’s play for the programmers — and nonprogrammers — of the future. But the users will not accept 10 year old programming on their super powerful machines. I suggest that the person who understands the hardware at a deep level will always have a big edge on those who depend on the software to do it for them.

To suggest otherwise is at best fanciful. You might just as well suggest that a fine artist who paints in oil doesn’t need to learn all the technical details of his art — the pigments, the brushes, the surfaces, the techniques — because we’ve built a painting machine that will do it all for him. Far from making his job easier, such a painter would have to know all the things he had to know before PLUS the idiosyncracies of the painting machine! All the machine would do is separate the artist from his medium.

As another example, it may come to pass before long that computer will be able to generate meaningful prose. Do you honestly believe that writers will be put out of work by such a machine? Someone will still have to determine what the subject of the prose will be and guide the machine to produce anything worthwhile. Perhaps computers could write police reports or do routine paperwork but the true writers of the day will have nothing to fear from a computer writer. Likewise, great programmers will have nothing to fear from easy-to-use development systems.

Far from putting the programmers out of work, I see the powerful machines of the future freeing programmers from the mundane tasks that they now must perform. All the make-work can be relegated to the non-programmer, allowing the programmers to push the hardware envelope even farther. a

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________The “Perfect” Adventure Game Design

Corey and Lori Cole

At the 1991 Computer Game Developers’ Conference, we hosted a workshop entitled “Design the Perfect Adventure Game.” The purpose of the workshop was not so much to actually design a game as to allow the participants to discover ways to design adventure games. We were overwhelmed when our little hands-on workshop drew over 50 people, but the process seemed to work out despite the crowd.

We feel that a good adventure game should have good writing as its foundation. Therefore, the point of this workshop was to teach the elements of fiction writing through the process of designing an adventure game. The five elements we focused on were Plot, Theme, Setting, Mood, and Character Development. We included an article in the Proceedings which described the elements and questions to generate ideas.

Our purpose of holding this workshop was to develop the group synergy of people working towards a common goal. It was to bring together a diverse set of people from different companies and backgrounds to share their opinions in a constructive manner, with the stress upon cooperation and consideration for others. Thus, in order for us to achieve our personal goals, the workshop had to be entertaining as well as educational. We feel we met our goals pretty well. The workshop was fun.

We started by presenting the situation — participants were part of a design team for an adventure game. They had unlimited development resources, leading edge technology available, and marketability was not an issue. They were to create a game that each of them would like to play.

After we described the game design elements that would be considered — Plot, Theme, Setting, Mood, and Characters — the participants voted on how much time to devote to each category. Highest priority was given to Plot, followed by Theme and Characters, with Setting and Mood considered least important.

So we started by trying to develop the plot of the game. It quickly became apparent that it is almost impossible to develop a story without knowing its theme or setting. Most of the initial suggestions for plot lines fell more closely into the realm of themes — ideas for what the story should accomplish, rather than the story itself. A number of themes ranging from saving the Earth from pollution to “a mindless shoot-’em-up” were suggested. The most popular theme proved to be “You’re in a quest for dreams, but it turns into your worst nightmare.” This is a strong theme with built-in conflict, and potentially a lot of room for character action and interaction.

It also became quite clear how interrelated the elements are to the story. It is difficult to discuss what should happen in a game without knowing where it happens or to whom it is happening. We intended to have a strict time schedule determined by the group as to how long a discussion of a single element should last, but the brainstorming soon made it obvious that strict division of elements would not accomplish our goals. We dropped the schedule, let the ideas flow, and still managed to accomplish our objectives.

Initial discussion of the protagonist (player character or PC) favored making the player take on the role of a young (18-year-old) female, which would create some built-in conflicts in our society, but the group eventually decided on allowing the player choose the PC’s sex.

They then came up with a list of characters. A number of potential antagonists and friends were suggested. Most popular was the Televangelist. The consensus eventually settled on the game scenario occurring around the year 2000 over a 5-year period, in a small town in Middle America, near a large city.

Once the theme, setting, and main character had been established, determining the mood was easy. Silliness was voted out quickly, but the group wanted some humor, and settled on making the game satirical. The eventual decision was to mix social satire and horror with a little bit of sex and some seriousness in the form of real consequences to the PC’s actions. It was considered crucial that the player be able to alter the PC’s relationships with various NPC’s.

When the plot and general climaxes were discussed, we briefly discussed what would make this a game instead of a story. Next time we run this, we will stress game play more.

It might be noted that since we didn’t have the restriction that the game be either marketable or profitable, what we came up with was truly an original product. It would probably be the first computer game to be banned by all fundamentalist churches. It is also possible that exorcisms would be held on the computers that played the game, not to mention the players.

Almost everyone who participated in the discussion went away enthusiastic. We really enjoyed the interaction, and plan to try the workshop again next year.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________A Review of deBabelizer

Aaron Urbina

(Editor’s Note: I’ve never done a review in the pages of the Journal, but Aaron has been so enthusiastic about this product that I decided to make an exception.)

