The theological question that gave Christianity a kick in the general direction of science seems absurd today: can God make a vacuum? On the one hand, Aristotle had explicitly declared that a vacuum was a physical impossibility, and had presented a fairly solid argument to support his assertion. But the theologians insisted that God could do anything he damn well pleased, including making a vacuum. This led to all manner of complex disputations. Yes, God could perform miracles, but could he make 2 + 2 = 5? Could he violate basic laws of logic? Could he make all men mortal, and make Socrates a man, yet make Socrates immortal? The arguments raged.

After that argument grew stale, a few Christian scholars wandered off to explore other areas of Aristotelian thought. A few stumbled onto something that later turned out to be a major milestone in the development of Western thought: the trajectory of thrown rocks. I find it ironic that the consideration of thrown rocks would mark a turning point in the history of science.

Aristotle had explained the motion of a thrown rock in the following fashion: when we throw a rock, our hand imparts something to that rock. I won’t call it “momentum” or “energy” or “impetus” because those are modern terms with a defined scientific meaning. Instead, I’ll call it “going-ness”. The hand gives going-ness to the rock, which makes it go. So it goes up into the air. Once it is in the air, there’s no longer a hand giving it going-ness, but the air in front of the rock is pushed around behind it, where it pushes the rock forward. This process eventually loses strength, at which point the rock falls.

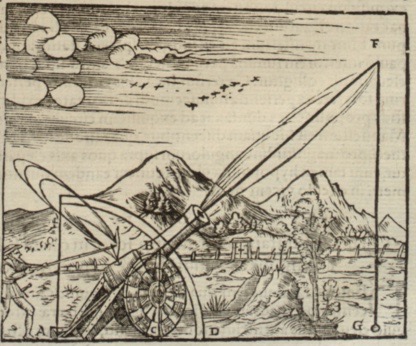

A particular oddity of Aristotle’s explanation is his claim that the rock moved in straight lines. Hence a cannonball would follow this trajectory:

It goes up, then falls straight down. How in the world, you ask, could Aristotle believe such obvious nonsense? Here we encounter one of the greatest flaws in Greek thinking: excessive reliance on abstraction. Greek thinkers revered abstraction so much that they insisted that the universe must operate in an abstractly pure fashion, but the many forms of “dirty reality” obscured the pure reality. If a thrown rock did not move in straight lines, that was only due to petty engineering details arising from wind or birds or the odd shape of the rock. In its heart, the rock “wanted” to move along a straight line, and it would if it were not for all the messy interferences.

The Christian scholars were not so reverent about this notion of pure abstraction; rocks just don’t move the way Aristotle claimed they did. They wrung their hands and struggled with the problem. Their progress was murky, but by about 1350 CE, four of them, collectively known as the Oxford Calculators, had made a huge discovery: they resorted to using numbers.

The modern reader will find this discovery almost laughable. Any child can use numbers! What the modern reader does not appreciate is that, back then, numbers were really hard to use.

Huh?