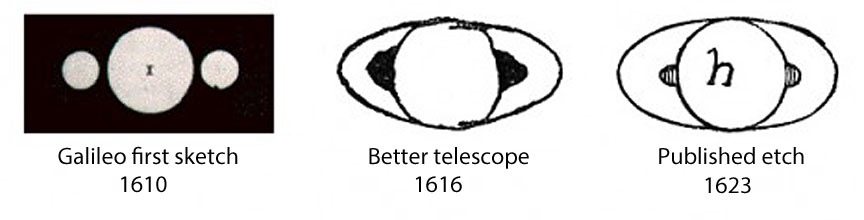

Galileo started it. Unlike most of his predecessors, he was not a priest; he was instead a professor of mathematics. He had a number of nice accomplishments under his belt when, in October of 1508, a Dutch lensmaker by the name of Hans Lippershey applied for a patent for a device that placed two lenses in a line so that, by looking along the line, one could see a magnified image of a distant object. In other words, a telescope. Word of the idea spread like wildfire among Europeans (in itself a powerful demonstration of the intellectual value system of Europeans), and Galileo heard the story early in 1509. He quickly figured out how it must work, then ground his own lenses and built his own telescope. Back in those days, glass was nowhere near as clear or as homogeneous as it is today; Galileo built more than a hundred telescopes and considered only ten to be worth using. His first good telescope was a meter long and magnified the image only nine times. This is about as much magnification as you get with regular binoculars. However, his telescope had a much smaller field of view than you get with binoculars. To give you an idea of just how bad Galileo’s telescope was, here are three drawings Galileo made of Saturn over the years as he improved his telescopes:

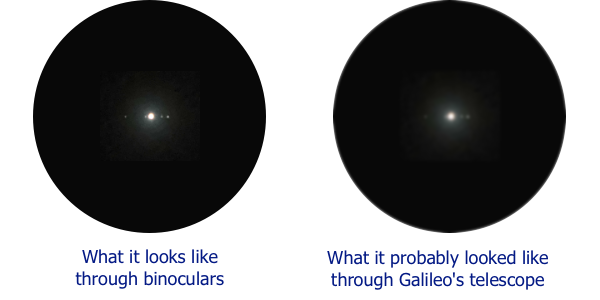

Here’s my rough guess as to what Jupiter might have looked like to Galileo:

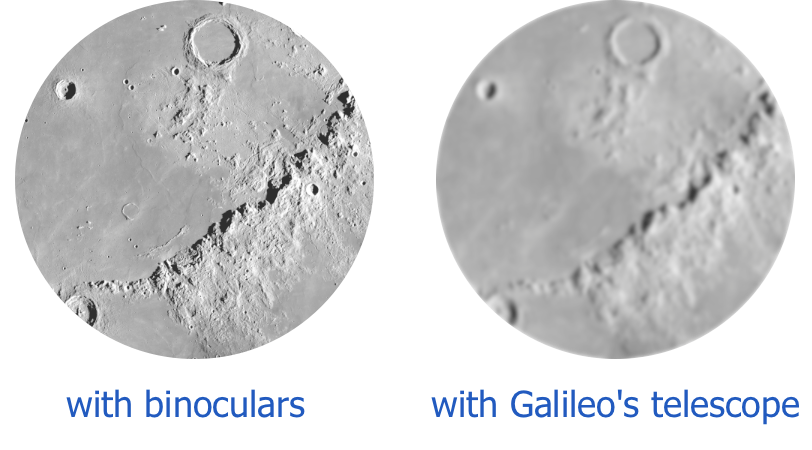

The image was tiny and fuzzy. Yet by patient watching, Galileo managed to build up a clear mental image, and he figured out that there are four moons and that they are orbiting around Jupiter. He also looked at the moon and again saw that its face was covered with mountains and craters. Again, here is a side by side example of what a section of the moon would likely have looked like to Galileo:

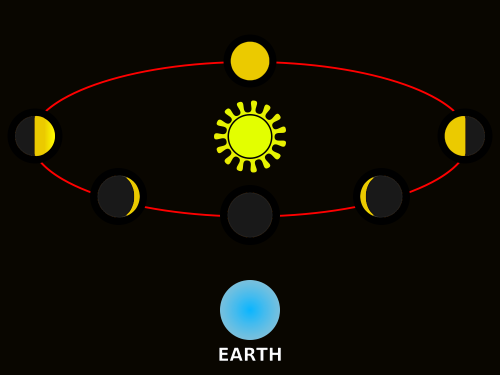

This was shocking enough, but what really corked it was Galileo’s observations of Venus. He had built a more powerful telescope; this is my guess as to what he saw. You have to look closely to see the effect. In the first view on the left, Venus is a tiny round dot. In the middle view, it’s larger and it looks like a half-moon. In the rightmost image, Venus is much bigger and it looks like a crescent moon.

