October 28th, 2012

People had figured out the value of sails very early in human history, but only as an opportunistic way to utilize an advantageous wind. If the wind wasn’t going in the direction they wanted to go, they didn’t bother raising the sail. This severely limited the use of wind power; more important, it meant that every single seagoing vessel required a crew of rowers large enough to move the ship at a respectable speed. Seagoing ships were flat-bottomed so that they could be dragged up onto the beach at night. (That was another restriction: without lots of experience about where the rocks were, nobody dared sail at night.)

However, there was still progress in shipbuilding and navigation. Shipbuilders learned how to make larger boats by mastering the techniques of building strong keels. The keel is the backbone of the ship; it runs along the bottom of the ship from front to back. It has be strong because everything else is built on top of the keel. Moreover, it must be able to handle “hogging” – the tendency of a ship encountering high waves to break its back as it traverses the waves. During much of the second millennium BCE, this was accomplished with a “hogging truss”, a pair of heavy ropes tying the stem to the stern. Obviously, hacks like this prevented ships from growing larger.

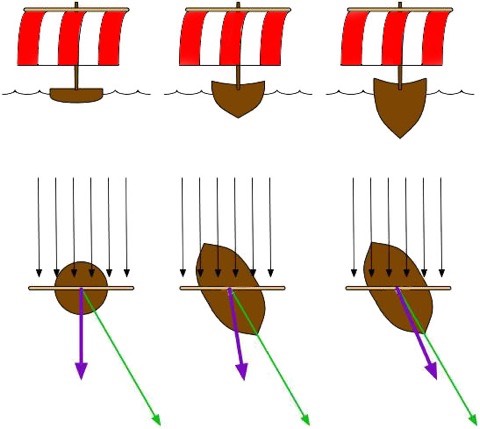

However, by 1800 BCE, the shipbuilders of Crete had integrated a number of improvements to create a new class of larger, more capable ships. These ships had strong composite keels, a crescent shape that better handled ocean waves, and improved rigging to permit more flexible use of the sails. They were still primarily oar-driven, of course, but they could give the rowers a rest more frequently. Even so, they were still faced with a serious problem. Consider three possible designs for a ship:

The boat on the left is a simple raft with a sail; it will go wherever the wind blows. If the sailor wishes to go in the direction of the green arrow, he’s out of luck; there’s little he can do other than to row frantically in the desired direction. And in fact, the Minoan ships carried several dozen sailors to row the boat in the desired direction. A typical Minoan ship might be 20 meters long, with a cargo capacity of 10 tons. Unfortunately, the 30 sailors that this ship carried, along with their water, bedding, belongings, water, and food, probably weighed about 2 tons, reducing the cargo capacity by 20%.

Consider now the middle ship in the diagram. It has a shallow keel and so it can steer a few degrees off the direction of the wind without toppling over. The wind may push it downward, but the water’s resistance to the keel will push the boat somewhat towards the right. The deep-keeled ship on the right presents even more of an obstacle to the water and can therefore steer even further from the direction of the wind.

This was the problem for all the Minoan ships. They had shallow keels (so as permit them to drag the boat up on the beach at night) and so were at the mercy of the winds and had to stick close to shore. The journey from Egypt to Crete ran along the eastern coast of the Mediterranean, the southern coast of Turkey, and thence to Crete. It took three months. With those kinds of travel times, and the costs of all those oarsmen, only the most profitable merchandise was worth trading. The Minoans confined their trade to precious luxuries such as amber, dye, gems, and metals.

In those days, there was no distinction between a warship and a merchant ship; a ship was a ship and could be used for either function. The Minoan navy spent some of its resources stamping out piracy, but the rest of the navy, having nothing better to do, engaged in trade. That trade in turn enriched Minos. Few several centuries, Minoan civilization enjoyed a burst of energy and creativity that vaulted it into prominence in world history.

Around 1600 BCE, the volcano on the island now called Santorini erupted with such violence that most of the island simply disappeared. It is estimated that tidal waves a hundred feet high devastated the north coast of Crete, a hundred miles away. Minoan culture went into decline, and was destroyed a few centuries later by Mycenaeans from Greece.

The Minoan economy was the world’s first to enjoy significant benefits from trade. As with England three thousand years later, Minos enjoyed a privileged position due to its dominance of the seas, and it was able to rake in big profits from its trade, profits that pushed its economy into the stratosphere. Minoan seafarers were probably the first in the world to engage in regular blue-water navigation, sailing directly from Crete to Egypt using the favorable northwesterly winds that predominate in that area. To get home, they had to take the slower route by rowing their way up the coast of Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria, then westward along the southern coast of what is now Turkey.

Although trade boosted the Minoan economy, it remained only icing on the economic cake; it didn’t constitute cake itself. The Minoans got richer because of their trade, but their economy was not dependent upon trade. And they were a palace economy, so the greatest benefits of trade (coming from matching supply to demand) were beyond the reach of the Minoans.

Next story: the Bronze Age Collapse