While most of us computer types look forward to the day when there will be one very powerful standard computer, there’s no denying that these days, to make ends meet, you need to support as many platforms as possible. A lot has been done to further this noble cause, especially in the field of computer languages — most machines support “C”, for example. Graphics standards across platforms, on the other hand, have been neglected. Consequently, most of the work done by graphic artists on one machine has to be re-edited to work on others. This is a painstaking, boring, and time-consuming task. Now Equilibrium, Inc, has addressed this problem with deBabelizer™. This product is a leap forward in graphics conversion and manipulation technology.

The deBabelizer has a whole slew of features, including: color adjustment, grayscale conversion, Macintizing palette, color reduction, palette remapping, color duplicate removal, palette sorting, field interpolation (for digitized pictures), high quality scaling, pixel translation, background removal, and batch processing with script creation. Using the program is straightforward and quite clear, especially with the extensive and easily accessible on-line help built into it.

The program’s value lies in the enormous amount of time it saves. Its batch processing feature allows you to convert many picture files of any supported input format to any supported output format (i.e. Mac, IBM, or Apple II to Sun) in one run, freeing you up for less tedious tasks. Moreover, any of the other features may be included in the conversion process. For example, while converting, the image may also be scaled, the palette equalized, and the background removed. This minimizes the time it takes to edit each picture.

DeBabelizer™ also has a matrix cell animator (matrix cells are horizontal rows of equal size frames contained in one image file). Although primitive, it is quite useful for small scale animation; we used it to test digitized sequences. Once animation testing is completed, the slice images feature allows automatic saving of each cell. Speaking of animation, the Super Palette™ feature is a powerful animation tool that creates the best color palette for a series of images that have different palettes.

DeBabelizer™ comes in two consumer versions: deBabelizer™ “lite” which will only do file conversion, and deBabelizer™ “professional” which, along with conversions, also has all of the features described above and more. Both are due to hit the market later this year. Equilibrium is also willing to do OEM licenses, letting interested customers include deBabelizer code modules in their products.

If you are doing any type of graphics conversion from one machine to another I whole-heartedly recommend the deBabelizer™. It cut my re-editing time by 40% and was so easy to use that I never needed a manual. Interested parties should contact Frank Colin at Equilibrium, 914 Mission Avenue, 2nd floor, San Rafael, CA 94901 (415) 457-6333. a

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________“The Wonderful Power of Storytelling”

Bruce Sterling

(This is the speech that Bruce Sterling gave at the 1991 Computer Game Developers’ Conference)

Copyright © 1990 Bruce Sterling

Thank you very much for that introduction. I’d like to thank the conference committee for their hospitality and kindness – all the cola you can drink – and mind you those were genuine twinkies too, none of those newfangled “Twinkies Lite” we’ve been seeing too much of lately.

So anyway my name is Bruce Sterling and I’m a science fiction writer from Austin Texas, and I’m here to deliver my speech now, which I like to call “The Wonderful Power of Storytelling.” I like to call it that, because I plan to make brutal fun of that whole idea . . . In fact I plan to flame on just any moment now, I plan to cut loose, I plan to wound and scald tonight . . . . Because why not, right? I mean, we’re all adults, we’re all professionals here. . . I mean, professionals in totally different arts, but you know, I can sense a certain simpatico vibe . . . .

Actually tonight I feel like a mosasaur talking to dolphins . . . . We have a lot in common: we both swim, we both have big sharp teeth, we both eat fish . . . You look like a broadminded crowd, so I’m sure you won’t mind that I’m basically, like, reptilian . . . .

So anyway, you’re probably wondering why I’m, here tonight, some hopeless dipshit literary author . . . and when am I going to get started on the virtues and merits of the prose medium and its goddamned wonderful storytelling. I mean, what else can I talk about? What the hell do I know about game design? I don’t even know that the most lucrative target machine today is an IBM PC clone with a 16 bit 8088 running at 5 MHZ. If you start talking about depth of play versus presentation, I’m just gonna to stare at you with blank incomprehension . . . .

I’ll tell you straight out why I’m here tonight. Why should I even try to hide the sordid truth from a crowd this perspicacious . . . . You see, six months ago I was in Austria at this Electronic Arts Festival, which was a situation almost as unlikely as this one, and my wife Nancy and I are sitting there with William Gibson and Deb Gibson feeling very cool and rather jetlagged and crispy around the edges, and in walks this woman. Out of nowhere. Like J. Random Attractive Redhead, right. And she sits down with her coffeecup right at our table. And we peer at each other’s name badges, right, like, who is this person. And her name is Brenda Laurel.

So what do I say? I say to this total stranger, I say, “Hey. Are you the Brenda Laurel who did that book on the art of the computer-human interface? You are? Wow, I loved that book.” And yes – that’s why I’m here as your guest speaker tonight, ladies and gentleman. It’s because I can think fast on my feet. It’s because I’m the kind of author who likes to hang out in Adolf Hitler’s home town with the High Priestess of Weird.

So ladies and gentlemen, unfortunately I can’t successfully pretend that I know much about your profession. I mean actually I do know a few things about your profession . . . . For instance, I was on the far side of the Great Crash of 1984. I was one of the civilian crashees, meaning that was about when I gave up twitch games. That was when I gave up my Atari 800. As to why my Atari 800 became a boat-anchor I’m still not sure. . . . It was quite mysterious when it happened, it was inexplicable, kind of like the passing of a pestilence or the waning of the moon. If I understood this phenomenon I think I would really have my teeth set into something profound and vitally interesting. . . Like, my Atari still works today, I still own it. Why don’t I get it out of its box and fire up a few cartridges? Nothing physical preventing me. Just some subtle but intense sense of revulsion. Almost like a Sartrean nausea. Why this should be attached to a piece of computer hardware is difficult to say.

