Balance of Power uses a term that is unfamiliar to many Americans: Finlandization. Finlandization is an expression of simple anticipation and common sense. The process takes place whenever a polity realizes that its military position is hopeless, and therefore attempts to make some sort of accommodation with superior forces. Although the idealist in each of us may feel disgust at such unprincipled behavior, there can be little doubt that it has saved more lives and prevented more bloodshed than any other form of diplomacy.

History of Finlandization

The term refers to the experience of Finland at the end of World War II. The original story goes back to the end of World War I. Of all the many peoples yearning to break free from the Russian empire at the end of that war, only the Finns and the Poles were successful. The Russians resented the independence of these two nations but were too weak to do anything about it - at least, for a few years. The Western powers, primarily France and Britain, guaranteed the independence of both Poland and Finland. The very first act of World War II was the German invasion of Poland, with the Russians joining in after thirty days to take over the eastern half of Poland. With Poland out of the way and the British and the French fighting the Germans, the Soviets were free to invade Finland. In December, 1939, they attacked. The Finnish forces were outnumbered but fought with great skill, inflicting tremendous losses on the lumbering Soviet columns. Eventually superior Soviet numbers prevailed and the Finns were forced to cede large portions of their land to the Soviets in a dictated peace settlement.

Then came the German invasion of Russia in 1941. The Finns joined in the German attack so that they might recover their lost lands. When the war began to turn against the Germans, the Finns realized their mistake and began to make peace overtures to the Russians. Rebuffed by the Soviets and facing invasion, they turned to the Western Allies. Their pleas fell on deaf ears; they were still allied with Nazi Germany and could not expect to receive protection. Realizing the hopelessness of their situation, the Finns had to accept a humiliating surrender which only preserved their existence as a nation.

Since the end of World War II, Finland has pursued a foreign policy extremely deferential to Soviet interests. While nominally a sovereign state with a neutralist foreign policy, Finland is in practice very much under the sway of the Soviet Union. For example, during Soviet naval maneuvers in the White Sea, a Soviet cruise missile went out of control and flew into Finnish airspace. One would have expected a diplomatic protest and angry denunciations of Soviet callousness. Instead, the Finns quietly collected the pieces of the cruise missile and returned them to the Soviet Union.

[2014: Finland has quietly reversed course and no longer defers to Russia. Instead, it now has non-belligerent diplomatic policy for all nations.]

Although the term Finlandization dates from 1945, the process has been taking place since earliest times. Thus, Julius Caesar reports in The Conquest of Gaul:

These various operations had brought about a state of peace throughout Gaul, and the natives were so much impressed by the accounts of the campaigns which reached them, that the tribes living beyond the Rhine sent envoys to Caesar promising to give hostages and obey his commands...

Acts of Finlandization don’t occupy the prominent place in the history books that the famous battles have; the battles get all the press coverage because they are the turning points that conveniently mark the waxing and waning of a nation’s fortunes. Yet, in many cases the real significance of a battle comes from the acts of Finlandization towards the victor that the battle induces from previously reluctant minor powers. For example, William the Conqueror may have won the Battle of Hastings in 1066, but that victory did not by itself hand over all of England to his forces. There remained considerable military forces on English soil capable of effectively resisting Norman arms. The psychological effect of the battle was to convince all onlookers that William had established decisive superiority, and the remaining Anglo-Saxon nobility made their obeisance to William.

Finlandization can also take place in reverse. A major power that has established suzerainty over a variety of minor powers can suddenly find its position under threat if its prestige or power appears to collapse. The total collapse of the Napoleonic hegemony after his defeat in Russia is a classic example of such an unraveling. By 1811, Napoleon had established hegemony over Austria-Hungary, Prussia, Denmark, Italy, and the Low Countries. Then came the 1812 invasion of Russia and his disastrous defeat. Within six months his subject nations had all rebelled against him. In 1813 came the Battle of Nations at Leipzig, and just about everybody who was anybody was there with an army against Napoleon. Leipzig, not Waterloo, marked the real destruction of Napoleon’s power.

