Appendix from Guns & Butter

August 19th, 2010

This was created in 1989 to help players understand the internal structure of the game; I wrote the text and Amanda Goodenough drew the wonderful illustrations.

After-Dinner Conversation

“That was an excellent dinner, Florin. Please congratulate your chef for me.”

“Thank you, Embert. He certainly did an impressive job tonight.”

“That wine — it’s Rhenish, isn’t it?”

“I have no idea; I have never pursued oenology. YOU are the man of wealth and taste.”

“So I have been called,” Embert laughed. They had reached Florin’s study, a simple room with two very comfortable chairs, no decorations, a desk and table, and a fireplace that was not in use. Florin swept up her robe with her arm prior to seating herself.

“So tell me, Florin, have you reconsidered that silly theory of yours?”

“To which silly theory do you refer, Embert? I have so many.”

“I have in mind your latest perambulations on the economics of cultures.”

“Oh, yes, THOSE! Yes, those ideas are particularly pretty, aren’t they? I must admit, I do take special pleasure in the cleverness inherent in those ideas.”

“I will surely concede their cleverness — you have always been a dazzlingly creative thinker. But the undeniable cleverness of the conceptual structure in no way alters the simple fact that they are flat, dead, wrong. Impressively clever, yes, but still wrong.”

“Well, then, Embert, you will be frustrated to learn that I have indeed reconsidered the matter (largely at your behest), and that I have further developed and even extended the conceptual structure.”

“Oh, no! I should have known. Ah well, I suppose that it will supply grist for tonight’s discussion. Where did we leave off last time?”

“As I recall, we had reached an impasse over the role of technological innovation. To plunge right back into it, I reiterate: technological innovation plays no primary role in the economic development of a culture. I know that you find that assertion incredible, but let me develop the point:

“I am not arguing that technology itself has no impact on economic development; that point should be patent. Rather, I focus more narrowly on technological innovation. Suppose, for example, that we were to inject the knowledge of, say, plows, plowshares, the tri-annual rotation system, and so forth into a Stone Age tribal culture. What good would it do them? They couldn’t use the knowledge if we gave it to them. Even if some Stone Age Einstein were able to figure it out for himself, to single-handedly invent plows and harnesses for oxen and the techniques of long-row plowing, it would do no good whatever. A tribal group of a few dozen individuals couldn’t afford to use the technology. Who would build the harnesses for the oxen? Who would care for the oxen? Who would make the storage bins for the grain? Who would maintain the calendar so necessary for successful agriculture? It just couldn’t be done by a group that small.”

“But Florin, you take your arguement too far. You argue that technological innovation has no impact on economic development. What about the myriad serendipitous discoveries that have changed so many histories? What about Oersted reversing the wires, or that Phoenician fellow who discovered glass in his campfire, or Smith and penicillin? Surely you will not relegate these acts of intellectual heroism to some statistical dustbin, dismissing them as ‘fluctuations’?”

“Indeed I shall, Embert. I readily concede that some discoveries came earlier than they should have, but it is equally true that some came later. The decisive factor was not the earliness or tardiness of the discovery, but the receptiveness of the culture to the discovery. To cite an easy case, the Vikings discovered the New World 500 years before the Spanish, but their culture was not receptive to the discovery, and so nothing came of it.”

“But why were the Vikings unable to exploit the discovery? (I shall overlook for the moment the fact that it was not strictly a technological discovery.) Was it not because their culture was simply not attuned to colonization, and instead pursued other goals?”

“But is not colonization itself an expression of population? An underpopulated culture does not think in terms of colonization. Only when a culture reaches a certain population density does colonization acquire any value. Had Viking culture been more populous, perhaps they would have initiated colonization of the New World. And this arguement brings us straight back to my central thesis about population and progress.”

“Ah, yes, Florin’s direct equation: progress through population. Better living through procreation. I cannot believe you would entertain a hypothesis so easily countered. What about China, a nation swimming with people for so many thousands of years? Or India, a nation equally blessed? What about the Third World nations of the twentieth century? Their exploding populations should have guaranteed sensational economic progress, but in fact the reverse happened. Moreover, the hypothesis cannot even be held to be original; Marx himself zeroed in on expanding markets as the underpinning of capitalism.”

“Well, I think that we should dismiss Marx right now. I’ve never understood the man’s theories, especially after the French got ahold of them.”

They both laughed.

“But to address your historical observations: yes, you have a good point about excessive populations. But remember that China’s failure was a very near run thing. They were making excellent progress there for a long time, and I really held my breath when they sent that expedition to East Africa in the 1400s. They came so close, but they lost it. I was really rooting for them. But the Europeans beat them to the punch.”

“Yes, I really got you on that one, didn’t I? Your genteel Chinese couldn’t quite pull it off. They turned inward and lost their edge, overpowering with their stultifying self-assurance even the invading Mongols and Manchus. Your theories certainly fell apart there! Meanwhile, my feisty Europeans set about taking over the globe.”

“Yes, you nailed me on that one. What did that cost me? A dinner?”

“A dinner and that black obsidian orb of yours. I keep it in my meditation tower.”

