October 18th, 2018

Your eyes don’t do what you think they do. They are not at all like cameras — they are far more sophisticaed than that. If you can understand how your visual system works, you can see how to extend it to see things that other people can’t see.

Levels of perception

First off, your eyes don’t do much of the work of vision; they’re just the starting point. Most of what you “see” is actually created deep inside your brain. It’s a complicated and brilliant system that accomplishes an enormous amount with a minimum of brain matter and energy. In order to understand this system, you must think of it in terms of levels of operation. Your eye itself is at the very bottom level; above it is an ascending series of layers that process the raw data from your eyes in increasingly sophisticated ways.

Lowest Layer: the retina

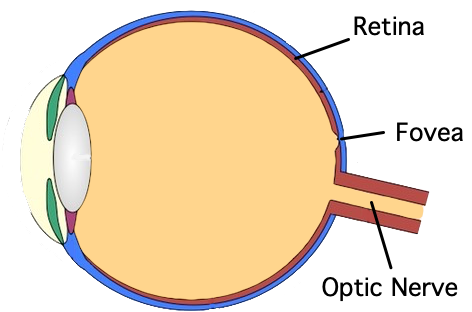

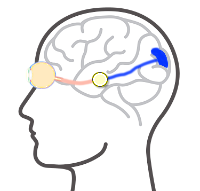

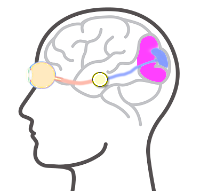

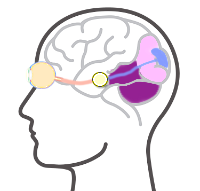

Everything starts at the retina, the focal plane of the eye’s lens. Here’s a schematic diagram showing the three components important to this discussion:

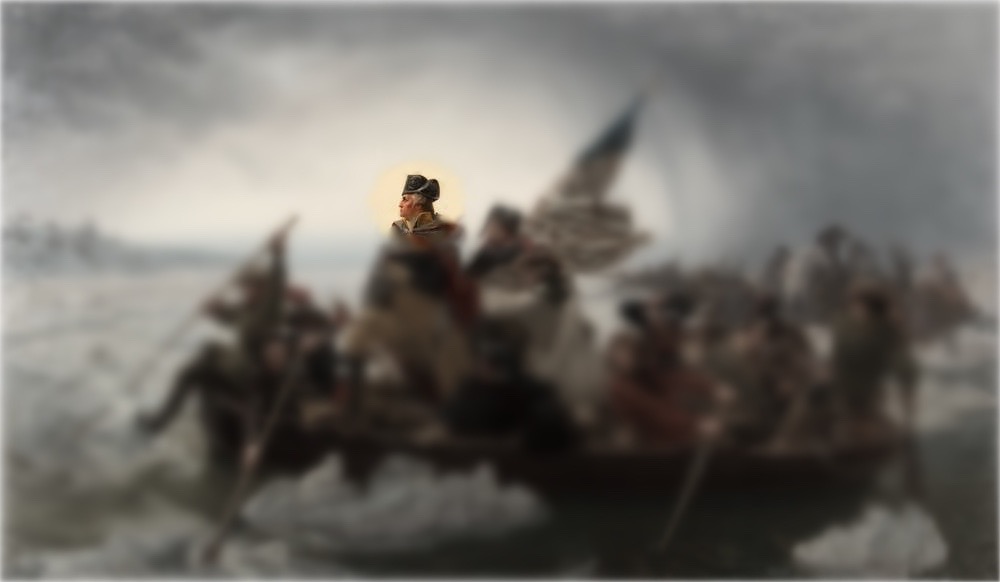

The visual information is collected by the retina, which includes the fovea, and sent down the optic nerve. The retina and the fovea perform radically different functions. Suppose that you were looking at the classic painting of Washington crossing the Delaware River:

This is what your eye would actually see at any given instant in time:

That’s because most of the retina sees only a little color and it doesn’t have much resolution. Only your fovea, the tiny spot in the center of the optical axis of your eye, sees anything with any clarity. So in this snapshot of the eye’s vision, only George Washington’s head is clearly visible.

So think of the lowest level of vision as consisting of two teams. The first team is the Fovea Team: think of it as the high-precision team using a telescope to closely examine what’s out there. The Fovea Team is your primary source of vision.

The other team is composed of the retina; it doesn’t see anything very clearly. Its job is not to provide any detail. Instead, its job is to scan a wide area for anything that’s happening. Think of this team as “The Sentinels”. They are constantly viewing the big picture. If something moves or changes, they send the alert up the chain of command that something is happening, and they say where that something is happening.

