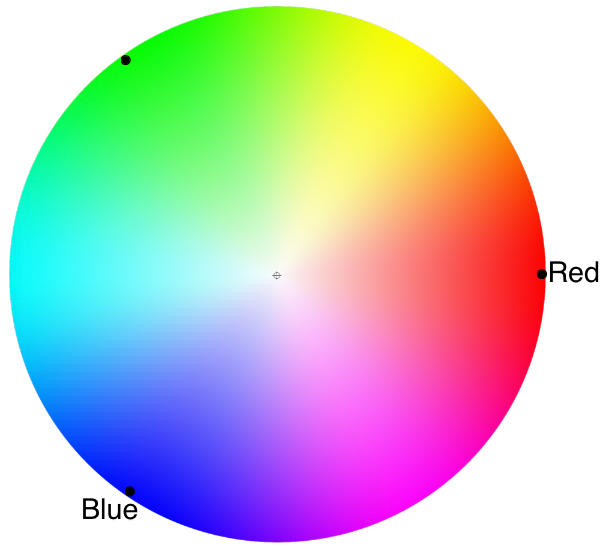

What do the words ‘red’, ‘green’, and ‘blue’ mean? Here’s a color wheel:

I have placed little dots at the positions corresponding to the official definitions of the three colors. So, does the word ‘red’ mean the color that would be underneath its dot? Well, no… most of us would agree that the word ‘red’ covers a wider area of the color wheel, something like this:

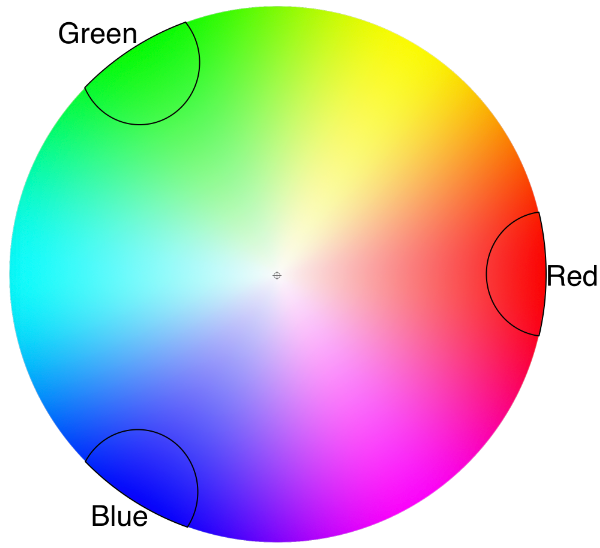

The word ‘red’ would mean any color inside the semicircular area. Of course, you might draw those regions a bit differently, including more or less area as being ‘red’. The same thing applies to the green and blue regions.

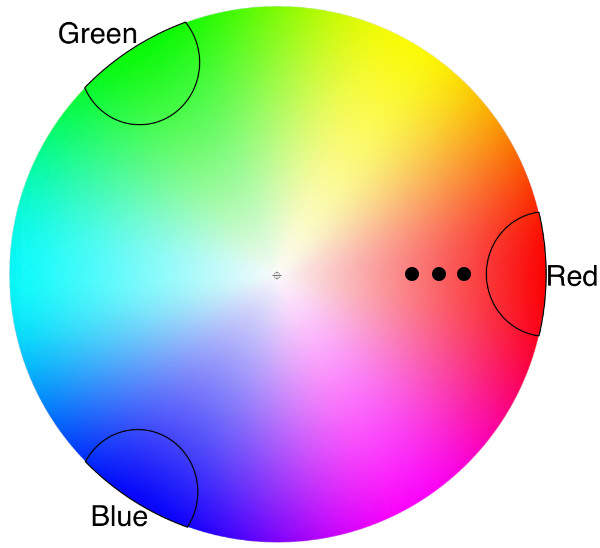

We could take this one step further, with splotches indicating that the word ‘red’ could be applied even further away from our center, but with lessened correctness. For example, in this color wheel, there are three dots:

We could say that all three dots are red, but the word ‘red’ doesn’t fit them perfectly, and the further away from home territory the dot is, the less appropriate the word ‘red’ is.

