A storyworld contains both Object elements (actors, props, and stages) and Process elements. The Object elements are manifested spatially: they are spatially variable but temporally static. Process elements are essentially temporal in nature.

Events

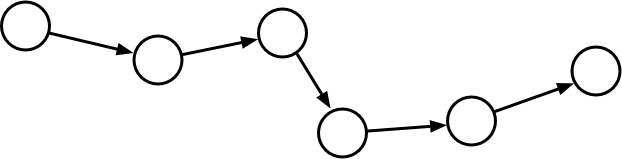

A story is a sequence of causally related events that together communicate some truth of the human condition:

Each of these circles represents an event, and the arrow shows the logical connection between events. The first circle might be “Once upon a time…” and the last circle might be “…and they lived happily ever after.”

Time in stories does not proceed smoothly. There is no ticking clock in stories. Games often use continuous time; this is a concept that game designers must throw overboard. Instead, they must perceive a story as a sequence of events that may be separated by long stretches of time.

In the classic movie Excalibur (1981), Uther Pendragon, king of England, makes peace with the Duke of Cornwall after years of fighting. They go to Cornwall’s castle to feast together. Cornwall has his wife Igraine dance for the diners. Igraine dances a blazing hot sexual dance; Uther is overwhelmed with passion for Igraine. Cornwall, realizing that things are getting out of hand, yells and Igraine suddenly stops, prostrating herself before Cornwall. The very next shot shows men driving a battering ram into the front gate of a castle. Huh? After just a moment’s pause, it’s easy to figure out the intervening circles in the story: Uther demanded sex with Igraine; Cornwall refused; Uther stormed out, gathered his army, and returned to lay siege to Cornwall’s castle. None of those details needed to be explained; the causal relationship between Uther’s lust and the attack on the castle was clear.

What is an event? What are its attributes? It just so happens that we already have a handy-dandy tool for describing events: the sentence. The whole point and purpose of every sentence is to describe an event, although there are different ‘moods’ to sentences indicating whether the event in question is in the past, in the future, feared, demanded, expected, etc.

Every sentence consists of at least one subject and one verb. Those are the absolute minimum constituents of every sentence. Sentences can have far more than these, of course; for example, this very sentence has two clauses with two subjects, two verbs, two conjunctions, some prepositional phrases, and some direct objects. How in the world can you use sentences in a computer to tell stories?

At this point the computer scientists will step in with all sorts of fascinating details, theories, models, and other academic paraphernalia that only a computer scientist with years of experience can understand. None of this will do you any good. Fortunately, I, who am not a computer scientist and couldn’t fool a freshman into thinking that I am, have a much more accessible (e.g., dumb) approach to sentences requiring some brutal simplifications. I’m going to do to sentences what LeatherFace does to people in “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre”.

Subject

The first simplification is the requirement that the subject of every sentence be an actor. After all, you can’t have rocks or turtles being subjects of sentences, can you? Well, you can, I suppose, as in “The rock fell on John’s head and smooshed it.” But there’s a simple solution to that problem, which turns out to be of great utility in many other situations: a new actor called “Fate”. Fate does a lot of things. For example: “Fate dropped the rock on John’s head and smooshed it.”

Fate plays a crucial role in almost all stories, but never gets any billing or credit; Fate doesn’t even get paid! For example, consider this classic scene, variations on which you’ve seen a million times:

The hero has chased the villain to his mountain castle and they begin to fight with their swords. The hero is obviously a better swordsman than the villain, but the villain keeps using dirty tricks like pulling things down on the hero. The villain retreats as they fight, leaving the castle and ascending to the highest crag of the mountain as the furious winds tear at their capes (heros and villains always wear capes) and the rain lashes at their faces. The villain slips and teeters on the edge of the cliff, and the hero magnanimously grabs his arm to save him from plummeting to his doom. The villain takes advantage of the hero’s gesture and knocks him down. Standing over the prostrate hero, the villain leers evilly at the hero as he laughingly raises his sword over his head to deliver the death blow, when

Fate strikes the villain with a bolt of lightning.

Do you think that bolt of lightning came out of nowhere? Do you think it was just a coincidence? Of course not! Fate made it happen. It HAD to happen! It’s a STORY!

That’s what Fate is for. He is the first actor in every story, and he’s the one who makes things happen. (Of course, if you want to build a feminist storyworld, you’re welcome to use a female Fate.)

The next component of a sentence is the verb. This is where things get REALLY complicated, so I’m ending this lesson right here. Take a deep breath, assume the lotus position, gather your wits, gird your loins, and eat your spinach before proceeding to the next lesson.