“Ah, yes, I miss that orb. Ah well, I deserved to lose — I was wrong. But this time I am not wrong. I am quite certain that population growth is the primary factor in economic development. I concede that there are many qualifying considerations, such as the degree to which population expansion creates a labor surplus, but I will insist that the core issue in a culture’s economic progress is population growth.”

“You insist, eh? Do I detect a challenge in that word? Are you leading up to something?”

A wry grin spread over Florin’s face. “Actually, no, I wasn’t leading, but now that you mention it, I think that I would be willing to try another experiment with you. What will be the stakes?”

“If I am right, I want that perfect feather quill that you keep by your table.”

“And if I win, I want my black obsidian orb back.”

“Done!”

“Very well, Embert, let us design our experiment. I shall create a planet with four billion different continents.”

“Why so large?”

“Because I want a proper statistical foundation for our work. I’ve always felt cheated by the ways things came out on Earth. You must admit, it really was a fluke.”

“A fluctuation, you mean? I thought fluctuations didn’t matter.”

“They shouldn’t matter. Really, didn’t the denouement of that experiment leave you feeling dissatisfied?”

“Not I, old friend; I can understand your frustration with an ending that you would characterize as startling, but I found a reassuring irony in it. It was so, so... [he paused, searching for the word] ...so very true to form for them.”

Florin laughed. “Indeed it was. Although I must say, the line I shall always remember was Hitler’s.”

“Which one was that? There were so many memorable ones.”

“I refer to his comment upon learning that he had just triggered World War II: ‘What do we do now?’”

Embert howled uproariously, slapping a thigh. “Oh, yes, yes, that was choice. That was the best.” He wiped a mirthful tear from his eye. “You know, I truly outdid myself with him. I zeroed in on the essence of those people, their psychology. He certainly proved a lot of my arguements. Yes, I don’t think I’ve ever done as well as with him. But I digress. We were discussing your new planet. You shall have four billion continents. That is acceptable to me. Why don’t we begin immediately with that?”

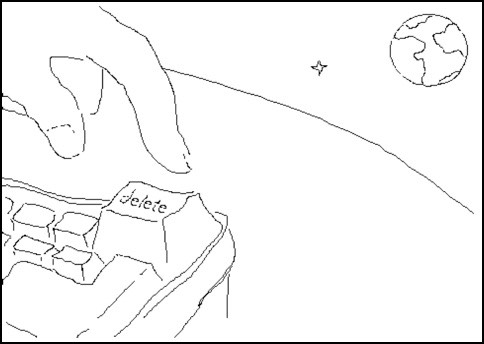

“Capital idea, Embert.” Florin leaned up from her seat and called into the next room:

“Gabriel! Bring me my keyboard!”

Gabriel appeared bearing The Keyboard of Creation. With an overly theatrical flourish he placed it on the table in front of Florin. “Will there be anything else, madam?”

“No, thank you, Gabriel. You are dismissed.”

“Very good, madam.”

Designing a Planet

They set to work, Embert crowding over Florin’s shoulder as she fired up the machine.

“Now then, good Embert, what shall our continents look like? Shall they have mountains and forests and deserts and islands and lakes and other good terrain features?”

“Yes, I do think that you should include the mountains, forests, and deserts, as we can make them the choicest locations for acquiring certain resources. Some areas will be well-endowed with crucial resources, while others will be cursed with shortages of resources. That will force our protagonists to cope with one person’s surplus and another person’s shortage. What a lovely way to encourage lively competition!”

“Hold a moment, my warmongering friend. I agree that we do need to encourage territorial disputes by distributing natural resources unevenly, but we must not take it so far that a particularly unfortunate mortal would never be able to get his economy started. We must provide that the mortal cursed with poor terrain still have enough resource that he can get started.”

“Ah, my bleeding-heart friend, why must you always soften the harsh realities? If some mortal is cheated by territorial circumstances, why would you want to reverse that verdict?”

“Because it would ultimately make the game less interesting. Do you really want the outcome to be determined by the mere luck of the random number generator? What would that prove? Don’t we want to see how cultures interact economically? How could a connoisseur of war like yourself take any pleasure in the sight of a rich and powerful nation squashing a poor and weak one?”

“You are right, of course. Thank you for correcting me. Let us provide a modicum of natural resources to each mortal, augmented by a bounteous supply for those blessed with the proper terrain.”

“Well and good, Embert. Now, what about other terrain features? Do we want lakes and islands?”

“I should think not, Florin. I think that we should remove all maritime factors and make this a strictly land-based environment. We have spent months debating the role of maritime factors in the social evolution on Earth, and we never did reach any agreements. It was simply too complex. The transition from a land-centered regime to a maritime regime coinciding with the fall of Byzantium…”

“No, Embert, the transition came earlier than that. Fully 54% of all trade tonnage in 1300…”

“You see, we still cannot agree on anything. I must say, at first I liked your ideas about water-borne traffic, and all those rivers and seas everywhere to make certain that the humans would be able to transport things at a very early stage of their social evolution. But we were never able to agree on what it all meant! We debated endlessly and fruitlessly. Let’s leave maritime stuff out this time, just for simplicity’s sake. Please?”