Semantic space

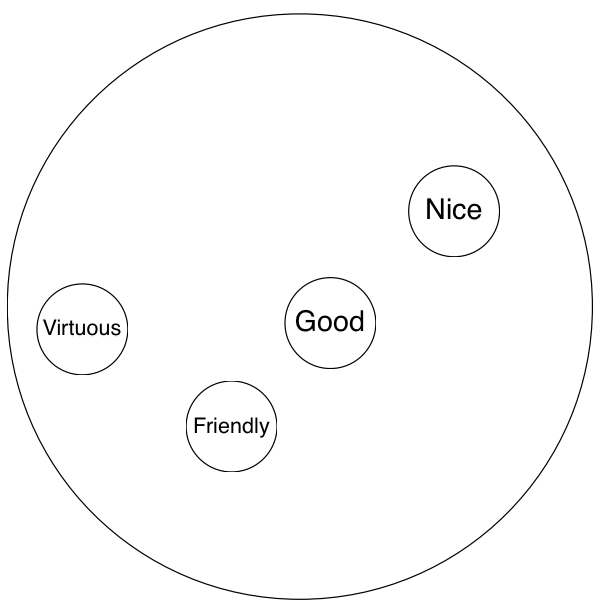

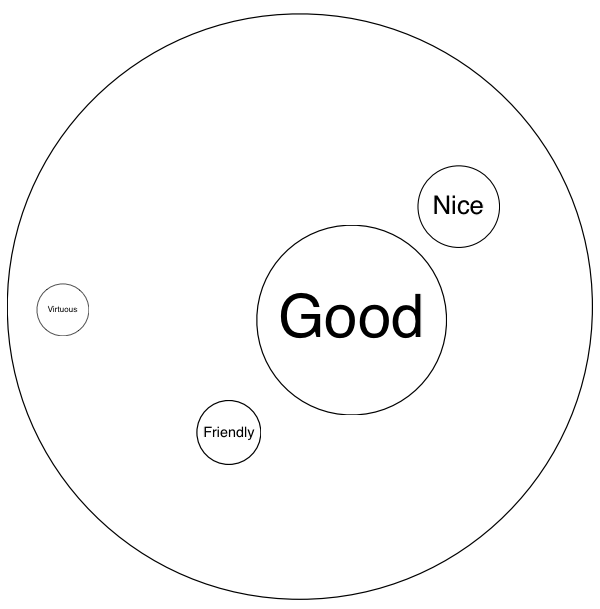

Now we’re going to take these concepts and apply them in a different universe: semantic space. This space covers meaning, not color. Here’s an example of a region of semantic space:

Here are four words with similar meanings. They occupy an imaginary region called ‘semantic space’. The word ‘friendly’ is close to the meaning of the word ‘good’. The word ‘virtuous’, on the other hand, doesn’t mean quite the same thing as ‘good’, so it’s a little further away. But we need to make a further improvement on this diagram:

The idea here is that the word ‘good’ covers a lot of semantic territory: it can mean a lot of closely related things. On the other hand, ‘virtuous’ has a narrower meaning, so it doesn’t cover as much semantic space. We might even draw some of these words with overlapping meanings, so that their circles intersect.

The amount of semantic space taken up by different words varies hugely. The word ‘get’ covers an immense amount of semantic space; the word ‘syzygy’ covers a tiny dot of semantic space. Often a word starts off covering a small amount of space, but then spreads out, like the beer belly on a middle-aged man. ‘Arrogant’ is such a word; initially it meant something like ‘taking for oneself privileges to which you have no right’. Now people use it to mean ‘proud’. Harrumph!

Empty Semantic Space

Next we come to an interesting problem: empty semantic space. These are ideas for which no specific words exist; to express such ideas we must use a compound of several words. For example, we could describe a color as ‘reddish orange’ or ’sky blue’. Some concepts are so complicated that we must use long compounds of words, like ’the gunk that collects under your mouse and blocks the laser’. If a concept like that attains a certain amount of frequency of use, people will shorten it to something like ‘mouse gunk’; if it continues in heavy use, they’ll contract it to something like ‘mogunk’.

Even so, there remain lots of concepts that just have no expression in any given language. This is made clear by examining the vocabularies of other languages. A great example of this is the German word schadenfreude, meaning “pleasure one experiences when learning of the misfortune of someone you dislike”. You know the experience, but you don’t have a word for it. A fun compilation of such words is The Meaning of Tingo, which has such jewels as areojkarekput, an Inuit word meaning ‘to exchange wives for a few days only’ and nakhur, a Persian word for a camel that won’t give milk until its nostrils are tickled. I particularly like the Japanese word yugen, describing a sense of unity with the universe that’s so deep and profound that you are otherwise at a loss for words.

We usually handle such situations by stretching the meanings of existing words to cover otherwise empty space. Thus, most words have a central focus of meaning surrounded by an aura of possible application:

Historical and Cultural Variations

Now I can come to the real point of this essay: we use modern words to describe ancient situations to which they don’t apply. A good example of this is our use of the word science in ancient contexts. The word is derived from the Latin word scientia, which meant ‘knowledge’. We think of science as a system of ideas developed under rigorous standards we call ‘the scientific method’. To us, the word incorporates such notions as hypotheses, theories, experiments, and data.

None of that existed before about 500 years ago. The Greeks did indeed study the physical world, but the methods they used come nowhere near what we think of as science. They observed the world, thought about it a great deal, and made a lot of good guesses. If you wish to define ‘science’ as ‘any knowledge of the physical world’, then I suppose that you could apply that word to the efforts of the Greeks. But by doing so, you minimize the vast difference between their thinking and our own.

By my stricter standards of definition, China never developed science. Sure, the Chinese learned a great deal about the natural world, but it was hit-or-miss guessing based on random observations. It was not based on a logical analysis of how to learn in a way that guaranteed the correctness of their conclusions.