My favorite games nowadays are Sim City, Sim Earth and Hidden Agenda . . . I had Balance of the Planet on my hard disk, but I was so stricken with guilt by the digitized photo of the author and his spouse that I deleted the game, long before I could figure out how to keep everybody on the Earth from starving. . . . Including myself and the author . . . .

I’m especially fond of Sim Earth. Sim Earth is like a goldfish bowl. I also have the actual virtual goldfish bowl in the After Dark Macintosh screen saver, but its charms waned for me, possibly because the fish don’t drive one another into extinction. I theorize that this has something to do with a breakdown of the old dichotomy of twitch games versus adventure, you know, arcade zombie versus Mensa pinhead . . .

I can dimly see a kind of transcendence in electronic entertainment coming with things like Sim Earth, they seem like a foreshadowing of what Alvin Toffler called the “intelligent environ-ment” . . . Not “games” in a classic sense, but things that are just going on in the background somewhere, in an attractive and elegant fashion, kind of like a pet cat . . . I think this kind of digital toy might really go somewhere interesting.

What computer entertainment lacks most I think is a sense of mystery. It’s too left-brain . . . . I think there might be real promise in game designs that offer less of a sense of nitpicking mastery and control, and more of a sense of sleaziness and bluesiness and smokiness. Not neat tinkertoy puzzles to be decoded, not “treasure-hunts for assets,” but creations with some deeper sense of genuine artistic mystery.

I don’t know if you’ve seen the work of a guy called William Latham. . . . I got his work on a demo reel from Media Magic. I never buy movies on video, but I really live for raw computer-graphic demos reels. This William Latham is a heavy dude. . . His tech isn’t that impressive, he’s got some kind of fairly crude IBM mainframe cad-cam program in Winchester England. . . . That thing that’s most immediately striking about Latham’s computer artworks – ghost sculptures he calls them – is that the guy really possesses a sense of taste. Fractal art tends to be quite garish. Latham’s stuff is very fractally and organic, it’s utterly weird, but at the same time it’s very accomplished and subtle. There’s a quality of ecstasy and dread to it. . . there’s a sense of genuine enchantment there. A lot of computer games are stuffed to the gunwales with enchanters and wizards and so-called magic, but that kind of sci-fi cod mysticism seems very dime-store stuff by comparison with Latham.

I like to imagine the future of computer games as being something like the Steve Jackson Games bust by the Secret Service, only in this case what they were busting wouldn’t have been a mistake, it would have been something actually quite seriously inexplicable and possibly even a genuine cultural threat. . . . Something of the sort may come from virtual reality. I rather imagine something like an LSD backlash occurring there; something along the lines of: “Hey we have something here that can really seriously boost your imagination!” “Well, Mr. Developer, I’m afraid we here in the Food Drug and Software Administration don’t really approve of that.” That could happen. I think there are some visionary computer police around who are seriously interested in that prospect, they see it as a very promising growing market for law enforcement, it’s kind of their version of a golden vaporware.

l now want to talk some about the differences between your art and my art. My art, science fiction writing, is pretty new as literary arts go, but it labors under the curse of three thousand years of literacy. In some weird sense I’m in direct competition with Homer and Euripides. I mean, these guys aren’t in the SFWA, but their product is still taking up valuable rack-space. You guys on the other hand get to reinvent everything every time a new platform takes over the field. This is your advantage and your glory. This is also your curse. It’s a terrible kind of curse really.

This is a lesson about cultural expression nowadays that has applications to everybody. This is part of living in the Information Society. Here we are in the 90s, we have these tremendous information-handling, information-producing technologies. We think it’s really great that we can have groovy unleashed access to all these different kinds of data, we can buy computer-games, records, music, art. . . . A lot of our art aspires to the condition of software, our art today wants to be digital. . . But our riches of information are in some deep and perverse sense a terrible burden to us. They’re like a cognitive load. As a digitized information-rich culture nowadays, we have to artificially invent ways to forget stuff. I think this is the real explanation for the triumph of compact disks.

Compact disks aren’t really all that much better than vinyl records. What they make up in fidelity they lose in groovy cover art. What they gain in playability they lose in presentation. The real advantage of CDs is that they allow you to forget all your vinyl records. You think you love this record collection that you’ve amassed over the years. But really the sheer choice, the volume, the load of memory there is secretly weighing you down. You’re never going to play those Alice Cooper albums again, but you can’t just throw them away, because you’re a culture nut.

But if you buy a CD player you can bundle up all those records and put them in attic boxes without so much guilt. You can pretend that you’ve stepped up a level, that now you’re even more intensely into music than you ever were; but on a practical level what you’re really doing is weeding this junk out of your life. By dumping the platform you dump everything attached to the platform and my god what a blessed secret relief. What a relief not to remember it, not to think about it, not to have to take up disk-space in your head.