Techniques for encouraging Finlandization

Finlandization is an act of anticipation; it is possible to take the anticipation one step further and anticipate the act of Finlandization. In other words, not only can a minor power anticipate its likely defeat at the hands of a major power, but a major power can also anticipate the intimidating effects of its behavior on minor powers. This creates a whole panoply of behavior calculated to maximize the intimidation of minor powers, such as terror, punitive expeditions, or military demonstrations.

Terror

The most extreme example of such deliberate intimidation was the behavior of Genghis Khan in the first decades of the thirteenth century. The Mongol armies adopted a deliberate policy of terror. When they invested a city, they gave the inhabitants a simple choice: surrender immediately or suffer complete destruction later. Cities that surrendered were forced to give up tribute and hostages, but were allowed to continue their existence. Cities that offered any resistance were obliterated and all inhabitants massacred. The effect of this terror campaign was to create a paralyzing fear of Mongol armies. The stratagem was effective but based on a hideous destruction of human life.

Such brutal techniques have contemporary analogies in the Soviet treatment of rebellious satellites. The Soviet invasions of Hungary, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Poland, and Afghanistan were carried out with a vindictive ferocity exceeding that necessary to restore order. Although the primary goal of these military actions was the reestablishment of Soviet control of the satellite, a secondary effect was to make clear to the other satellites that any rebellious behavior would be met with naked and overwhelming force. The point has not been lost on the Eastern European nations. During the Polish troubles of the early 1980s, all parties - Solidarity, the government, and the general population - lived in dread fear that the Soviets would lose patience with the efforts of the Polish government and put a stop to Solidarity’s efforts in its own way: with a brutal invasion.

[2014: Soviet power collapsed in 1990 but Russian under Mr. Putin continues the policy of terror. Its invasions of Georgia and its ruthless treatment of the Chechens have established a reputation for Russia that frightens its neighbors. Its theft of Crimea and subsequent invasion of Ukraine demonstrated Mr. Putin’s readiness to use military force against its neighbors. Ukraine is succumbing to Finlandization. The Baltic states (Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia) are appropriately terrified of a Russian invasion and are already starting to make submissive noises to Russia.]

Punitive Expeditions

One step down from the deliberate use of terror is the so-called punitive expedition. This is a limited military operation against a weak nation whose purpose is to shoot up the countryside in a fashion calculated to impress the natives with the power of the military forces arrayed against them. The European nations used such techniques against China in the 1880s, keeping it in chaos and subservient to Western trading interests. The phrase “gunboat diplomacy” dates from this period and captures the style perfectly. The American bombing of Libya in 1986 also falls into this category of behavior.

Nonviolent demonstrations of power

At the next lower level of intimidation, we have the nonviolent demonstration of military power. Commodore Perry’s expedition to Japan in the 1850s falls into this category. The Commodore was sent to open up trade with Japan. The warships he brought were merely for protection, but of course, only a fool could fail to see how big and powerful they looked. The Japanese took the hint and acceded to the good Commodore’s suggestions. Within a few years the Japanese began to develop a Western-style navy of their own.

Similarly, the American demonstration of naval power against Nicaragua in 1982 was nonviolent in character yet managed to convey a truly menacing message to the Nicaraguan leadership. The Navy sailed around offshore, looking mean and hungry. While Commodore Perry’s use of intimidation was successful, the American use of intimidation against Nicaragua had no apparent success.

Intimidations of this nature need not be pointed directly at their intended victims. For example, the American invasion of Grenada in 1982 could be regarded as, among other things, an attempted indirect intimidation of Nicaragua.

Diplomatic Intimidation

From here we pass out of the sphere of military intimidation and into more diplomatic channels of intimidation. Here, the trick is to say the magic words that will convince your victim that he is in deep trouble and had better come around to your way of thinking. Adolf Hitler was a master of such techniques; his was the remarkable achievement of successfully conquering Austria and Czechoslovakia using only brutal browbeating, without a shot being fired.

