Step One: Recognizing your biases

First you must confront the biases that prevent you from seeing Process. The first is your primary sensory process: vision. Few people realize just how magnificent the human visual system is. It’s not just a camera; it’s a highly intelligent system that rapidly assesses a complex visual environment and provides your brain with immediately important information, carrying out a great deal of visual interpretation along the way. You don’t realize how smart it is because it all happens outside the bounds of your consciousness. If you were blessed with a guardian spirit who invisibly warded off dangers 24/7/365, you’d take it for granted and not even notice it — which is pretty much what we do with our visual systems.

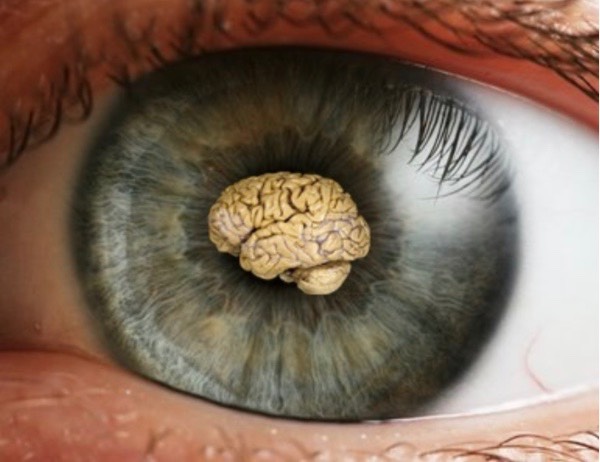

That visual system invisibly, automatically interprets the world around you as a collection of objects. Consider, for example, this image:

Your visual system is capable of recognizing a bunch of different images all smooshed together. A computer would go crazy trying to figure out what’s in this image, but your visual system is so powerful that it can disentangle all those separate images in objects. Objects. That’s what your visual system is masterful at: recognizing Objects. Not Processes. That’s the primary source of your natural bias towards seeing reality as a collection of Objects.

Another source of bias is language. Of the 1,000 most frequently used words in English, 408 are nouns, 163 are adjectives, and 40 are pronouns — all of which refer to Objects. Only 244 are verbs and 61 are adverbs — words that refer to Processes. Thus, 61% of the most frequently used words in English are about Objects and 31% are about Processes (the others are “housekeeping” words such as prepositions). We have twice as many words for Objects as for Processes.

Biology of process perception

Your bias towards Object is intrinsic to all animals; it’s the natural result of evolution. The neurons in your brain developed to provide fast response to stimuli; they fire within milliseconds. But this speed is achieved at a cost: neurons have no memory. They fire and forget. It’s possible to set up groups of neurons in loops, triggering each other in sequence, and that loop can remember something because it can keep going forever. Of course, all those extra neurons required for remembering take up a lot of space and use up a lot of energy, so the animal must eat more food to fuel all those additional neurons if it is to remember anything.

This is one of the major differences between reptiles and mammals. Roughly speaking, reptiles have no memory neurons; they live in the present. Mammals have memories, but that costs a lot of energy, so mammals have to eat a lot more food. An alligator needs about 3.25 kcal/kg/day; a human being with the same weight needs about 30 kcal/kg/day. That’s nearly ten times more energy! Now, a lot of that energy is used to maintain body temperature, a requirement that alligators don’t have. Even so, our brains comprise maybe 2% of our body weight but consume 20% of our calories.

To demonstrate the significance of this, let’s imagine a jungle floor 150 million years ago. Two small animals, a reptile and one of those new-fangled mammals, are hiding in the leaf litter. They’re both hungry, but they can hear a dinosaur stomping around in the jungle, so they remain hidden. After a while, though, the big dinosaur stomps off with a sequence of fading footfalls. The reptile hears only the individual footfalls, and so concludes that the situation is too dangerous— he stays hidden. However, the mammal heard the footfalls, too, and the mammal has enough memory to recall that the first footfall was loud, and the second was not as loud, and the third was even weaker, and so on. This memory tells the little mammal that the dinosaur has walked away—meaning that it is safe to come out and look for food. Thus, those extra neurons allow the little mammal to eat the reptile’s lunch.

This ability to remember past events is unique to mammals and birds; nobody else can do this. It gives them a huge advantage, because they can perceive their environment with greater acuity. But this requires more than just extra neurons. The mammalian brain must be able to string perceptions together into a sequence and perceive the sequence as something separate. After all, the first sequence means something very different from the second sequence:

Stomp, Stomp, Stomp, Stomp

Stomp, Stomp, Stomp, Stomp

The first sequence tells you that it’s safe to come out; the second sequence tells you that you’d better hide. But to understand this, you must ALSO know something about the world: you must know what an approaching dinosaur sounds like, and what a departing dinosaur sounds like.

You can perceive an Object instantly, with a single glance, but to perceive a Process, you must have extra neurons, use those neurons to retain an organized memory, and you must know enough about the world to interpret the sequence. Process is harder to cope with than Object. is it any wonder that people just naturally see the world in terms of Objects and not Processes?

You must recognize how steeply the playing field is tilted in the direction of Objects. You will have to exert an extra effort to break free from that bias.

Step Two: What is Process?

Process is, to our minds, abstruse. Whereas Object is instantly recognizable, Process is extended over a period of time, so you can’t immediately observe it. You must bring memory to bear to appreciate process. Of course, some Processes take place in very short periods and so can be experienced in a single moment — for example, explosions. On the other hand, some Processes are extended over such a long period of time that they are difficult for many people to grasp — for example, biological evolution. Older people have an advantage over younger people in this regard, as we have seen Processes that take place over many years, such as the growth of a tree, while younger people have experienced only fairly short Processes. Thus, I would expect that, as you age, you will find it easier to grasp Process. However, this course is addressed to young people early in their careers, so I’ll be pushing you harder!