Florin laughed. “Very well, Embert, I will forego my preference for seaborne activity. Just for you. So, we won’t have any lakes or islands or maritime geography. Anything else?”

“How about a few volcanoes spewing lava, and perhaps the occasional earthquake with yawning crevices swallowing people and horses, and…”

“That’s another game, Embert.”

“Yes, I know. Sorry.”

“Very well, I think that we have the physical geography down pat. Now, how about the political geography? Shall we just go ahead with our standard provinces-cum-countries system?”

“I don’t know, Florin, it seems so staid. Every planet we’ve done had provinces making countries. Can’t we come up with something better this time?”

“Be my guest, Embert.”

A long pause followed. Embert paced about, hands clasped behind his back. Several times he jerked to a stop with a sentence pregnant upon his lips, only to hesitate and swallow the thought. At length, his shoulders slumped.

“Very well, Florin. Provinces and countries.”

“If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Now, what about roads connecting provinces?”

“Oh yes, I assumed that we would have some roads. But how many? Should every pair of adjacent provinces be connected by roads?”

“Surely we can do better than that. Let’s say that, oh, only half of the adjacent provinces are connected by roads. The others will have no connections other than the simple adjacency.”

“Ooh, ooh, we can put the forests, mountains, and deserts into those places where there aren’t roads!”

“Capital idea, my man! Yes, let’s! And that suggests another simple idea: attacks down roads are easier than attacks across borders without roads.”

“Why, Florin, you’ve never been one to take interest in the finer points of military technique. I’m pleased to see you taking some interest in the subject.”

“Some of your voluminous knowledge on the subject had to rub off on me. Now then, let’s see how it all adds up.”

Florin had been tapping away at the keyboard as they spoke, translating their ideas into code. Her fingers flew across the keyboard in a grey blur, the lines of code rocketing across the screen. Like a concert pianist reaching the crescendo of her piece, she completed her work with a dramatic flourish and melodramatically pressed the carriage return, then looked up at Embert with a self-satisfied smile. Embert glanced down at the screen, paused, and then looked up at the ceiling. Alarmed, Florin looked back down at the screen. “What!?!?! It refused to compile?!?! What’s wrong with this thing?”

“Um, perhaps, dear Florin, just perhaps you made some minor programming error.”

Florin’s fists clenched and she sat more erect. “You forget, friend Embert, just who I am. Remember, I am omnipotent, omniscient, and infallible.” She paused, and then said slowly, evenly, and with great emphasis on each word:

“I...DON’T...MAKE...PROGRAMMING ...ERRORS!”

Florin set to work examining the precise nature of the problem. After a few moment’s effort, she uttered a triumphant cry and pointed at the offending item. “There, there it is! The language specification calls for this class of records to be infinitely dimensionable, but the compiler writer decided to restrict it to three dimensions and never declared the restriction. Damn that compiler writer!”

“Florin! do you mean that literally? Do you wish to consign him to my care?”

Florin glanced up, realizing that she had lost her temper. She started to correct herself, then hesitated, thought for a moment. A wicked smile slowly crept across her face. Very softly she said, “Yes...yes...why don’t you take him? Truly he deserves it. Yes.” She smiled with great satisfaction for a moment. Then she sat up and muttered, “Back to work.” It took a few moments to program around the flaw in the compiler. “There. All done now. Let’s try it out.” Once again she pressed the carriage return to engage the compiler, albeit a little less melodramatically this time. They watched with satisfaction as the program compiled properly and launched. It created the planet and built something vaguely like continents. “Oh my!” Embert exclaimed. “That’s not right at all. Oh, dear me!”

“Of course, how silly of me! In my rush to correct that stupid compiler problem, I overlooked that possibility of word overflow on one of the variables. It’s all that compiler writer’s fault. Will you see to it that he occupies one of the less temperate climes?”

“But of course, my friend. I suppose that we shall have to dispense with this abomination of a planet?”

“Yes, yes, let it go.” Florin pressed a key. Somewhere in space, a malformed planet exploded into atoms. On the next try, it came out right. They looked over their new planet with satisfaction.

“Perfect! Perfect! This will serve our purposes admirably! Florin, you’ve done it again!”

Population Design

“Very well, what shall we do now?”

“I suggest that we consider the population structure of each country.”

“There isn’t much to consider, is there? Each province has a population and a certain amount of farmland. The farmland is just enough to feed the existing population using the primitive methods available at the beginning of the game.”

“Let’s give them a small surplus to permit some opportunity for economic growth.”

“Very well, a small surplus it is. Now, we shall lump together all the populations in all the provinces to create the labor force for the entire country.”

“Embert, is that wise? Shouldn’t there be some sort of transportation limitation on the economy of each country? I am uncomfortable with the idea of just lumping everything together without any consideration for transportation factors.”

“But Florin, do we really want our subjects to devote their energies to getting the train schedules running smoothly? You know how complex a task that can be. Why tax their little minds with large problems that do not ultimately bear on the matters we wish to explore?”