Countermeasures

Some nations may not wish a major power’s attempted intimidation to succeed, and they have a variety of countermeasures available to them. The object of the attempted intimidation might prominently display its military power to demonstrate its resolve to fight. The Sandinista government of Nicaragua has responded to American attempts at intimidation with extensive military displays meant to show Nicaraguan determination to fight. In ancient times, leaders desiring to blunt the intimidating threats of enemy ambassadors would execute those ambassadors. The practice might seem barbaric at first glance; its real purpose was to present the citizens with a fait accompli. Murdering ambassadors guaranteed awful retribution for the entire polity associated with so heinous an act, and so served to win the enthusiastic cooperation of all citizens in the endangered kingdom.

A major power wishing to blunt the intimidations of a rival major power can bolster the resistance of a minor power with assurances of support. This is the basis for treaties of friendship and mutual defense treaties. Indeed, throughout history, the vast majority of treaties between nations took the basic form of a powerful nation undertaking to defend a less powerful nation. By guaranteeing the weaker nation’s security, the stronger nation bound the weaker nation to it more tightly and effectively reduced its sovereignty.

The problem with this technique is that it can be carried out with so much anticipation that it can drag nations into disaster. The genesis of World War I provides the perfect example of how the anticipation and counter- anticipation used in such mutual security treaties can lead to failure. Europe had known peace for forty-five years; during that time it had stabilized a set of delicately balanced power relationships. A web of mutual security pacts was strung across the whole European continent. Germany, wary of Russian pressures on Austria-Hungary, had signed a security treaty with that aging empire. France, fearful of burgeoning German power, signed a security treaty with Russia. Britain was also worried about German naval programs. Thus, when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, it triggered a chain of similar declarations. Russia entered the war in protection of Serbia; Germany declared war on Russia because of its treaty obligations to Austria-Hungary; France thereupon declared war on Germany, and Britain soon entered the fight.

The role of prestige or ‘face’

World leaders are often castigated for going to great lengths to save face. The impression one gets is that these are vain old men who freely sacrifice the lives of young soldiers to preserve their sense of dignity and save face. As it happens, there really is a functional significance to the role of prestige, and the sacrifice of human life in pursuit of prestige is not so monstrous as it first appears.

Prestige confers two benefits in the world of geopolitics: one for friends, one for enemies. High prestige tends to demoralize or intimidate unfriendly nations. They will be less likely to challenge the nation that enjoys high prestige. If a major power’s prestige falls, unfriendly nations will be emboldened to take action against the now-weakened power. This process can mushroom as each act of defiance encourages still others, as Napoleon learned the hard way.

Even more telling is the effect of prestige, or its loss, on a major power’s friends. Every major power collects around it a covey of client states, each of which accepts the risks of association with that power in return for the protection it provides. Their willingness to continue the association with the major power is contingent upon their confidence in that major power, which in turn is closely tied to its prestige. For example, in 413 B.C., Athenian prestige was shattered by twin defeats. An Athenian army and navy at Syracuse, in Sicily, were annihilated, and a Spartan force captured Deceleia, a strategic town not far from Athens. The twin defeats triggered mass defections from the confederacy that Athens had built. Her allies abandoned her, her subject cities refused further tribute, and even the slaves in the mines revolted. Prestige can build empires bloodlessly, but such empires collapse with the loss of that prestige.

The same considerations played a major role in the long agony of American disengagement from Vietnam. As early as 1969, a consensus had been reached that the fundamental American goal was eventual disengagement. Yet, American participation in the war continued on for four more long years, withdrawal being stymied by the problem of minimizing the loss of prestige that a unilateral withdrawal would entail. Henry Kissinger, discussing the problem of North Vietnamese violations of the 1973 treaty, wrote:

We were convinced that the impact on international stability and on Americas readiness to defend free peoples would be catastrophic if we treated a solemn agreement as unconditional surrender and simply walked away from it. And events were to prove us right. (Years of Upheaval)

Roughly 20,000 American lives were expended while this problem was wrestled with.