OK, so you want a definition of Process. Here’s a simple one: Process changes Object. Object is timeless, but Process takes place over a period of time. Process is intrinsically abstract; it has no direct physical manifestation. Instead, it manifests itself in the changes to Objects. We cannot see the Process by which a tree grows, but we can see the changes in the tree.

Here’s a simple example: force. Force is one of the most fundamental processes in the universe. Force is what drives Objects to move. The most fundamental law of physics is Newton’s law: F = m*a. Force equals mass times acceleration. Yet, in all of history, nobody has ever seen a force. Forces are invisible. We deduce the existence of forces by observing the motion of objects—but we can’t ever see the force itself. Process is invisible; only Object is visible.

Step Three: Recognizing Process

In order to recognize Process, you must learn a new skill: to see with your mind:

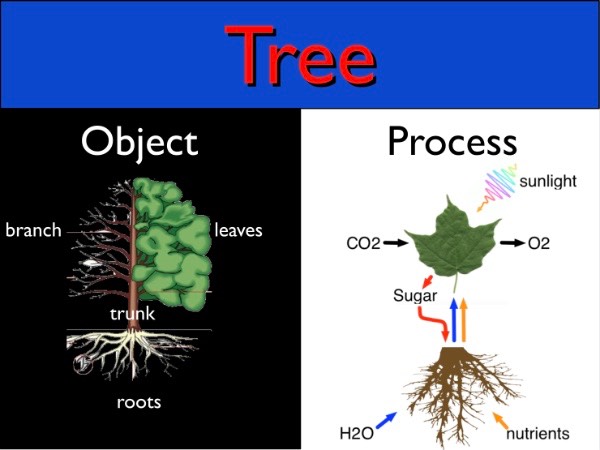

In other words, you must look INSIDE everything you see, using your mind to penetrate into not what it is but what it is doing. You can see a tree as either a collection of Objects or a system of Processes:

It’s certainly easier to see the tree as a collection of Objects; you need only know the names of the parts. But to know a name is to know nothing. Here are three people named “Fred”; what does knowing their name tell you?

If you want to truly know the tree, you must understand how it works, and that requires you to know all sorts of abstruse things about trees. You have to know the properties of water, about how minerals dissolve in water, how water moves up the tree’s trunk and into the leaves, how cells in the leaves are activated by sunlight to combine water with carbon dioxide to create complex hydrocarbon molecules — it’s really complicated! But that’s what you have to do if you want really understand trees. You cannot understand a name; you can understand only Processes. Process and understanding go hand in hand. Thus, there are two fundamentally different ways of appreciating the world:

Objects are known, but Processes are understood.

Process is everywhere. You see reality as a collection of Objects, but you can just as readily see it as a system of Processes, and just as the universe is full of Objects, it is also full of Processes. Everything that is happening in the universe is a Process at work. Motion is the result of a Process; everything going on inside a living creature is a Process; light is a Process; weather is a Process. Sure, everything you see is an Object; but everything you experience is a Process.

How to do it

Here are some activities you can play with that will give you a better idea of different systems of processes:

Electronics

Learn how to put together electronic circuits. I highly recommend that you play with the Arduino system. Amazon has a great starter kit for just $35. I can’t believe that they can offer so much stuff so cheap. If you learn everything in this kit, you’ll have a solid understanding of basic electronics. Well, not inductors, capacitors, and AC circuits, but you’ll still learn a lot.

The Way Things Work

This is a great book by David Macaulay that explains just about every technical device in the modern world. It’s whimsical, it’s beautifully illustrated, and it’s well written.

Meteorology

Most people care about weather predictions but never bother to understand the weather. This stuff is fascinating! The way storms work, especially thunderstorms and hurricanes, is amazing. Did you know that a single big hurricane generates about 200 times as much power as all the power plants on the planet put together?

Evolution

Sure, we all know that species evolve, but the mechanics of how this happens will surprise you. Stephen Jay Gould wrote a whole series of books on life and evolution. Read ‘em all!

There’s also some great stuff on human cognitive evolution: The Mating Mind, by Geoffrey F. Miller, The Prehistory of the Mind, by Steven Mithen, and anything by Robert Wright, except Why Buddhism is True.

Linguistics

This is especially important if you want to understand how humans can talk to computers. There are a million great books on linguistics. Start with The Language Instinct by Steven Pinker then go on to read all of his other books. Or try David Crystal’s Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language and his Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language.

Economics

I know, I know, econ courses are about as dry as you can get, but economics itself is much more interesting than the economics professors let on. I suggest that you learn economics by reading The Economist, a news magazine unlike any other. I think it might better be called “Contemporary History” because its contents would fit right into a history book in the future. The Economist presents what’s important instead of what’s exciting. No airplane crashes, gory crime stories, scandals, or gossip about politicians here. Not that many pictures, either.

Military History

As a young man, I studied military history because, as a member of the Vietnam generation, I wanted to understand why humans kept on fighting each other. I never found the answer, but what I did find was that some of the best minds in history have tried to master the principles of warfare. A good starting book would be John Keegan’s A History of Warfare. Most books on military history are just “battle books” describing “the world’s greatest battles”—as if a battle could be great. I do recommend From the Jaws of Victory, but it’s quite rare.

History

Read Will Durant’s The Story of Civilization. Do it. Now. Is that understood?