Computer games are especially vulnerable to this because they live and breathe through the platform. But something rather similar is happening today to fiction as well . . . . What you see in science fiction nowadays is an amazing tonnage of product that is shuffled through the racks faster and faster. . . . If a science fiction paperback stays available for six weeks, it’s a miracle. Gross sales are up, but individual sales are off . . . Science fiction didn’t even used to be published in book form, when a science fiction book came out, it would be in an edition of maybe five hundred copies, and these weirdo Golden Age SF fans would cling on to every copy as if it were made of platinum. . . . But now they come out and they are made to vanish as soon as possible. In fact to a great extent they’re designed by their lame hack authors to vanish as soon as possible. They’re cliches because cliches are less of a cognitive load. You can write a whole trilogy instead, bet you can’t eat just one. . . Nevertheless they’re still objects in the medium of print. They still have the cultural properties of print.

Culturally speaking they’re capable of lasting a long time because they can be replicated faithfully in new editions that have all the same properties as the old ones. Books are independent of the machineries of book production, the platforms of publishing. Books don’t lose anything by being reprinted by a new machine, books are stubborn, they remain the same work of art, they carry the same cultural aura. Books are hard to kill. Moby Dick for instance bombed when it came out, it wasn’t until the 1920s that Moby Dick was proclaimed a masterpiece, and then it got printed in millions. Emily Dickinson didn’t even publish books, she just wrote these demented little poems with a quill pen and hid them in her desk, but they still fought their way into the world, and lasted on and on and on. It’s damned hard to get rid of Emily Dickinson, she hangs on like a tick in a dog’s ear. And everybody who writes from then on in some sense has to measure up to this woman. In the art of book-writing the classics are still living competition, they tend to elevate the entire art-form by their persistent presence.

I’ve noticed though that computer game designers don’t look much to the past. All their idealized classics tend to be in reverse, they’re projected into the future. When you’re a game designer and you’re waxing very creative and arty, you tend to measure your work by stuff that doesn’t exist yet. Like now we only have floppies, but wait till we get CD-ROM. Like now we can’t have compelling lifelike artificial characters in the game, but wait till we get AI. Like now we waste time porting games between platforms, but wait till there’s just one standard. Like now we’re just starting with huge multiplayer games, but wait till the modem networks are a happening thing. And I – as a game designer artiste – it’s my solemn duty to carry us that much farther forward toward the beckoning grail. . . .

For a novelist like myself this is a completely alien paradigm. I can see that it’s very seductive, but at the same time I can’t help but see that the ground is crumbling under your feet. Every time a platform vanishes it’s like a little cultural apocalypse. And I can imagine a time when all the current platforms might vanish, and then what the hell becomes of your entire mode of expression? Alan Kay – he’s a heavy guy, Alan Kay – he says that computers may tend to shrink and vanish into the environment, into the walls and into clothing. . . . Sounds pretty good. . . . But this also means that all the joysticks vanish, all the keyboards, all the repetitive strain injuries.

I’m sure you could play some kind of computer game with very intelligent, very small, invisible computers. . . . You could have some entertaining way to play with them, or more likely they would have some entertainment way to play with you. But then imagine yourself growing up in that world, being born in that world. You could even be a computer game designer in that world, but how would you study the work of your predecessors? How would you physically access and experience the work of your predecessors? There’s a razor-sharp cutting edge in this art-form, but what happened to all the stuff that got sculpted?

As I was saying, I don’t think it’s any accident that this is happening. . . . I don’t think that as a culture today we’re very interested in tradition or continuity. No, we’re a lot more interested in being a New Age and a revolutionary epoch, we long to reinvent ourselves every morning before breakfast and never grow old. We have to run really fast to stay in the same place. We’ve become used to running, if we sit still for a while it makes us feel rather stale and panicky. We’d miss those sixty-hour work weeks.

And much the same thing is happening to books today too. . . . Not just technically, but ideologically. I don’t know it you’re familiar at all with literary theory nowadays, with terms like deconstructionism, postmodernism. . . . Don’t worry, I won’t talk very long about this. . . . It can make you go nuts, that stuff, and I don’t really recommend it, it’s one of those fields of study where it’s sometimes wise to treasure your ignorance. . . . But the thing about the new literary theory that’s remarkable, is that it makes a really violent break with the past. . . . These guys don’t take the books of the past on their own cultural terms. When you’re deconstructing a book it’s like you’re psychoanalyzing it, you’re not studying it for what it says, you’re studying it for the assumptions it makes and the cultural reasons for its assemblage. . . . What this essentially means is that you’re not letting it touch you, you’re very careful not to let it get its message through or affect you deeply or emotionally in any way. You’re in a position of complete psychological and technical superiority to the book and its author. . . This is a way for modern literateurs to handle this vast legacy of the past without actually getting any of the sticky stuff on you. It’s like it’s dead. It’s like the next best thing to not having literature at all. For some reason this reels really good to people nowadays.