“I suppose so. It’s just that I have always been so fond of trains and boats.”

“Well, we can do a Transportation Planet next time.”

“Very well. On with the design!”“We were considering the population of each country. Now, how should that population grow? I suggest that population grow in proportion to food surplus.”

“That makes sense. For simplicity, let us declare that one ton of food per person per year will sustain life with no population gain or loss. Less than one ton will lead to population decline, more will lead to growth.”

“What should the function look like?”“Well, we don’t want it to be too harsh. Let’s allow food supplies to fall to, say, about half a ton per person before we start to get severe population decline.”

“Fair enough. On the other hand, though, we shouldn’t be too generous with population growth. I certainly don’t want anything like a linear function.”

“Most certainly not. We can’t have them doubling their population merely by doubling their food surplus. Let’s put in a nice diminishing returns function — how about a square root?”

Food Functions

“Yes, that should work just fine. Yes, indeed. Now, how about food production? How should we have that work?”

“Well, as I see it, there are three factors that will control food production: acreage, labor supply, and machinery.”

“The acreage will be fixed by the stock of provinces in the country. What about the labor supply? I suppose we’ll need some sort of function that will permit diminishing returns for increasing numbers of workers per acre.”

“You know, Embert, we could greatly simplify matters by freezing that variable.”

“What? Freeze the number of workers per acre? That’s crazy! Why would you want to do that?”

“Well, in the first place, our experience with Earth indicated some stability in that number across a wide range of circumstances. The only strong exception was the rice-growing culture of East Asia, which had very high labor densities. But the wheat and cereal growing regions exhibited a remarkable stability in the number of workers per acre.”

“Towards the end there was a precipitous decline.”

“Yes, that’s true, but I think we can safely skip that. And think how much it would simplify the system!”

“That’s certainly true. Freezing agricultural labor at one worker per acre would eliminate one degree of freedom from the situation. Yes, I’ll go for that.”

“Good. Now we have just one variable left to tackle: machinery.”

“Which is, of course, the dominant one for the purposes of our study. What we need is a sequence of agricultural tools that are increasingly powerful.”

“I would greatly prefer to see the progression be one of regular increases in the utility of the succeeding tools.”

“Dear Florin, you are certainly being structured this time around. Where are all those creative flourishes you used on Earth, or the baroque creativity you expressed with Lamina? Are you losing your flair?”

“Not at all, Embert. I want a nice, simple planet this time around. We spend so much time arguing the intricacies of the matter that this time, I want something with no intricacies.”

“I am hurt, Florin. Have you lost the enjoyment of our discussions?”

Florin leaned back from her key-board and laughed. “No, no, Embert, that’s not it at all. I just want to crucify you this time around, without any intricacies to obstruct my intellectual assault.”

“Well and good — I shall be on my guard. To return to the subject at hand: you wanted a simple progression in the increases in utility of agricultural devices. Would a factor of two be simple enough for you?”

“Each succeeding agricultural tool is twice as productive as the previous one? Yes, that sounds straightforward enough. It appeals to my sense of order.”

“What shall we call them?”

“We’ll make up four or five. It doesn’t matter what we call them. The locals won’t know the difference.”

“I would impose this constraint on the sequence: not only should the productivity of each tool increase in a regular geometric fashion, but the production cost should also increase geometrically, but at a lower rate. Thus, as the mortals move along the technological curve, they enjoy greater efficiencies.”

“Very well. I suppose that we shall want to start off with simple farm tools and move all the way up to tractors.”

“OK. I’d like to see iron plows and irrigation systems, but that makes only four. Can you suggest at least one more?”

“Well, we are lacking a tool from the middle Industrial Revolution period. The farm tools and iron plow are pre-Industrial Revolution, and the irrigation and tractor are post-Industrial Revolution. That does leave a historical gap that we must fill.”

“Hmm, what about a cotton gin?”

“No good — too narrow in application.”

“Very well, how about a steam-driven combine? It will require use of the steam engine. We do have a problem with the steam engine. Its primary application on Earth was for transportation, railroads and steamships, but you have eliminated transportation considerations, so our planet’s occupants will simply skip the steam engine. That seems such a shame. This would correct the problem.”

“I like that. We have five agricultural technologies.”

“Now it’s my turn. We must discuss the weapons technologies that we will make available to our mortals.”

“Ah, yes, I knew this would come. Look, I am prepared, with some reluctance, to concede the necessity of conflict, weaponry, and war. But can we make it a little less bloodthirsty this time?”

“But conflict is the acid test of our theories. War is the great judge of societies, the wolf that purges the herd of its weaklings, the cleansing agent that sweeps away all that is false and weak. Look what happened when we held back the barbarians from the Roman Empire. The damn thing slowly rotted, smothering the European peoples with its putrescence. Attila was the best thing that could have happened to Europe, and you stopped him!”

“Now, I’ve told you before, I only intervened at the Po Valley in 452. I felt that there was still some life left in Rome, and I could not stomach those Huns tearing everything down. But I had nothing to do with the battles of Campus Mauriacus or Nedao. Those were fair fights, good examples of what you call ‘the cleansing agent’. It was your Huns who were swept away, fair and square.”