Finlandization in Balance of Power

Finlandization in Balance of Power presents a simplified version of the considerations described in this chapter. The first task of the Finlandization routines is to determine the extent of military vulnerability of the subject nation. This must be compared with the amount of military threat imposed by each of the superpowers. If a superpower can project a believable military threat against a small nation, and that nation believes that the superpower might actually carry out its threat, then the small nation will Finlandize.

The procedures begin by defining the Military Excess as the military superiority of the government over the local insurgency:

This is the amount of military power that the government has available for defense from outside forces such as a superpower. You will recall from Chapter 2 that the military power values of the government and the insurgency are calculated from the number of soldiers and weapons available to each.

The program then calculates the amount of military power that each superpower can project against the minor country:

In this equation, Intervenable Troops represents the total number of troops that can be placed into the minor country by the superpower. This is itself a complex consideration. A superpower may have a great many troops, but its ability to place them in any country in the world is severely constrained. Unless it is invited in by the government, the superpower will have great difficulty with the logistical problems associated with moving large numbers of troops into a hostile environment. In Balance of Power, this problem is handled in a very simple fashion. If the superpower is contiguous with the minor country, then it can apply the full measure of its power - all of its troops - against the minor country. If it is not contiguous with the minor country, then its ability to send in troops is based on the existence of a third country, contiguous with the minor country in question, in which the superpower has based troops in support of the government. The presumption is that such military installations create logistical facilities which can support the infiltration of military forces across the border. The number of superpower troops that can be used against the victim minor country is then equal to the number of superpower troops based in the neighboring country. For example, the American troops based in Honduras are there primarily to put pressure on the Nicaraguans. Finally, if there is no contiguous country in which the superpower has stationed troops, then the superpower can still send up to 5,000 men. This force represents the small mobile forces that both superpowers keep just for such purposes. It is the basis for our time-honored slogan, “Send in the Marines!”

The Military Power of Superpower is computed in the same way that military power is computed for the minor countries; it is a function of the number of troops and weapons available to the superpower. The Total Troops of Superpower is just that - the total number of men under arms, and is calculated from the total population of the country.

With projectable power calculated, the next step is to determine the amount of military support that the minor power can expect from the other superpower. This is based on three factors: the military power of that other superpower, its treaty obligations to the minor country, and its record of integrity in honoring such treaty obligations. These are expressed as an equation:

To expand on these terms: Treaty Obligation is the extent to which a superpower is committed to defend the minor country. It is dependent on the level of treaty support between the two countries. In Balance of Power there are six levels of treaties, ranging from no treaty to nuclear defense treaty. These treaties create obligations using the following table:

No relations: 0

Diplomatic relations: 16

Trade relations: 32

Military bases: 64

Conventional defense: 96

Nuclear defense: 128

The other strange term in the equation is Integrity, which may surprise the reader. After all, one would not expect to see a variable in a computer program called Integrity, There is certainly something unsettling about the thought of computing integrity. This is one of our finest and most cherished virtues, a hallmark of our moral sensibilities. There is something both presumptuous and outrageous about attempting to reduce so noble a concept as integrity to a few ciphers in a computer program. It borders on sacrilege.

My reply to these reservations is to claim that the attempt to quantify a concept in no way demeans it. If something exists - that is, if it is real - then its very existence implies a set of numbers that characterize its properties. That set may be very large, or very difficult to determine, but they do exist, and making a stab at getting a few of them is not sacrilege. We all know (or should know) that a person’s IQ does not define his or her mental ability; it is only a score on a test and the only thing it tells us with certainty about that person is the ability to answer silly questions about odd geometric shapes. We generalize that number to make statements about the person’s native intelligence, but we realize that we are on very thin ice when we do so. And skating on thin ice is not tantamount to sacrilege. So, on with the computation of integrity.