But even that isn’t enough, you know. . . . There’s talk nowadays in publishing circles about a new device for books, called a ReadMan. Like a Walkman only you carry it in your hands like this. . . . Has a very nice little graphics screen, theoretically, a high-definition thing, very legible. . . . And you play your books on it. . . . You buy the book as a floppy and you stick it in. . . And just think, wow you can even have graphics with your book. . . you can have music, you can have a soundtrack. . . . Narration. . . . Animated illustrations. . . Multimedia. . . it can even be interactive. . . . It’s the New Hollywood for Publisher’s Row, and at last books can aspire to the exalted condition of movies and cartoons and TV and computer games. . . . And just think when the ReadMan goes obsolete, all the product that was written for it will be blessedly gone forever!!! Erased from the memory of mankind!

Now I’m the farthest thing from a Luddite ladies and gentlemen, but when I contemplate this particular technical marvel my author’s blood runs cold. . . It’s really hard for books to compete with other multisensory media, with modern electronic media, and this is supposed to be the panacea for withering literature, but from the marrow of my bones I say get that fucking little sarcophagus away from me. For God’s sake don’t put my books into the Thomas Edison kinetoscope. Don’t put me into the stereograph, don’t write me on the wax cylinder, don’t tie my words and my thoughts to the fate of a piece of hardware, because hardware is even more mortal than I am, and I’m a hell of a lot more mortal than I care to be. Mortality is one good reason why I’m writing books in the first place. For God’s sake don’t make me keep pace with the hardware, because I’m not really in the business of keeping pace, I’m really in the business of marketing place.

Okay. . . . Now I’ve sometimes heard it asked why computer game designers are deprived of the full artistic respect they deserve. God knows they work hard enough. They’re really talented too, and by any objective measure of intelligence they rank in the top percentiles. . . I’ve heard it said that maybe this problem has something to do with the size of the author’s name on the front of the game-box. Or it’s lone wolves versus teams, and somehow the proper allotment of fame gets lost in the muddle. One factor I don’t see mentioned much is the sheer lack of stability in your medium. A modern movie-maker could probably make a pretty good film with DW Griffith’s equipment, but you folks are dwelling in the very maelstrom of Permanent Technological Revolution. And that’s a really cool place, but man, it’s just not a good place to build monuments.

Okay. Now I live in the same world you live in, I hope I’ve demonstrated that I face a lot of the same problems you face. . . Believe me there are few things deader or more obsolescent than a science fiction novel that predicts the future when the future has passed it by. Science fiction is a pop medium and a very obsolescent medium. The fact that written science fiction is a prose medium gives us some advantages, but even science fiction has a hard time wrapping itself in the traditional mantle of literary excellence. . . we try to do this sometimes, but generally we have to be really drunk first. Still, if you want your work to survive (and some science fiction does survive, very successfully) then your work has to capture some quality that lasts. You have to capture something that people will search out over time, even though they have to fight their way upstream against the whole rushing current of obsolescence and innovation.

And I’ve come up with a strategy for attempting this. Maybe it’ll work – probably it won’t – but I wouldn’t be complaining so loudly if I didn’t have some kind of strategy, right? And I think that my strategy may have some relevance to game designers so I presume to offer it tonight.

This is the point at which your normal J. Random Author trots out the doctrine of the Wonderful Power of Storytelling. Yes, storytelling, the old myth around the campfire, blind Homer, universal Shakespeare, this is the art ladies and gentlemen that strikes to the eternal core of the human condition. . . This is high art and if you don’t have it you are dust in the wind. . . . I can’t tell you how many times I have heard this bullshit. . . This is known in my field as the “Me and My Pal Bill Shakespeare” argument. Since 1982 I have been at open war with people who promulgate this doctrine in science fiction and this is the primary reason why my colleagues in SF speak of me in fear and trembling as a big bad cyberpunk. . . This is the classic doctrine of Humanist SF.

This is what it sounds like when it’s translated into your jargon. Listen closely:

“Movies and plays get much of their power from the resonances between the structural layers. The congruence between the theme, plot, setting and character layouts generates emotional power. Computer games will never have a significant theme level because the outcome is variable. The lack of theme alone will limit the storytelling power of computer games.”

Hard to refute. Impossible to refute. Ladies and gentlemen to hell with the marvellous power of storytelling. If the audience for science fiction wanted storytelling, they wouldn’t read goddamned science fiction, they’d read Harpers and Redbook and Argosy. The pulp magazine (which is our genre’s primary example of a dead platform) used to carry all kinds of storytelling. Western stories. Sailor stories. Prizefighting stories. G-8 and his battle aces. Spicy Garage Tales. Aryan Atrocity Adventures. These things are dead. Stories didn’t save them. Stories won’t save us. Stories won’t save you.

This is not the route to follow. We’re not into science fiction because it’s good literature, we’re into it because it’s weird. Follow your weird, ladies and gentlemen. Forget trying to pass for normal. Follow your geekdom. Embrace your nerditude. In the immortal words of Lafcadio Hearn, a geek of incredible obscurity whose work is still in print after a hundred years, “woo the muse of the odd.” A good science fiction story is not a “good story” with a polite whiff of rocket fuel in it. A good science fiction story is something that knows it is science fiction and plunges through that and comes roaring out of the other side. Computer entertainment should not be more like movies, it shouldn’t be more like books, it should be more like computer entertainment, so much more like computer entertainment that it rips through the limits and is simply impossible to ignore!