“Humph! I suppose so. Still, the Huns had a lot of bad breaks. Attila’s death had to be one of the worst.”

“Sympathy for the Huns, eh? Sorry, Embert, I don’t feel it. Now let me counterattack. If war is such a purifying agent, what about the Great Plains American Indians? Their culture institutionalized perpetual warfare. At puberty, a boy became a warrior, not a man. And the result was an utterly stagnant culture. Those people wasted 10,000 years while almost every other culture on the planet made great strides forward. And don’t give me that line about ‘lack of resources’. The Indians of the Great Plains were surrounded by gigantic herds of bison, a food surplus that should have touched off a population explosion, but they never could get their population to increase because they were always killing each other. Even sparing the women and killing only males, they still couldn’t get a population increase. The direct result of their warlike attitudes was that they were still in the Stone Age when the Europeans arrived.”

“That’s true, Florin, but recall what the Europeans did to them: they wiped them out! War corrected the problem!”

“I’m sorry, Embert, but you haven’t convinced me. I will concede, though, that some amount of warfare is necessary. I think that we can work together within that compromise, don’t you?”

“Yes, of course, my good friend. Tell you what — as a gesture of goodwill, I propose that our sequence of weapons stop short of atomic weaponry. No nuclear weapons, ICBMs, ABMs or any of that good stuff. Let’s stop with tanks. I can have enough fun with them. Fair enough?”

“A noble compromise! Done!”

“So we shall have tanks at the top of our sequence and, what, um, swords at the bottom?”

“If you don’t mind, Embert, I would prefer not to participate in this part of the design. Feel free to devise any reasonable sequence you fancy.”

Embert laughed. “Very well, I shall do so. Let’s see, I suppose that we should follow up swords with firearms. What firearms do I want? Arquebuses, muskets, culverins, bombards, field cannons, howitzers — there are so many from which to choose.”

“Please don’t drag this process out.”

“Very well, I shall keep it simple. I shall follow swords with muskets, rifles, cannons, and lastly, tanks. That’s five. Good enough?”

“Fine. Now we must move on to what is perhaps the most difficult task we face: the definition of all the commodities used in the economy and the relationships between them.”

“I was afraid of this one, Florin. I presume that you want to keep things simple.”

“Yes, I think we should strive for the simplest possible structure. Rich enough to demonstrate the principles, but not so messy as to dominate the economic interactions.”

“We have agreed on the end products, agricultural tools and weapons. Now, should we work up from raw materials or down from the end products?”

Transcriber’s note: There followed a tedious and extended discussion of the merits of nearly 100 different raw materials and intermediate products and their natural interrelationships. The two interlocutors went to great lengths to examine every one of the many millions of mathematically possible combinations. After much trial and error, a coherent set was finally obtained, but not before the patience of the transcriber was exhausted. The transcription resumes at the agreement.

“So let’s go over it one more time, shall we?”

“Please, Florin, let’s!”

“For raw materials, we have lumber, coal, sulfur, iron ore, light metals, heavy metals, petroleum, and nitrates. Agreed?”

“Agreed. My list of intermediate materials now includes charcoal, pig iron, iron, low-grade steel, high-grade steel, gunpowder, explosives, and high explosives. That’s still eight, yes?”

“Unless the complexity of this discussion has addled my arithmetic powers as badly as it has yours. What does our list show for machinery?”

“I have steam engine, wire, pipe, electrical devices, ball bearings, diesel engines, and instruments. How many is that?”

“It’s only seven, but we can live with it. I just can’t accept iron parts as a prerequisite for anything else.”

“OK, OK. I think we have it. You have the input/output diagram for it?”

“Right here.”

“I must tell you, Florin, I am not at all comfortable with this structure. I’m not suggesting that we should go back over it one more time; I think that we have driven this one into the ground. My fear is that the thing may still have holes in its structure, holes that we will not be able to divine.”

“Embert, if I had intended to make flawless economic systems, I would have made them that way. Part of the fun of all this is seeing how it works out, yes?”

“I suppose so. So now let us turn to another bedeviling issue: the mechanics of production. Land, labor, and capital. How shall we balance these factors this time around? I have a truly novel suggestion: let us dispense entirely with capital in all its forms.”

“WHAT!?! Embert, is this another one of your jokes, like that planet with the non-commutative sexual relationships? I felt so sorry for those poor people…”

“Hey, what’s the point of creating all those worlds if you can’t engage in a bit of levity?”

“Indeed! What about all those particles you kept foisting on the earth physicists?” Florin chortled. “You got them started with the simple proton-electron-neutron triangle, but then came the mesons, baryons, and leptons, and then the neutrinos, and then when they started getting close, you really went wild. Quarks! Those were great! How did you ever think up anything so funny?”

“I don’t know what got into me. I considered the whole thing an intellectual challenge, but the little buggers kept going to higher and higher energies, and I had to keep making up new and better schemes to keep them at bay. Once the joke got started, I couldn’t stop it — you can imagine what their reaction would have been had they discovered the truth. I’m just glad that they were so good at translating laboratory results into weaponry so quickly. It sure got me off the hook.”