In Balance of Power, Integrity is a number between 0 and 128. A lying, scheming, no-good varmint gets an integrity rating of 0; a truly honest man gets a rating of 128. Each superpower starts off with an initial integrity rating of 128. This is admittedly a ridiculously generous assessment, but I felt that each player should have the opportunity to make his own evil. A superpower’s integrity is changed whenever a government falls. When this happens, each superpower’s integrity is decreased in proportion to the strength of the treaty commitment the superpower had made to the newly-fallen government. For example, when the insurgents win a revolution, or there is a coup d’etat, the following equation is applied for each superpower:

Thus, if the USA has a nuclear defense treaty (Obligation = 128) with a nation whose government falls, the Integrity of the USA will fall to 0. Ouch! If it had only a military bases treaty (Obligation = 64), then its Integrity would be cut in half.

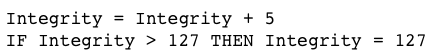

You may notice that this equation will always _reduce_ a superpower’s Integrity. That’s a cynical view of international relations. To correct for this problem, I threw in the following formula and had it executed once each turn:

This formula says, “Look, kid, you keep your nose clean, your reputation will get better each year slowly”. You may ask, “Why did you choose the number 5? Why not 4, or 6, or 20?” Good question! When I wrote that equation, and realized that I had to choose a number, I leaned back in my chair, stared at the ceiling, closed my eyes, squeezed on the eyelids, and watched the dancing phosphenes form the numeral 5.

Does it bother you to realize that some aspects of the game were chosen so arbitrarily? If so, consider the problem of choosing the correct value for the equation. How quickly does a nation’s reputation recover from damage? How could anybody possibly measure this? In other words, there is simply no rational way to arrive at an estimate for this number. There are no books in which to look it up, no scholarly studies, nothing of which I am aware. This leaves only two possibilities: fabricate a number or abandon the concept. I chose to fabricate the number.

Of course, my concoction is not completely without rational basis. We can easily whittle the possible choices down to a number between 1 and 50. For example, any number less than 0 would imply that ones reputation grows worse with time, even if you do nothing wrong. That’s not the way the world works! The number 0 implies that, with no activity on your own part, your reputation does not change. But this formula is meant to reflect the aphorism that “Time heals all wounds”, so we cannot accept a value of 0. On the upper end, any value larger than 50 would imply that one could commit the most heinous crimes and enjoy the absolute confidence and respect of the world only two or three years later. The world’s memory isnt that short. This does suggest the means to narrow down the range of possibilities. How many years should go by before a country’s reputation recovers? A value of 20 would imply complete recovery of reputation in only six years. That seems a little quick to me.

So we know that the final value should be between 1 and 20. But which value to choose? At this point, we have exhausted the possibility of easy solutions. There is simply no reliable way to choose, say, 5 over 6. A good case can be made for any value in this range. And, if it is possible to make a good case for any value, then there is no harm done by choosing one value from this range arbitrarily. If I am unable to determine whether a value of 5 is better than a value of 6, how would a player ever be able to tell that something is wrong with the game if indeed the value I chose was incorrect vis-a-vis the real world? What is the meaning of incorrectness when nobody is able to discern it?

The last bit in the equation that needs explanation is the divisor, 16384. Its purpose is to scale the value back down to the proper range. Since Integrity and Obligation both range between 0 and 128, if both are at full value, they will multiply together to produce 16384. By dividing this figure, we bring the Expected Military Support back to its proper range.

[2014: This kind of calculation is obsolete. Nowadays we just use floating point numbers.]

Now that we have calculated the military support that the minor country can expect from the other superpower, we calculate its total defensive strength:

This number will be used to calculate the Finlandization Probability - the likelihood that the minor country will Finlandize to the superpower in question. The magic equation is:

Now to explain the new terms. Adventurousness is the demonstrated proclivity of the superpower to engage in reckless military actions. It is calculated from the following formula:

Oh no! And you thought I went too far with measuring integrity! Now Im using Pugnacity and (gasp) Nastiness?!?! Where do I get those? Pugnacity is a number between 0 and 128 that is initialized at the beginning of the game to a value of about 64. I say about because a small random number is added to make sure that each game plays slightly differently. Also, the Soviet Union gets a pugnacity rating 32 points higher than the USA, although for me recent events in Libya call into question the wisdom of this assessment.

