https://www.economist.com/The Internet makes it so easy to acquire almost any information you want. If you develop a knack for composing good search phrases, you really can find out almost anything. For example, I just entered the search words Bulgarian potato production and got 5,860,000 hits with all sorts of fascinating facts about growing potatos in Bulgaria. Did you know that in 2013, Bulgarian farms achieved a potato yield of 121,439 hectograms per hectare? That was a bad year; the next year, they got 129,986 hectograms per hectare. Golly gee!

The problem is that information on the Internet tends to come in small chunks. The typical web page has maybe a thousand words. Reading lots of text on the web just doesn’t work well; people turn away from long web pages. As a consequence, we don’t see much intellectual depth on the web. If you really want to understand the world, books are still the only way to learn.

Here’s an illustration of just how limited the Internet can be. I searched the web for “Desiderius Erasmus”. I got 2,690,000 hits — about half as many hits as I got for Bulgarian potato production. The top hit was the Wikipedia page, which has a few thousand words about him. It also has links to some other sources, most of them pages with a few thousand words. Project Gutenberg has 18 of his books, some of which are duplicates. A few other places provide the text of some of his books.

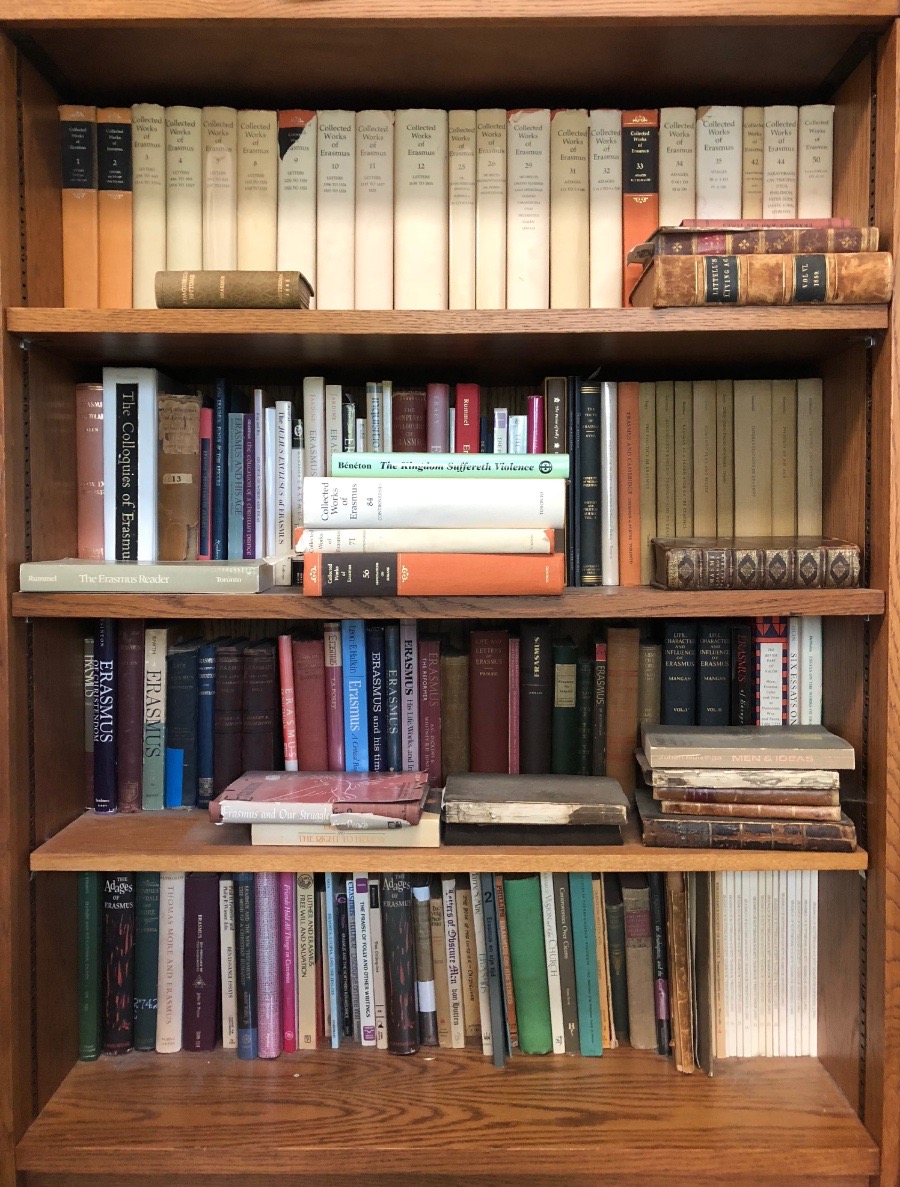

Here’s a photograph of part of my Erasmus library:

Does this give you an idea of just much bigger the world of books is than the Internet? If you want to be able to think well, you must stock your mind with an adequate diet of information about how the world works. I can offer some recommendations.

First, for news, I recommend the newsmagazine The Economist. Yes, it’s expensive; something like $150 per year. But it’s worth it. American newsmagazines are sensationalist, concentrating on pretty photographs and stories about airplane crashes. The Economist is more like history as it’s happening. I am grateful to Eric Goldberg for introducing me to The Economist by a gift subscription. I have subscribed for more than thirty years now and learned a great deal from it.