I don’t think you can last by meeting the contemporary public taste, the taste from the last quarterly report. I don’t think you can last by following demographics and carefully meeting expectations. I don’t know many works of art that last that are condescending. I don’t know many works of art that last that are deliberately stupid. You may be a geek, you may have geek written all over you; you should aim to be one geek they’ll never forget. Don’t aim to be civilized. Don’t hope that straight people will keep you on as some kind of pet. To hell with them; they put you here. You should fully realize what society has made of you and take a terrible revenge. Get weird. Get way weird. Get dangerously weird. Get sophisticatedly, thoroughly weird and don’t do it halfway, put every ounce of horsepower you have behind it. Have the artistic courage to recognize your own significance in culture!

Okay. Those of you into SF may recognize the classic rhetoric of cyberpunk here. Alienated punks, picking up computers, menacing society. . . .That’s the cliched press story, but they miss the best half. Punk into cyber is interesting, but cyber into punk is way dread. I’m into technical people who attack pop culture. I’m into techies gone dingo, techies gone rogue – not street punks picking up any glittery junk that happens to be within their reach – but disciplined people, intelligent people, people with some technical skills and some rational thought, who can break out of the arid prison that this society sets for its engineers. People who are, and I quote, “dismayed by nearly every aspect of the world situation and aware on some nightmare level that the solutions to our problems will not come from the breed of dimwitted ad-men that we know as politicians.” Thanks, Brenda!

That still smells like hope to me. . . .

You don’t get there by acculturating. Don’t become a well-rounded person. Well rounded people are smooth and dull. Become a thoroughly spiky person. Grow spikes from every angle. Stick in their throats like a pufferfish. If you want to woo the muse of the odd, don’t read Shakespeare. Read Webster’s revenge plays. Don’t read Homer and Aristotle. Read Herodotus where he’s off talking about Egyptian women having public sex with goats. If you want to read about myth don’t read Joseph Campbell, read about convulsive religion, read about voodoo and the Millerites and the Munster Anapabtists. There are hundreds of years of extremities, there are vast legacies of mutants. There have always been geeks. There will always be geeks. Become the apotheosis of geek. Learn who your spiritual ancestors were. You didn’t come from nowhere. There are reasons why you’re here. Learn those reasons. Learn about the stuff that was buried because it was too experimental or embarrassing or inexplicable or uncomfortable or dangerous.

And when it comes to studying art, well, study it, but study it to your own purposes. If you’re obsessively weird enough to be a good weird artist, you generally face a basic problem. The basic problem with weird art is not the height of the ceiling above it, it’s the pitfalls under its feet. The worst problem is the blundering, the solecisms, the naivete of the poorly socialized, the rotten spots that you skid over because you’re too freaked out and not paying proper attention. You may not need much characterization in computer entertainment. Delineating character may not be the point of your work. That’s no excuse for making lame characters that are actively bad. You may not need a strong, supple, thoroughly work-out storyline. That doesn’t mean that you can get away with a stupid plot made of chickenwire and spit. Get a full repertoire of tools. Just make sure you use those tools to the proper end. Aim for the heights of professionalism. Just make sure you’re a professional game designer.

You can get a hell of a lot done in a popular medium just by knocking it off with the bullshit. Popular media always reek of bullshit, they reek of carelessness and self-taught clumsiness and charlatanry. To live outside the aesthetic laws you must be honest. Know what you’re doing; don’t settle for the way it looks just cause everybody’s used to it. If you’ve got a palette of 2 million colors, then don’t settle for designs that look like a cheap four-color comic book. If you’re gonna do graphic design, then learn what good graphic design looks like; don’t screw around in amateur fashion out of sheer blithe ignorance. If you write a manual, don’t write a semiliterate manual with bad grammar and misspellings. If you want to be taken seriously by your fellows and by the populace at large, then don’t give people any excuse to dismiss you. Don’t be your own worst enemy. Don’t put yourself down.

I have my own prejudices and probably more than my share, but I still think these are pretty good principles. There’s nothing magic about ‘em. They certainly don’t guarantee success, but then there’s “success” and then there’s success. Working seriously, improving your taste and perception and understanding, knowing what you are and where you came from, not only improves your work in the present, but gives you a chance of influencing the future and links you to the best work of the past. It gives you a place to take a solid stand. I try to live up to these principles; I can’t say I’ve mastered them, but they’ve certainly gotten me into some interesting places, and among some very interesting company. Like the people here tonight.

I’m not really here by any accident. I’m here because I’m paying attention. I’m here because I know you’re significant. I’m here because I know you’re important. It was a privilege to be here. Thanks very much for having me, and showing me what you do.

That’s all I have to say to you tonight. Thanks very much for listening.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________An Approach to Plotting Interactive Fiction Part II

Scott Jarol

Copyright © 1990 Scott Jarol

Rube Goldberg Variations

In parts I and II of this series we reviewed two approaches to plot analysis for dramatic fiction: Bernard Grebanier’s “Proposition,” which focuses on theatrical scripts; and Syd Field’s “Paradigm,” a tool with which to develop movie plots.