“Yes it did. Imagine — a blue quark bomb. Oh, well.”

“Well, this time, I am not joking. After all, what is capital but the accumulation of the product of labor? And do not all capital assets depreciate?”

“Yes, but many of the largest capital assets depreciate very slowly indeed.”

“HOW slowly, Florin? How long does it take the typical capital asset to depreciate?”

“Well, that depends on the capital asset in question. Some assets depreciate in years, while others take decades.”

“There IS a pattern, though. In general, capital assets do not last longer than the average lifetime of the builders. After all, who wants to expend precious resource creating an asset whose returns will not be fully realized in one’s own lifetime?”

“There are many cases of societies building capital assets whose lifetime greatly exceeded the life of an individual. The Pyramids, the gothic cathedrals, the great bridges and dams — there are thousands of counterexamples to shatter your claim.”

“But every one of those counterexamples was a public work, undertaken not for private profit but rather for the public good. Moreover, every one represented an investment too large to be undertaken by private concerns. If we restrict our considerations to business activities undertaken for profit, I think that you will find that my generalization holds water.”

“I suppose so. But what is its significance?”

“Just this: if we use a long enough time scale in monitoring economic activity, everything depreciates! If we use as a basic unit of time the life span of an individual, then all capital assets will depreciate away in a single unit of time. And that means that they can be ignored!”

“I am not willing to completely dispense with capital; its role in economic development is absolutely undeniable. And how do you explain the accumulation of wealth that is always associated with economic progress?”

“I do not propose the total elimination of capital from the economy, only its elimination from our direct involvement. In effect, each generation creates its own capital. In any real system, the creation and depreciation of capital is an ongoing process. At any given moment, slightly more capital is being created than depreciated, and so the net stock of capital grows. What I am proposing is the artifice of gathering all the creation for a single generation into a single instant at the beginning of that generation, and also gathering all the depreciation for a single generation into a single instant at the end of the generation. This vastly simplifies the behavior of the system from our point of view, does it not?”“I must admit, it is a brilliant way of simplifying an otherwise knotty problem. I will readily concede that the handling of capital assets is a truly infernal problem. Your scheme does banish that problem. But I must insist that you recognize this as a gross simplification.”

“Oh, yes, I will gladly concede that point. A simplification, yes; but one whose clarifying effects make it worth the sacrifice.”

“Very well, I accept your proposal. We shall have no capital assets in this planet. The workers build the factory in their youth, use it to make product in their maturity, and decommission it as they retire.”

“Very well, we have eliminated capital from our considerations. Now, what about land and labor?”

“We have already established the basic land factors: farmland, forest for lumber, mountains and deserts for other raw materials. I think we are in good shape there. All that remains is labor.”

“You know, Embert, I begin to appreciate the novelty of your system. An economic structure dominated by labor. Do you think we should fetch Karl Marx to look in on this once it is complete? He would surely think that he had died and gone to heaven!”

“Please, don’t reward my creativity with exposure to that long-winded bore! Don’t you recall how we fought over who would be stuck with him?”

“OK, OK, we’ll leave Karl out of this. Now, back to labor. How shall we handle it?”

Productivity Functions

“I deem it absolutely essential that we provide a solid basis for economies of scale. Productivity must increase as an exponential function of labor.”

“Agreed. But there are two issues we must tackle. First, should the proportionality constant in the productivity function be the same for all industries, and second, should the exponent be the same for all industries?”

“Well, let’s figure it out. If we use the same proportionality constant for all industries, that implies that workers in different industries would be equally productive. If it takes five workers to produce 1000 tons of coal, then it would take five workers to produce 1000 tons of, say, electrical instruments. That doesn’t make much sense, does it?”

“Obviously not.”

“So our proportionality constants must differ across industries. I further believe that we must have different exponents. Old technologies, simpler and more labor-intensive, would enjoy smaller economies of scale, expressed mathematically in a lower exponent in the productivity function. Newer and more complex technologies would, I presume, require more in the way of capital and less labor, permitting them to enjoy larger economies of scale, and hence we would want to use larger exponents.”

“But aren’t you going too far? After all, who will be able to appreciate such subtleties? Do you really think that the mortals will be able to figure out the differences between industries with differing proportionality constants and exponents?”

“Probably not. But even if they don’t understand it, the system must still work. The more advanced industries must have smaller proportionality constants and larger exponents so that they are less efficient at smaller scales and more efficient at larger scales. This is an essential component of technological progress. Without it, we would have 15th century peasants building digital watches. In effect, my economies of scale theories link with your population theories to insure that technological progress parallels population increase.”

“Embert, you do seem to have quite an infatuation with economies of scale. Is this your latest interest?”

“Yes, I have been quite taken by the notion of late. I suppose that what got me started on this was the realization that economies of scale are nothing more than an operational expression of the essence of toolness. Bigger and better tools cost more but are more efficient. That’s just a rephrasing of the notion of economies of scale. It’s really quite fascinating.”

