I put a lot of effort into making this storyworld as accurate as possible. I’m not going to compromise dramatic power to realism; drama comes first and foremost. But my bet is that people will find the underlying world intrinsically interesting, and that this will justify plowing through the long list of petty decisions that make up the substance of the story. One of my many mistakes with Storytron was thinking of story in terms of major dramatic turning points. Much of what makes a rich story are the many small decisions, each of which has minor dramatic significance, but which, taken together, make the full drama. I hope to make those many small decisions acceptable by embedding them in intrinsically interesting context.

One of the most important decisions is the overall population with which Arthur must deal. Estimates are that the population of Britain around 500 CE was between one and two million, and that the various invaders (Angles, Saxons, Jutes, etc) amounted to perhaps 100,000 people. If you’re asking how 100,000 invaders managed to conquer two million Britons, well, the answer to that is complicated. Remember, it took them about 300 years to overrun England, and they never took Wales. But my problem concerns the population in Arthur’s area. For dramatic reasons, I confine him to southwestern Britain (Cornwall, Devon, Somerset, Dorset, Wiltshire, and parts of Glouscestershire and Hampshire)

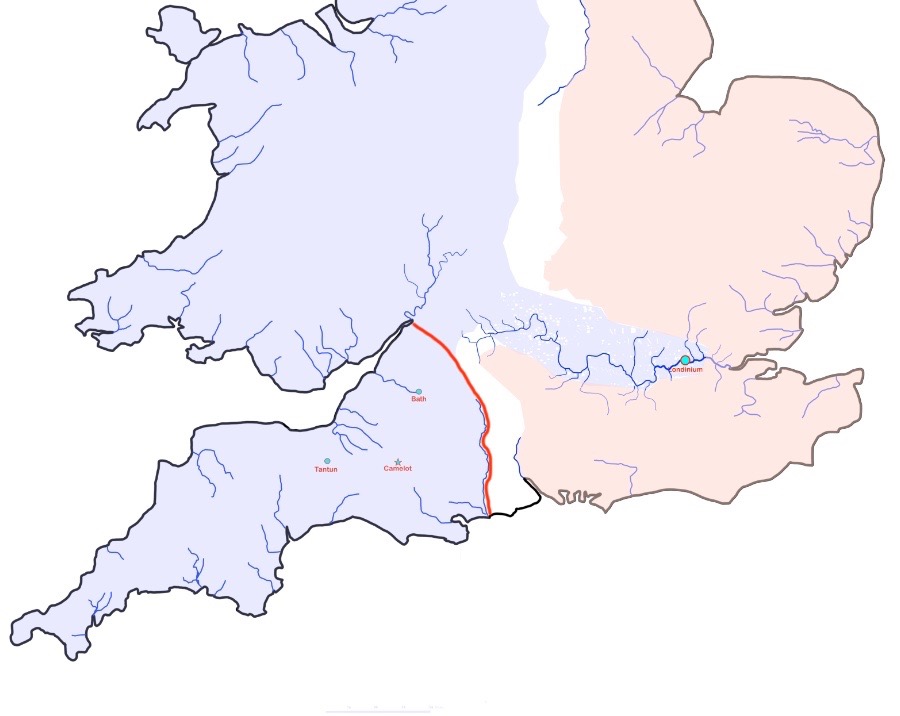

In this map, Briton areas are blue, Saxon-Jute-Angle areas are pink, and the border of Arthur’s lands is in red. I have not yet divided his lands among his sub-kings; I’m opposed to doing so because that imposes dramatically clumsy time delays on the action.

So what was the population of Arthur’s lands? That depends a lot on population densities. The best lands were in eastern England, precisely the areas controlled by the Saxons. I’ll put the total population of the area shown in the map at 1 million, and then divide that fifty-fifty between Saxons and Britons. Of the 500,000 Britons this puts in the blue area, Wales would account for few; I’ll say just 100,000. The Thames value (the blue tongue extending to Londinium) was particularly fertile, so I’ll divide the remaining 400,000 Britons equally between Arthur’s lands and the Thames valley (which I have already assigned to another king whose name I can’t recall.) That results in a total population of 200,000 people in Arthur’s lands.

However, we know that the battles fought during this period typically involved only a few hundred men on each side; The one number we have some certainty on, the Battle of Catraeth, fought around 600 CE, involved 300 Briton mounted warriors (although some scholars maintain they must have been accompanied by a much larger group of infantry.) My thinking is that the Britons relied exclusively on cavalry for offensive operations, which gave them a tactical advantage. We know that the Saxons of the time relied exclusively on infantry. Thus, smaller groups of mounted Britons could defeat larger groups of Saxon infantry. Moreover, I have the impression that the Briton warriors underwent some training, whereas the Saxon infantry was just farmer-militia. Thus, Arthur could manage with an army of just a few hundred men divided among his eight sub-kings and himself.

This brings me to the immediate problem: flour. Specifically, were there any functioning water-wheels in Arthur’s territory? We can be certain that the Romano-British had water-wheels to make flour, because bread was a significant part of their diet. Without water wheels you have to grind the wheat by hand, and that’s too labor-intensive for all but luxury eating. A typical water wheel flour mill could grind about 250 kilograms of flour in a day. If every person gets, say, 250 grams of bread per day (that’s an absolute minimum assuming that they get most of their calories from porridge and gruel), then one such flour mill could feed a thousand people. Arthur’s people would need at least a hundred such mills to provide the population with a minimal amount of bread.

Good. I was thinking that most of the mills would have fallen into disrepair due to lack of maintenance experts, but that’s not possible. I’ll have to re-write my encounter about a water wheel.