If you have good spatial imagination, you can see how this happened:

This, of course, assumes a heliocentric solar system. There is no way to explain the phases of Venus with the geocentric model. Here Galileo had compelling evidence in favor of the heliocentric model. He rushed to publish his findings in 1610, after just a year’s observations. His book was The Starry Messenger and it caused a sensation. Sadly, most people who tried to replicate Galileo’s observations were using inferior telescopes, and many were unable to see the effects Galileo described. But as other telescope makers improved their work, more and more people were able to see with their own eyes that Galileo was right.

This caused quite a stir. Galileo did not come out in The Starry Messenger and say flat out this proved the heliocentric model. He didn’t need to; it was patent from the drawings. But he prudently made no published comment on the issue. Nevertheless, most of Europe could see the obvious, and rumors abounded that Galileo had come out in favor of the heliocentric model, in violation of Church teachings.

This created quite a quandary for Pope Paul V. He was no Bible-thumping fool; he was well educated, probably knew about Copernicus’ work, and respected Galileo’s work. Sadly, there were still plenty of Bible-thumping fools in the Church hierarchy, and Paul V knew that he couldn’t simply ignore their baying. Some of them wanted to burn Galileo for heresy for merely implying that the geocentric model was wrong. Paul V wouldn’t permit that, but he had to come up with some way to keep the fools quiet. So in 1615 he invited Galileo to Rome where he feted Galileo in banquets and celebrations, and had long discussions with Galileo. Paul V was smart enough to understand Galileo’s work clearly. He described his political problem and suggested a solution: Galileo would be free to continue his researches, with the full public approval of the Church. He would be protected from any attacks by any cardinals or bishops, but he would maintain the fiction that the heliocentric model was a mathematical model only, that it did not represent the real world. Galileo was free to point out that the heliocentric model explained the data better than the geocentric model. The only thing he couldn’t say was that it was the actual truth. Paul V reminded Galileo that all the intellectuals understood full well that the heliocentric model was correct; Paul wanted only that Galileo maintain the appearance the he wasn’t contradicting Church teachings.

This was actually a generous and statesmanlike solution to an otherwise impossible problem. It kept the dogs at bay while preserving Galileo’s work. Galileo agreed. They wrote up a long letter presenting the terms of the deal — although it was phrased as a letter of instruction from the Pope to Galileo. Both signed the letter. Paul V had a few more gala celebrations for Galileo, gave him some expensive gifts, and sent him back to Pisa in triumph.

And so things sat for nearly 20 years. Then in 1632 Galileo did something incomprehensible: he published Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. He published it in Italian, not Latin, thereby reaching the largest possible audience. In it, he ridiculed the geocentric model and those who espoused it. Worse, he put some of Paul V’s own words into the mouth of a character named Simplicius, which translates to “Simpleton”. He broke his promise to Paul V in the cruelest possible manner; the book was definitely a poke in the Pope’s eye.

It is difficult to understand what Galileo was thinking. Did he think that he had become so famous that even the Pople couldn’t touch him? Was he trying to commit “suicide by Pope”? There is no plausible explanation of his action.

Of course, the conservatives in the Church resumed baying for Galileo’s head, and the Pope was rightly furious with Galileo’s impertinence. He commanded Galileo to come to Rome to face trial.

The trial of Galileo is widely misunderstood. In the first place, it was not about which model of the solar system was correct. The trial addressed just one question: did Galileo violate the letter of instructions that he had signed in 1515? It was an open and shut case — Galileo was unquestionably guilty as charged. And the charge was extremely serious: Galileo had not only broken his word to the Pope, he had also violated explicit written instructions from the Pope himself. People had been burned at the stake for far less.

The conservatives thought that they had Galileo dead to rights, but first Pope Leo V forbade them to house him in the dungeons, as was standard practice in those days. Instead, Galileo was put up in a palace with his own servants and fine food. The Pope also forbade the use of torture on Galileo — another astonishing violation of standard practice.

Galileo admitted everything. Yes, he had signed the letter presenting his agreement with the Pope. Yes, his book had violated that letter. Nevertheless, the trial dragged on for months because the Pope wanted every i dotted and every t crossed. They accumulated piles of testimony on every possible aspect of the case.

The verdict was never in doubt: Galileo was guilty. He must have expected to die, but again the Pope foiled the bloodthirsty conservatives. He limited the sentence to life under house arrest. Galileo spent the rest of his life confined to his villa, with his daughter running errands for him and guards posted outside. Galileo was forbidden to publish anything. Yet somehow he managed to get letters and book manuscripts smuggled out of the house and on to Germany where they were published. Wink, wink, nod, nod.

So the mythology about Galileo the hero of science standing up to the hidebound science deniers of the Church is total BS. The most important lesson from this story is an old adage I often repeat: the truth is always more complicated than you think.

April 26th, 2018