Technology Transitions

“Florin, I would now like to turn to the difficult problem of technology transitions. It is vital that the mortals move through the technological sequence that we have created in a regular and orderly fashion. I am concerned that this might not happen.”“Come now, Embert, it should be easy. Each technology in the sequence is twice as efficient as its predecessor. That should be motivation enough to guarantee an advance up the ladder.”

“Actually, we may have to worry that the motivation might be too much. What if an iron plow is twice as productive as farm tools, and costs only 50% more? Surely our subjects would move immediately to the iron plow.”

“But Embert, that is precisely our intention!”

“Yes, but we don’t want it to happen too soon. If we fail to adjust the equations properly, we might well see 16th century peasants riding tractors.”

“I see your point. How can we balance the equations?”

“I believe that we need to use exponential functions to express the economies of scale. To make advanced technologies more productive at the high end of the production scale, we need to give them larger exponents. And to hold their value down at the low end of the production scale, we need to give them small multiplicative coefficients. The trick then will be to balance the system of equations to guarantee that the entire set of equations (one for each technology) fits together properly. I think that it all turns on selecting a good set of crossover points.”

“Well, what if we initialize the situation such that the mortals start halfway up the scale with the lowest agricultural technology. That way, they will only need to double output to saturate that technology, and when they make the transition to the next technology, it will automatically be halfway toward saturation (because it is exactly twice as productive).”

“This implies that crossover points will be spaced at neat intervals of factors of two in output. I like that. The only remaining issue is to set the boundary conditions. Just how many workers should it take to handle all this?”

“The boundary condition is established by our initial population and our desired growth rate. If they put all their labor into building agricultural tools at the lowest level, then the labor supply should be just large enough to create enough food to achieve, say, 30% growth.”

“Fair enough. This still requires me to balance the system of equations. Ugh! I’d better get cracking.”

Military Factors

“You know, Florin, we have been avoiding the all-important issue of military operations. I realize that you find the matter distasteful, but it is incumbent upon us to address it now.”

Florin sighed. “Yes, I know, Embert. Let’s get it over with now. How do you want to handle this?”

“Well, we have already figured out the source of military power in production. The only tasks are the actual application of military power. First off is the problem of getting the weapons from the factories to the field.”

“I would very much like to minimize this element of the system. Can’t we just make it happen automatically?”

“Florin, you can do anything you want. Sure, we can make it automatic. How, though, can we insure that the automatic process makes sense?”

“What if weapons are distributed each turn in proportion to the previous turn’s concentration? If you had concentrated forces in one province on turn X, then on turn X+1, weapons will be sent to that province.”

“I like it! Yes, that is very clean. OK, so now we turn to problem of combat results computation. Province A attacks Province B; how do we calculate the winner?”

“You do this, Embert.”

“Very well, here goes: we don’t want to encourage too much attacking, so let’s put in some attack penalties. First off, I suggest that the attacker automatically lose 10 firepower points, and the defender fights with an extra bonus of 10 firepower points. This will discourage attacks with small forces. I hate it when somebody wins a victory with trivial forces. I want to see Combat! Battle! Not some petty skirmish leading to conquest. OK so far?”

“I would prefer not to have such automatic bonuses — they won’t make sense to the locals. Your proposal presumes a standard calculation of the ratio of attack strength to defense strength. What if instead we use the difference between the two rather than the ratio? That would automatically solve the problem of minimum attack strength requirements.”

“Hmm, you make a good point. I suggest that we defer to a Higher Authority on this matter.”

“Very well, Embert; you do the honors. I take my normal position.”

Embert reached into the folds of his gown and brought out an ancient coin. He flicked it high up into the air with his thumb. Both parties watched it spin higher and higher, just missing the vaulted ceiling, and arc down. Embert’s eyes glanced down to catch Florin’s attention; he grinned impishly before looking up again to follow the coin as it fell into his extended palm. He slapped it down hard onto the back of his hand.

Then he slowly raised the hand, with coin still covered by the other hand, up to his face. Casting a facetiously suspicious glance at Florin, he raised one finger of the covering hand ever so slightly and peered underneath it for a few long seconds. Then he looked up at Florin, took a deep breath, and announced: “Heads — I win!”

“Very well, Embert: strength ratios with additive penalties and bonuses.”

“Next, I think we should have a strong terrain penalty. Let’s say that the attacker is quartered attacking across terrain.”

“What do you count as terrain?”

“Anything that isn’t a road. Attacking down a road, you fight with normal strength, but anywhere else, your strength is quartered. That should force some sense of strategic maneuver onto our subjects.”

“Anything else?”

“Hmm...oh, yes, we need a provision for the effects of the battle on the civilians. After all, they are the ones who pay the highest price. I suggest that we reduce the population of the attacked province by the amount of military power that the attacker brought to bear on the province. That way, a big conquest will wipe out the population and dramatically reduce the value of the province. Scorched earth, so to speak.”

“Leave it to you, Embert, to remember these fine points.”

“Ah, but I am done now!”