Now for books. Here, in order of worthiness, are some books that I recommend:

The Story of Civilization, by Will and Ariel Durant. It’s eleven volumes long. It was written more than fifty years ago. It is the best history of Western civilization you can read. I have never seen a decent one-volume history of Western civilization; there’s simply too much material to cover in a single volume. The condensations I have seen don’t make much sense because they’re simply an avalanche of events that can’t be tied together into a coherent whole. The entire set typically costs about $100, but you can buy a single volume for maybe $15. If you do want try one volume first, I recommend Volume 2: The Life of Greece. You can also pick up individual volumes on eBay. Durant is a magnificent writer; he can spin out a wicked paragraph. Here are some of my favorite quotations.

Any of Stephen Jay Gould’s books from the “Reflections in Natural History” series: Bully for Brontosaurus, Ever Since Darwin, Dinosaur in a Haystack, The Flamingo’s Smile, Hen’s Teeth and Horse’s Toes, The Panda’s Thumb, Eight Little Piggies. Not only was Gould a master essayist, he had a great many brilliant ideas about the nature of life, evolution, and the history of science. Some of the old ideas we love to make fun of today actually made sense given the knowledge available to people back then.

Systems of Survival, by Jane Jacobs. I’ve read Plato, Aristotle, and other philosophers about the nature of morality. They blathered away endlessly. Jacobs nailed it. She uses a rather odd dialogue structure that may put you off.

The Language Instinct, by Steven Pinker, is an excellent exposition of how language works in the human mind. He followed it up with other books on how the mind works, including How The Mind Works, The Blank Slate: the Modern Denial of Human Nature, and The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature. Of late, however, Mr. Pinker has turned to larger issues with The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, and Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress.

Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies, by Jared Diamond. A brilliant explanation of how societies have prospered or failed due to accidents of geography. Mr. Diamond has written a number of other excellent books, including The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal, and Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed.

The Moral Animal: Why We Are, the Way We Are: The New Science of Evolutionary Psychology, by Robert Wright. A bit old, but still excellent.

The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language, and the Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, both by David Crystal.

Henry Kissinger: White House Years, Years of Upheaval, Years of Renewal, Diplomacy, and World Order. You want to understand modern geopolitics? Read these.

The Alphabet Effect: The Impact of the Phonetic Alphabet on the Development of Western Civilization, by Robert K. Logan. It made mass literacy possible. And can you imagine finding information without an alphabetized index?

William McNeil: The Rise of the West

John Keegan: The Face of Battle: A Study of Agincourt, Waterloo, and the Somme. What it was like to actually be there.

Charles Fair: From the Jaws of Victory: A History of the Character, Causes, and Consequences of Military Stupidity. A little-known work that is both hilarious, tragic, and moving.

Edward O. Wilson: Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. A profound work by a great scientist on the value of seeing all of human knowledge in a single perception.

David Quammen: Monster of God: The Man-Eating Predator in the Jungles of History and the Mind; The Song of the Dodo: Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinction; The Flight of the Iguana: A Sidelong View of Science and Nature; The Boilerplate Rhino: Nature in the Eye of the Beholder. Natural history.

Scott McCloud: Understanding Comics, the Invisible Art. A truly classic work that will open your eyes about the subtleties of comics.

David Macauly: Pyramid, Castle, Cathedral, Underground, and The Way Things Work Now. Macauly has a genius for showing how big structures were built using simple tools. The first four books are fairly short, but the last is a complete exposition of just about everything technological. If you want to know how jet engines, transistors, lasers, cars, or just about anything else works, you’ve GOT to read this last book!

Daniel J. Boorstin: The Discoverers: A History of Man's Search to Know His World and Himself; and The Creators: A History of Heroes of the Imagination. These are histories of science and art, respectively.

Great Literature: I’ve read a lot of this stuff: Montaigne, Don Quixote, Poe, Jefferson, Shakespeare, etc. I don’t recommend it. Shakespeare’s vocabularly is difficult for modern English speakers to understand. The only books from “great literature” that I can recommend would be some of Mark Twain’s works: Roughing It, Life on the Mississippi, and A Tramp Abroad.

I’ll stop here; I have more books to add, but this list is already too long. I don’t expect you to read all of these books; some just won’t pique your interest. However, you should definitely set aside time for reading. I get in bed every night around 10:00 and read until 11:00. Do that for a few decades and you’ll get a lot of reading done.

I have more than 3,000 books in my personal library; perhaps 10% of those books were a waste of my time. Another 20% were of marginal value. But the rest all added something valuable to my stock of knowledge. Harken back to my discussion elsewhere on the role of narrative in thinking. There I showed my conception of the mind as a webwork of ideas:

Every book you read adds more nodes to your mental webwork. More important, it will teach you more connections between the nodes. The bigger your webwork, the better everything fits together. After many years of reading, I am starting to realize the unity of reality. It really does fit together into one big whole! I cannot communicate that whole in any medium of expression, but I urge you to discover it for yourself. It will take decades, but it’s worth it.