Obviously, plotting in interactive fiction is going to differ from plotting in prose, theatrical or screen narrative. For one thing, the author has to work out many more consequences, since the Protagonist is no longer bound to pursue a single course of events. But the goal of all fiction is to stimulate in the reader/audience an empathetic response to the main character or characters. The degree or quality of resonance in that empathy will determine the extent to which the reader/audience identifies with the protagonist. The more dissonant that resonance, the more challenging the story becomes. The most challenging stories ask us to assume a psyche which runs contrary to our nature, seducing us into vicarious acts we would otherwise shun.

In interactive fiction the plot connections are harder to make because we can’t as carefully dole out the story to control the suspense. We could imagine an interactive story as a collection of events, all of which must take place for the story to reach its conclusion. A story with more than one ending would have more potential events, and each outcome would be the result of a particular assortment of events.

Some things though, must happen in order or they just won’t make sense. If you find the terrorists before they hijack the plane, there isn’t much left to tell. A story cannot move forward, and certainly cannot generate suspense, unless we can control its sequence.

The simplest way to plot an interactive story would be to force the Plot Points and Climax by structuring the story so that you can wait for the Protagonist to stumble into a series of traps. That way the Protagonist would tend to see himself as the cause of the action (the “agent”) rather than feeling manipulated, even though he couldn’t do anything to alter its course. This would result in a tightly controlled story, with only one ending.

Although this technique works fine for print, film and theater, an interactive story with this structure would more likely frustrate than amuse the player.

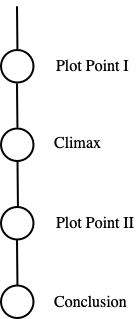

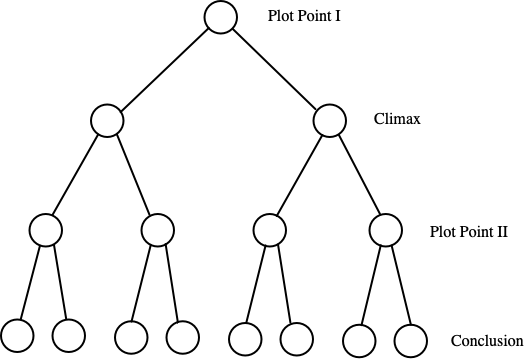

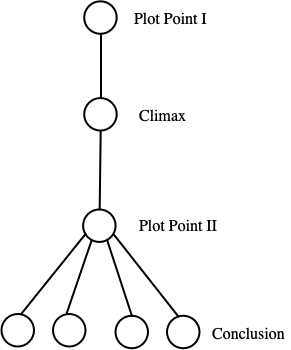

An alternative would be to branch the story at each plot point. This can easily get out of hand. For example, let’s say your story is built around three key decisions and each of those yields only two choices. This will produce eight possible outcomes:

A moderate approach would be to split the difference and permit three to five possible conclusions. We could reduce these choices to a formula.

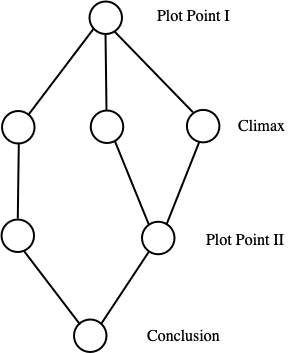

Plot Point I is the least alterable. It determines what the story is about (Grebanier’s Proposition Item 2). If you allow variable consequences to the first Plot Point you’re actually starting more than one story/game. Restricting yourself to one result for Plot Point I doesn’t mean you can only have one path to this critical milestone, it just means that no matter how he or she gets there, the Protagonist has to always end up in the same predicament.

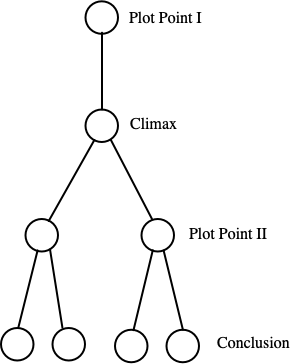

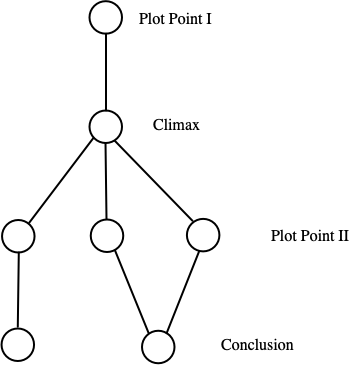

If we restrict Plot Point I this way, that leaves only two story points where we have to offer choices with radically different consequences, the Climax and Plot Point II. If we limit the choices to two per story node, then we have only four endings to contend with:

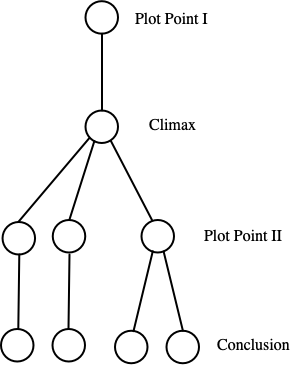

You could also use non-binary splits to produce simple variations of this pattern:

This last version would probably be too obvious to the Player. The Climax should be pivotal to the story, so the first and second structures are more likely than the third to yield an interesting story.

