I recently had a run-in with a typical young gamer guy on the question of whether games can be considered to be art. He is absolutely certain of this, but his certitude much exceeds his knowledge, as demonstrated by the fact that he deems the hit game “Elden Ring” to be the artistic equal of the movie “Chariots of Fire”. Sheesh!

Not having played the game, I read a description of it on Wikipedia, then watched several explanatory videos on YouTube demonstrating the game play, including the detailed descriptions of the subtleties of fighting. It’s pretty much the same old, same old stuff: run around, gather weapons, armor, etc, fight off a variety of bad guys, then take on the bosses at each level.

But our testosterone-drenched young fellow rejected my estimate of the game on the grounds that I had not actually played it. Without playing the game, he avowed, one cannot possibly know it.

Here’s a fossil tooth:

This thing is about seven inches long. It is the only fossil remnant of a long-extinct species. Nevertheless, just from this tooth (and others much like it), paleontologists have been able to reconstruct the creature that bore the tooth:

This cuddly creature is known as the megalodon, and it’s about 30 feet long. How were paleontologists able to reconstruct this creature from just a tooth?

Context provides them with all the information they needed. It’s very similar to the teeth of modern sharks, and nothing at all like the teeth of any other known species. They therefore concluded that it’s a form of shark. That got them 95% of the way. The only other problem was to figure out the size. This was done by simply scaling up what we know about the relationships between the size of teeth and the size of sharks across a great many shark species. Poof! That’s all it took.

Here’s another example of a fossil and its reconstructed creature:

“How did they figure out all that extra detail that’s not in the fossil?” you ask. Again, context provides the additional information. This fossil was found to be a bit over 500 million years old; that gives them a general idea of the biological constraints on the creature. They know that it had to somehow obtain oxygen to sustain its metabolism; that’s what the five little holes are for. By bringing into consideration everything what’s known about the animals of that time and the biological and metabolic constraints upon those creatures, paleontologists can fill in a great deal of material.

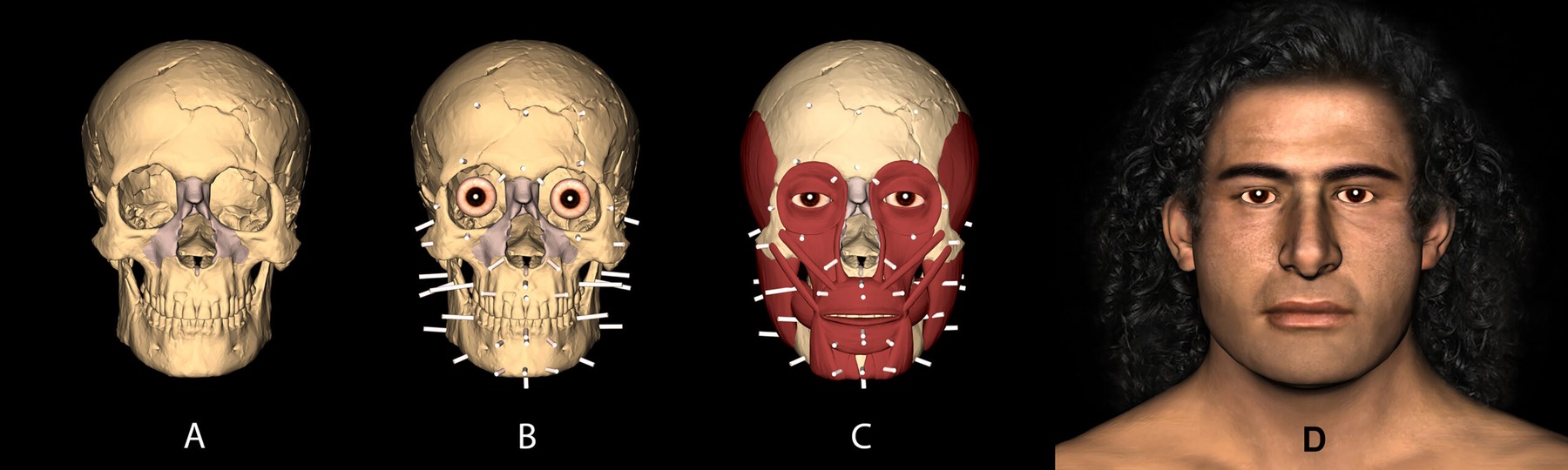

Here is yet another example: facial reconstruction from ancient skulls. Knowing the anatomy and dynamics of the human face, scientists can reconstruct a person’s face from their skull. For example:

(Credit: Professor Jack Davis and Dr. Sharon Stocker)

They don’t know the data of the person’s face, but they understand the processes by which faces are built, and that context permits them to reconstruct the face.

There are plenty of other instances of context helping to answer questions. For example, it was common among ancient historians to greatly exaggerate the size of the opposing armies — that made the victory of the good guys look all the grander. But modern historians have been able to correct some of these numbers by consulting contextual evidence. I once read an analysis of the battle of Marathon in which the historian, by digging up numbers on the number of ships available to the Persians, showed that the claim by Herodotus that the Persians had over 800 ships was surely exaggerated.

So What?

What is the significance of all these dreary examples? Simple: you don’t need to have all the empirical data to be able to draw reliable conclusions from a scant supply of data, IF you have plenty of contextual information. This is why the young fellow’s claim that I didn’t know what I was talking about because I hadn’t played the game is wrong.

Games exist in an ocean of context. There are hundreds of games released each year, and in the 45 years since I started in the games industry, I have played hundreds of games and seen thousands. Moreover, games don’t show much diversity; all the big-budget games hew closely to a standard set of features. The A-level games where the player runs around killing things, especially with swords and magic spells — those are far and away the most common species. In terms of biodiversity, the world of A-level games is like a ranch: a lot of cows, some horses, maybe some goats and pigs — and that’s it.

Moreover, the community built around games has been stable for decades. It consists almost entirely of young men, aged early teens to early 30s, who are often, shall we say, rather geeky and weak on social skills. There are standard places to discuss games, standard places that review games, and standard places that sell games. The whole universe of games is standardized.

Hence, I was able to grasp the content of Elden Rings with just a few minutes of watching a training video on YouTube.