[2014: The American wars in this century definitely make the USA’s current Pugnacity much greater than Russia’s.]

I will not go into the many details of the calculation of pugnacity and nastiness. Instead, I will say that a superpower’s pugnacity is increased whenever it engages in aggressive behavior, and decreased when it engages in more conciliatory behavior (such as backing down in a crisis). Nastiness is a term that applies to the overall situation rather than to any single superpower. Nastiness is increased by military interventions and crises. It is decreased only by the balm of time. The effect of these two terms is to create a mood to the game. Players who pursue confrontational strategies will increase their own pugnacity and the game’s nastiness. Executed properly, such a ruthless strategy will encourage weak nations to Finlandize to the player. But minor slips can cause the other superpower’s pugnacity to increase and your own pugnacity to fall as you find yourself backing down too many times in crises.

The other new term in the equation is Pressure. This is the amount of diplomatic pressure that the superpower is applying to the minor country, ranging from 0 to 5. This makes it possible for a superpower to induce Finlandization in a minor country that is on the brink. Note that adding 4 to the value of the pressure insures that zero pressure does not mean zero chance of Finlandization.

Consequences of Finlandization

When all these terms are put together, we get a number for the Finlandization probability. If this number exceeds 127, then we say that the country has Finlandized to the superpower in question. This triggers a number of changes. First, the victim changes its political alignment to become more like that of the superpower:

You will recall from Chapter 2 that Government Wing is the position of the government on the ideological spectrum, with far left countries having a Government Wing of -127 and far right countries having a value of +127.

The Finlandizing minor country also changes its diplomatic affinity towards the superpower; it decides to be nicer to the superpower:

Old Diplomatic Affinity is the previous value of Diplomatic Affinity; the degree of good feeling between the two governments. This is an important equation because this is what gives the player prestige points. Prestige points are what win the game for the player, and they are generated by the extent to which the players country is held in esteem by the countries of the world, weighted by their military power.

And that is how Finlandization is computed in Balance of Power.

Europe, NATO, and “neutralization"

For the last forty years, the central strategic problem of American planners has been the protection of Europe. At first this was strictly a military problem, the response to which was NATO, but as time went on the problem assumed more delicate dimensions. The Soviets realized that a simple invasion of Western Europe would be prohibitively dangerous. However, they did not miss the opportunity to play on European fears. The basic strategy was to steadily harp on the enormous damage that would be created by a European war. The intermediate-range nuclear weapons were one expression of this policy. Their purpose was to drive home to the Europeans the fact that Europe could easily become a nuclear battlefield in the event of any conflict. It may surprise some Americans, accustomed to living in the shadow of the Bomb, that the awful significance of nuclear weapons had not quite penetrated the European political consciousness. The Europeans had always thought that a nuclear war would be fought over their heads. They would see the missiles flying overhead, and hear the distant detonations, but would themselves face only the depredations of conventional warfare. All through the late seventies and early eighties the significance of the new Soviet weapons tormented the European public, igniting a storm of protest. The Soviet strategy had the desired effect on a portion of the European public. These people reasoned that the cost of alliance with the United States was too high if it carried the responsibility of being targeted by Soviet intermediate-range missiles. They felt that the superpower competition was not their doing, and they were not willing to risk their homelands in the pursuit of that competition. They therefore argued that a much safer course would be to distance themselves from the United States and take a more neutralist course. Security would come from the same neutrality that Sweden, Austria, and Switzerland had chosen.