Another way to control branching is to reconnect some paths. A pattern of this form is called a “reticulate network:”

Reticulate paths at least create an illusion of choice, varied enough for anyone who plays the game only once or twice.

The inevitable truth is that you have to limit your player’s choices. To make the interactive fiction interesting however, you have to disguise the boundaries you’ve imposed. If the player begins to feel like a laboratory rat in a maze, he’ll quit. So how do you resolve this paradox?

Interactive fiction offers a lot of inherent freedom. The setting itself, despite the fact that it is usually called a maze, affords the player great apparent freedom. If it were truly a maze, the player would discover only one path through it. But when the setting is more open, with many redundant paths, the player will feel unhampered. Geographical freedom will tend to beguile the player, which can go a long way toward camouflaging a manipulative story. As long as the Player Protagonist gets to make many less critical choices in the course of the game, he won’t easily realize that he is being guided in the larger scope of the plot. However, while you need not implement the universe, you still do need to build enough diversity into the plot itself so the Player can experience the consequences of her own actions.

Just because a dramatic story must pivot on a series of Plot Points, doesn’t mean that the Player has to stop at each of these points and explicitly choose an option. The selection of these Master Plot Paths would be internal, based on criteria that had been met throughout the preceding story. One set of actions by the Player in the first act would cause the story to follow a particular direction at Plot Point I, another set would cause a different turn. By building in criteria that are numerous and varied enough, the Player will find it difficult to second guess your program.

Once you have disguised the plot’s mechanisms you need to develop a way to gently shepherd the Player through them. To adapt a story like Back to the Future into an interactive story, you would have to set traps. In a way, that’s what happens in the original story. The outcome is determined by how the hero responds to relentless (but related) challenges. If Marty doesn’t follow George to Lorraine’s house, then let him run into George and Lorraine somewhere else. After Marty’s grandfather-to-be hits him with his car, Lorraine could jump out of the car and render aid in the street. You need to corral the Player into the story; force him to participate. If he evades all your tactics, bore him — then send Biff after him.

For you, as a member of the movie audience, the first Plot Point of Back to the Future raises certain expectations. When Marty travels back to 1955, you assume (perhaps only unconsciously), that by the end of the story he will return to his own time. Often, once a story begins, we know how it will end; what interests us is how the hero will get there. The presence of stable Plot Points needn’t weigh down your story.

Remember, a story is about an event, not a subject, philosophy, idea, race, nor any other abstract entity. The place of an idea in a story is to motivate the characters to perform the Actions from which the plot is built. Regardless of your story’s theme, always state your plot as a summary of who does what to whom. The Plot is not what happens to the characters, it’s what the characters do.

Chinese Boxes

There is another dimension to plotting, or rather another degree of magnification: all the stuff that happens between the three major plot points (I, II, and the Climax). The texture of a story, its moment to moment quality, depends on the richness and diversity of its sub-plots.

Everything that happens in a dramatic story should move the action forward, either by introducing or vanquishing an obstacle. Each scene is a miniature plot in itself, with its own beginning, middle, and end. But still each scene must fortify the momentum of the main plot.

As you probe the anatomy of fiction you begin to discover that depth is more than sedimentary, it is the result of containment — what programmers call nesting. Dramatic fiction is crafted in the same fashion, and the greater the author’s attention to the details of each recursion, the richer the story.

You must also look at the plot from the perspective of each character. The proportions of the acts may vary, but each of the prominent characters must experience his or her own dilemma. Darth Vader’s first plot point occurs when he confronts his old mentor, Obi-Wan Kenobi. His problem is to discover and capture the younger Jedi Knight, Luke Skywalker, before he can destroy the Death Star.

Can a Story be Played?

Interactivity adds a new expressive language to the craft of storytelling. Just as line and light are languages to the visual artist, and motion is to a filmmaker, choices are a language for the author of interactive fiction. The richness of creative choices in any medium determine how deeply textured the products of that medium may become. Now the artist can share the process of making choices, subtly disguising her ideas with a new and potent form of rhetoric. Each time the Player changes direction, retrieves an object, or hands an object to another character, he is making a choice. The goal of all rhetoric, whether factual or fictional, is to induce the reader to choose your opinion over all others. A successful salesman doesn’t sell, he helps the purchaser discover his own desire to buy.

The challenge of telling a convincing and rewarding story is assembling the elements from which a story emerges. An author creates characters, places them within settings and circumstances, then documents their behavior. When a writer claims that a story has “written itself” (a rare experience for all but the most gifted), he or she means that the elements of the story contained a natural tension which drove the narrative. Once you understand the mechanics that enable a story to happen, you can assemble them, then step aside. From an understanding of conventional narrative techniques we can develop methods by which to facilitate rather than tell stories.

In a dramatic story, plot and character define each other. The plot IS what the main character DOES; and all we know about a character is what we infer from his or her actions. The author of an interactive story must create a world in which the main character is implied, a phantom waiting to inhabit, and to be inhabited by the Player. The personality of the main character is determined by the interplay between the Player’s own personality and a plot so compelling and so subtly directive, that the Player assumes the “Virtual Personality” (or one of the personalities) intended by the author.

Next time, we’ll look more closely at how a story like Back to the Future could be adapted for interactivity — without towing along the Player like a Buick in an automatic carwash.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________