Economics Unions

“Good! Now we have one last problem to address, and we are done. How are we going to prevent runaway growth in the eight-nation continents?”

“I don’t see the problem.”

“Consider the question, at what point does one nation obtain an unshakeable lead over all the others?”

“That wouldn’t happen until that nation has 51% of the total resources on the continent.”“No, it would happen much earlier. Remember, we have large economies of scale on this planet.”

“I still don’t follow you. What do economies of scale have to do with this?”

“Economies of scale in production imply that a 2:1 superiority in population translates into a greater-than-2:1 superiority in production. Hence a nation with 51% of the total population will have much more production than all of the other nations combined. In fact, given the strong economies of scale we have set up for this planet, a nation with only 25% of the total population could still produce more than all the other nations combined!”

“How could that possibly happen?”

“Here, I’ll walk you through the numbers. Suppose that one nation has 25% of the total population and the other seven have 11% each. Suppose further that all other factors are equal and that the economies of scale work out to a cubic power in this case. Thus, the leading nation, with a population superiority of 2:1, ends up with a production superiority of 8:1. If all of the smaller nations throw all their production against the largest nation, the combined production ratio is 8:7 in favor of the larger nation. He’s got a lock on victory with only 25% of the population base!”

“Mon dieu!” Embert stood stunned and speechless for a moment. “What are we going to do?”

“It’s obvious that we must somehow permit smaller nations to engage in some form of economic cooperation that enables them to enjoy the benefits of economies of scale.”

“Hold it right there, Florin! Are you about to drag me into some sort of trade scheme again?”

“Well, that was not my intention, but I will point out that trade would solve our problems handily.”

“No good, Florin. We’ve been through this once before, with Planet Hubert. Don’t you remember what a disaster that was?”

“But you must admit that trade worked well on Earth.”

“That was different. On Earth, we decentralized trade. It was handled by millions of earthlings in millions of tiny transactions. It became a statistical function out of the direct control of the policymakers. It worked well that way. In fact, it worked so well that any attempt on the part of the policymakers to influence the trade process only garbled the process. It was funny, I admit, watching the poor fools struggling with a phenomenon that was out of their intellectual grasp. They’d twist the trade policy one way, and the currency valuations would jerk around to correct the problem, and then they’d try to stabilize the currency, and round and round they went, never getting on top of it. Yes, it was funny. But there was a clear message: trade cannot be handled by direct control. It’s too intricate trying to match up two economies by hand. The matching must be done statistically.”

“But would’t it be possible to create some sort of statistical arrangement for trade?”

“That’s exactly what we tried to do with Hubert. Remember how that came out? We used that central store concept of yours to even out fluctuations in prices and supplies, and so the Hubertans spent all their energies interacting with the damned store! They bought and sold wildly and never noticed each other. And when we started twisting the numbers away from the store, they were unable to form a decent economy. Remember, a stable economy requires a perfect marketplace, and the half-dozen actors we placed on Hubert were insufficient to create a perfect marketplace. We needed a hundred different countries to make that work.”

“But, Embert, we NEED trade. Without it, the biggest player will have a lock on victory.”

“We need something, I agree, but trade won’t work unless there are many countries to assure stable supplies of and demand for every commodity. Without the smoothing effects arising from large numbers of countries, trade breaks down. Admit it, Florin, trade is a statistical concept that works only in large decentralized systems. And such systems are outside the range of the tightly controlled experimental system we are setting up here.”

“But do you have any alternative?”

Embert paused. He had been on a roll in his condemnation of trade. Now he had to change gears and was momentarily off balance. He hummed and hawed for a moment. “What if we allow them to directly merge their economies?”

“What?!?! Simply merge their economies, just like that?”

“Well, yes, and why not? We’re working at such a large scale here that it seems appropriate to me. After all, are not close trade relationships extended over a long time a form of economic integration?”

“Integration falls well short of union.”

“True, but as a simplifying model, union expresses the concept, doesn’t it?”

“Let me hear a proposal.”

“OK, here goes. We allow nations to merge their economies for single turns. While merged, all their assets are pooled. They enjoy the benefits of economies of scale. They distribute the fruits of their labors, both military and agricultural, in proportion to the labor supply they brought to the pool. At the end of the turn, the union is dissolved.”

“Who makes the economic decisions for the union?”

“Its sponsor, the person who declared the union. Anybody who joins a union surrenders economic sovereignty to the leader.”

“Why should anybody do that?”

“First, what’s the joy in figuring all those economic balances? Second, joining a union makes you stronger than you would be alone. It’s worth it.”

“It’s a radical idea. We’ve never tried anything like this before.”

“Is that any reason not to try now? After all, it’s just an experiment, a game. Besides, consider the interesting advantages that accrue from this. Think of all the interesting diplomatic interactions that arise from this system. Consider how quickly a player could rise or fall with the fortunes of his unions. Without unions, the planetary situation focuses on economics and military factors. The unions make it a triangular interaction between economic, military, and diplomatic factors. Now that’s interesting, don’t you agree?”

“You’ve convinced me. Let’s do it!”

“Done!”

And they did it.