This was precisely the course that the Soviet Union desired. If Western Europe could be coaxed into neutrality, NATO would be dismantled and there would exist no effective counter to Soviet power in Europe. A blatant invasion would still be too risky, but strong pressure could slowly be applied to edge the nations of Western Europe into increasingly more accommodating positions. Eventual Finlandization would be the outcome. And the results for the Soviet Union would be spectacular. With Western Europe under Soviet sway, the Soviet sphere would certainly outweigh the American sphere. World hegemony would be conceivable.

This line of thinking, or variations on it, has certainly generated many nightmares for American planners. For example, Henry Kissinger, discussing the European diplomatic overtures to the Soviet Union in the early 1970s, wrote:

A European race to Moscow might sooner or later represent the first steps toward the possible Finlandization of Europe - in the sense that loosened political ties to America could not forever exclude the security field... (Years of Upheaval)

Fortunately, the nightmare lost momentum. The Soviet intermediate range missiles were countered by American cruise missiles. There was much opposition to these cruise missiles at first, but ultimately they were accepted by their host countries. NATO held together.

Variations on Finlandization

There have been many variations on Finlandization throughout history. It seems that statesmen have been very creative in coming up with alternatives to sovereignty or subjugation. Modern Finlandization is a very genteel matter. The victim defers to the superpower in matters of foreign policy, and generally makes nice to the superpower. However, there are many variations on this basic theme. Among them:

The unwilling ally

This has been a fairly common theme throughout history. The little country would really rather be left alone, but the big country needs the assistance of its army to bolster its own military power. Thus, the Soviet Union has imposed the Warsaw Pact on its Eastern European satellites. Napoleon did the same thing when he invaded Russia in 1812; of the 600,000 men in the Grand Army, less than half were French. The bulk of the Army was filled by Germans, Italians, Dutch, Belgians, and Poles who were fulfilling their duties as “brothers of the Revolution”. The effectiveness of such shanghaied allies became apparent during the retreat from Moscow, when the Army melted away. Many of the soldiers died of the cold or were killed by Cossacks, but many others simply abandoned Napoleon.

Ancient Athens used exactly the same procedure to build the Athenian hegemony of the Golden Age of Greece. The Athenian league was, on paper, an alliance of equals with Athens playing the role of first among equals. In practice, Athenian behavior was closer to that of superpower dictating to allies who dared not contradict their master.

The vassal

This was a feudal concept originating in German tribal structures. Society was organized on simple hierarchical lines. Every man had his superior, or liegelord, as well as his inferiors, or vassals. The vassal owed service to the liege; in return, the liege was obligated to provide protection to the vassal. The concept was applied from the very bottom of society right up to the very top, and so was applied to international relations. A weak leader might seek the protection of a strong one by offering himself as vassal. More commonly, a strong leader might use whatever pretext he could concoct to assert liege rights over a weak leader. It is misleading to compare this directly with the modern concept of Finlandization, for all society was organized along such liege/vassal lines, so the creation of a new liege-vassal relationship could be called an act of annexation or an act of Finlandization.

Tribute

This technique was used throughout ancient history. A weak nation would send regular payments to a powerful one. The system was remarkably similar to the concept of protection money that we see used by street gangs. The victim makes regular payments to the stronger party. In return, the victim obtains two benefits: the victim is not molested by the strong party, and the strong party acknowledges a vague responsibility to protect the victim from other molesters. This responsibility is not strong enough to allow a victim to demand action when it is molested; it is rather a matter of the strong party protecting its territory from incursions by other molesters.

Buying off

This was a variation on tribute, normally used by powerful nations with pesky nomads. The powerful nation is not actually weaker than the nomads, but does not have the resources to eliminate them. Instead of maintaining extensive military forces to protect the frontiers from their raids, the powerful nation simply sends them a payment every year. The payment does not constitute tribute and no subordinate status is implied. It is just a simple buying off of a nuisance. For example, the Eastern Roman Empire used this technique to keep the Huns off its back. Even at the height of their power under Attila, the Huns did not constitute a serious threat to Constantinople, but they had beaten several Roman armies and could wreak great damage in the Balkan provinces, so Emperor Leo agreed to pay an annual tribute of 2,100 pounds of gold.