The invention of the alphabet was one of the crucial steps in the development of sequential reasoning, but it was a complete fluke. The alphabet was not invented by some brilliant Egyptian or Mesopotamian writer seeking a better way to put ideas down on paper. It was instead an extension of an idea that had developed in both Mesopotamia and Egypt: syllabic writing.

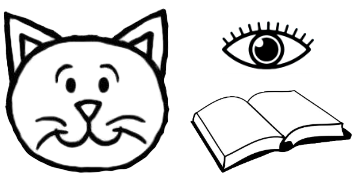

This started off as a kind of shorthand system. The first step was to build new words out of the first syllables of existing logograms. The actual implementation of this in Egyptian writing was a complicated mess involving the addition of various other symbols to disambiguate the multiple possible interpretations. But the key idea was the partial use of the visual symbol — the logogram — to represent the pronunciation of a different word. Here’s a hypothetical example. This image presents the logograms for two words: “cat” and “read”. However, in this syllabic system, we would use only the beginning sounds of each of the two words: “ca” and “re”, which we pronounce as “carry”. This word means “carry”.

Both the Egyptians and the Mesopotamians used syllabic systems like this to augment their written languages. This was an immensely important development, because it replaced the visual interpretation of the writing — what it looked like — with the phonetic interpretation of the writing: what the words sounded like.

From there it was a short step to taking the process one step further and using a sign to represent a single sound. We call a sign that represents a single sound a “letter”, and there are two types of letters: consonants and vowels. Together, consonants and vowels comprise an alphabet.

This was a vastly simpler system, for two reasons: first, you don’t have to memorize 5,000 pictographs to read and write; you must memorize only the few dozen letters in the alphabet. Second, it’s far easier to translate the written word to the spoken word; you just pronounce the sounds of the letters in sequence. Of course, that only works if the words are spelled phonetically, which is sometimes not the case, especially in English.

Unfortunately, the early Semitic writing system was closer to what we think of as stenography than writing. It lacked three elements that we consider critical: vowels, breaks between words, and punctuation. Semitic writing was a continuous stream of consonants representing the flow of spoken language. Now, these deficiencies might seem fatal, but in fact the writing system worked, after a fashion. For example, vowels are not the most important components of words, a fact that we make use of whnvr we cntrct wrds to gt shrtr sntncs. Breaks between words are nice,

butifyouthinkaboutitmostofthetimeyoucanfigureoutthewordswithoutanybreaksbetweenthem. And punctuation is quite helpful, but it was developed slowly over the course of more than a thousand years. Before then, punctuation was considered a crutch for slow readers.

Whatever the weaknesses of the Semitic writing system, we think that it was first invented somewhere in the neighborhood of the Sinai -- that, at least, is where we find the earliest documents written in the new alphabetic system. The Phoenicians, a Semitic people, were the first society to use alphabetic writing on a regular basis. This was likely due to the fact that they were heavily involved in trade. They started off supplying cedar to the Egyptians, and then expanded their operations into other product lines. Literacy is important to merchants because sales orders are best written down rather then memorized (for example, “Do they want eight or eighty tons of lumber?” “Uh, gee, I thought they said eighty, but now I’m not sure.”) The Phoenicians were far-flung travelers; they spread their alphabet all around the Mediterranean; the Greeks, Minoans, and Etruscans appear to have gotten their alphabets from the Phoenicians.