The key idea here is that applying our word ‘science’ to the work of the ancients is misleading. Yes, they learned a great deal about the natural world, but it was not at all comparable to what we call ‘science’. Our notion of science was developed over the course of centuries between about 1200 CE and 1600 CE. Few people have any idea of how difficult that process was, how European thinkers groped about trying to get a solid handle on the problem of learning about the physical world in a rational manner. The history of ‘science’ during those times is really messy, because scholars were struggling with fundamental notions that we all take for granted. The first true scientist, in my opinion, was Galileo, starting in 1610.

Political and social terminology

It is in political and social issues that the extrapolation of terminology back into history is wildly misleading. This is fairly easy to understand in the extreme cases. Let’s imagine a troop of a few dozen hunter-gatherers roving through the savannahs of eastern Africa a hundred thousand years ago. They shared food—does this make them ‘socialists’? How much ‘freedom’ did they have? How ‘oppressive’ was their governing system? Were they Republicans or Democrats? These concepts just don’t apply to these people; they are modern concepts that apply to modern civilization, and so the words should not be used in that context.

Let’s jump forwards in time to the Classical era (Greeks and Romans). Some of our modern words for political and social concepts can be applied. For example, some of the Greek city-states were kinda-sorta democracies. Sure, lots of decisions were made by popular vote, but only a tiny fraction of the population was allowed to vote. There was no concept of ‘rights’ or even ‘freedom’. They condemned Socrates to death on flimsy grounds. If you crossed a powerful person, he could ruin your life and you had no legal protections.

Believe it or not, the first inklings of the idea of ‘rights’ came from the barbarian Germanic peoples who brought down the Roman Empire. They were a messy hodge-podge at first, but over the centuries, the concepts developed. There’s no point in history prior to the Constitution of the United States to which we can point and say “Here is where rights began”. The Magna Carta kinda-sorta specified something like ‘rights’, but they were applied only to a few people and under narrow circumstances. Our current notion of universal, perpetual rights that cannot be abrogated except under narrowly defined circumstances is only a few centuries old. Thus, it’s silly to use words like ‘freedom’, ‘liberty’, or ‘rights’ when talking about the Classical period. Modern translations of Latin histories might use those words, but what the Romans meant by their words does not properly correspond to what we mean by them.

Racism?

I recently read an essay by a fellow claiming that Mount Rushmore is a stain on this country because the men it memorializes (Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Roosevelt) were all racists. Let’s put aside the preposterous notion that Mr. Lincoln was a racist and address Mr. Washington and Mr. Jefferson. They both owned slaves; isn’t that proof that they were racists?

First, the very word ‘racist’ is a modern notion; it didn’t exist in their time. Here’s the Google NGram diagram for the word ‘racist’. It shows the frequency with which the word appeared in Google’s vast corpus of digitized books over the course of time.

As you can see, the word ‘racist’ didn’t start to gain any currency until about 1940. It’s wrong to apply a word expressing a twentieth-century concept to people in the eighteenth century. You might as well call Washington a ‘Republican’ and Jefferson a ‘Democrat’. Was Washington a litterbug if he dropped a dirty McDonald’s wrapper on the road as he rode along? Was Jefferson a polluter if he dumped the ashes from his fireplace into a stream?

Attitudes towards death

Here’s another example of how ignorance of history leads to false judgements. Let’s consider the Roman games in the Colisseum, in which people killed each other for the entertainment of the crowds. Even worse, they’d feed criminals and Christians to wild animals and the crowd got a big kick out of watching the sufferings of these people. “How barbaric!” we think. We cannot imagine how anybody could be so unfeeling as to actually enjoy the death throes of other people.

This attitude bespeaks ignorance of the conditions under which people lived in those days. We regard death as a distant prospect, something that happens only to the very old or the very unlucky. That’s the way things are today; that’s not at all how things were for most of human history. Back then, death was commonplace. Half of all children died before the age of five. Most adults died before their fortieth birthday; anybody older than forty was considered old. Sure, there were people who lived into their seventies or even eighties, but they were the remarkable exceptions that people talked about.

Death struck arbitrarily. People had no idea of disease or its causes; they just knew that somebody could fall ill and die for no apparent reason. Accidents were commonplace; you could be crushed by a runaway wagon, mauled by a mad dog, or beaned by something falling off a building. What we would consider a minor injury often led to death from infection. Crime was widespread; you could be murdered at almost any time for almost any reason. Back then, death was as common as the common cold.

This is why people throughout most of history took such a light view of death. Death was the one absolute certainty of their lives, so they were not as terrified by it as we were. Everybody knew lots of friends and relatives who had died. Sure, nobody wanted to die, but there was no use in getting all worked up over the inevitable. Just going about your daily business in a big city, you were likely to pass at least one dead beggar whose body had not yet been carried away. Wagons carrying bodies were a universal sight.

Thus, when Roman crowds howled in delight watching two men cut each other up, they were merely watching a more dramatic version of something they saw every day. A dull everyday experience was dressed up, amplified, and made exciting.

Before you get carried away with your sense of moral superiority, I challenge you to watch this video without laughing.

Times change; cultures change. Condemning our ancestors for what you suppose to be moral failures reveals not only that you are snotty, but also that you are ignorant.

And don’t forget that people a hundred years from now will be condemning us for our gross moral failings.

January 22nd, 2020