Second Level: the Controller

The controller tells the fovea team where to point their telescope. If it gets an alert from the Sentinel Team that something is moving, it will direct the fovea team to point their telescope (that is, move the eye) at the moving object. But this doesn’t happen often. Most of the time, the Controller is telling the Fovea Team to scan around the image, picking up more details.

You probably don’t realize just how fast your Fovea Team is. That eyeball of yours is darting all over the place, taking in all sorts of fine detail at a breathtaking speed. You’re not even aware of all that activity any more than you’re aware of the blood circulating in your body or the kidneys doing their job of cleaning your blood. So the little spot of clarity that you see in the picture above is actually darting all over the painting, picking up all the little details with lightning speed. Each movement is called a saccade; the eye can rotate 90º in a tenth of a second. The Controller usually keeps saccade movements small and quick. The Controller handles all those orders to move the eyeball.

Third Level: the Director

The Controller doesn’t do much more than move the eyeballs around. The decisions about where to move the eyeballs are made by The Director. The Controller doesn’t just sweep the telescope back and forth around the image; the Director provides the intelligence to scan the image in the most efficient manner. In this case, the Director would probably order the Controller to sweep down and to the left as part of an effort to figure out what this big dark object in the foreground is:

The Director would continue moving around the image, picking out the most important details. First it would figure out the image of the boat in the foreground. Then it would move to the boat in the background, then the ice. It wouldn’t bother with the sky until everything else had been figured out. Here’s a recording of the saccades ordered by the Director in scanning the image of a face:

Thus, the Director produces something like a movie, a sequence of little circular images that all add up to the overall image. But somebody has to assemble all those images into the overall image. That job goes to the Editor.

Fourth Level: the Editor

The Editor has the memory to hold all of those fragmentary images. It puts each little piece up onto its canvas, assembling it all into a coherent image. You still don’t “see” this image; a lot more work has to be done before the visual system will “show” it to you. The Editor is always in a hurry, working to put together the entire image as quickly as possible. To do this, the Editor has a number of very smart assistants who automatically fill in blank spots so that the Editor doesn’t have to actually get that visual data.

There’s an entire department of specialist assistants ready to fill in details for the Editor. One of the most talented of these assistants is the Facial Recognition Assistant. This lady knows everything there is to know about faces: how they look from different angles, in different lighting conditions, and with different kinds of people. She knows all about beards and ears and noses and eyes and hats and hair and uses all that knowledge to fill in the details of each and every face in that painting. The Editor didn’t need to have the Fovea Team fill in the precise details of each and every face; the Facial Recognition Assistant took over and filled in the details as soon as she had enough information to figure out exactly what each face should look like. You can see how she requires only a few key saccades to figure out the details of the face above.

This is really important! Your visual system does this kind of thing all the time, filling in details that may not actually be there. It is especially active when confronted with vague or fuzzy images. For example, do you remember the famous “face on Mars”?

This picture was taken by one of the first Mars probes, and it excited all sorts of interest. You can’t help but see a face! But you see a face only because the image is so blurry, and the lighting is just right. It turns out that, over the years, as we got better and better satellites going to Mars, our view of the “face” improved:

In the real world, though, you can’t wait 25 years to get better images. When your eyes see something, you need to know what it is RIGHT NOW, not later. So your visual system is equipped with an entire department of special assistants who are very good at filling in details. This is why we can look at clouds and see all sorts of things:

Fifth Level: the Analyst

There’s one more level of processing on the imagery, and it’s easily the most powerful. The Analyst interprets imagery in view of our expectations. It uses everything we know about the world to figure out what it is we’re looking at. Consider this photograph, for example:

What kind of trees do you see? You’ll immediately answer “conifers” or perhaps “pine trees” or “fir trees”. But honestly, can you actually see individual conifer trees? Of course not — but you recognize the visual context: a mountain with some snow, and you mentally fill in the rest of the image.

We do this kind of thing all the time: filling in the blanks in the scene based on our knowledge of the world. Indeed, a great deal of what we think we see is actually our own expectations placed onto the scene we see. This has formed the basis for many visual jokes:

Sixth Level: Beyond

This objective of this course is to take you to the next level of perception: to see not just what is, but what is happening. To see reality in a completely different way. But it requires the application of your mind at an even higher, more abstract level. Not many people can do it, and even fewer can apply the sixth level of perception to creative work.