The simple story they tell you in school about Copernicus is wrong on many counts. In the first place, that wasn’t his real name; it was his Latinized name, used for official Church correspondence. His real name was Mikołaj Kopernik. He was a Polish priest and something of a genius. This guy could speak Latin, German, Polish, Greek, and Italian. His doctorate was in mathematics, he sometimes served as a doctor, he carried out several diplomatic missions, was an able administrator of Church properties, and on top of that, he developed a concept in economics now called Gresham’s Law: less reliable currencies tend to be used in the marketplace, while more reliable currencies tend to be hoarded.

But it was as an astronomer that Copernicus made his mark on history. Actually, he wasn’t an astronomer in the sense that we think of the word. All of his astronomical work was directed towards providing better tables of planetary positions for astrologers. Astrology was the money-earner in those days; astronomy was very much a “who cares?” kind of thing.

Astrologers needed good tables of planetary positions in times past and future. If King Bigshot asked you to cast his horoscope, you had to figure out where the planets were at the time of his birth. If your tables were inaccurate, some other astrologer might accuse you of fraud, so it was very important to get good tables of planetary positions.

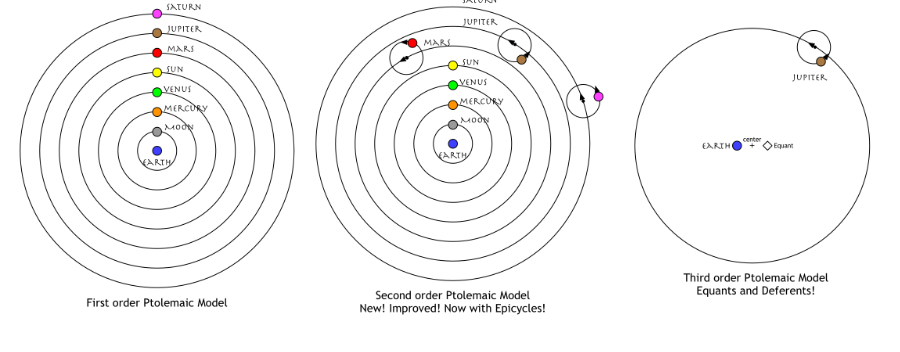

Most people used the Ptolemaic model of the solar system. This was the standard model that put the earth in the center of the universe, with the moon, the sun, and the planets orbiting the earth in perfect circles. The problem was that it produced lousy predictions. They had quickly patched up the problems by adding epicycles, but then they had to add equants and deferents:

I have shown only Jupiter in the third order Ptolemaic model because it gets too complicated. The Equant pushed the earth away from the center of the circular orbit; you don’t want to try to figure out how a deferent worked.

This scheme worked fairly well. You could always fiddle around with the values for each planet’s epicycle, equant, and deferent to “correct” its performance. Unfortunately, no matter how much they fiddled around with the numbers, they just couldn’t get planetary tables that matched observations over long periods of time.

Copernicus had one big idea: we can get rid of the epicycles if we put the sun at the center of the universe, like so:

Now we come to a crucial point: Copernicus did not think that this was the way the solar system was really laid out — at least, not at first. Remember, he was just trying to come up with a scheme to calculate better planetary tables, and he realized that this scheme would save a great deal of time. Remember, these people were carrying out all the calculations on paper, and mistakes were frequent. Having done calculations similar to this with a calculator and with a computer, I can assure you that calculating just one set of planetary positions on paper would have taken days. Thus, at first, Copernicus saw this as nothing more than a computational trick to save labor.

It is difficult for me to communicate the magnitude of Copernicus’ effort in working out his model. His book, De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium, is massive and it works its way through its calculations with every single step worked out. There are literally thousands of calculations of immensely complex geometric figures showing the various orbital positions and the many angles subtended by all the lines drawn around them. It truly is mind-boggling. For years, it was said that De Revolutionibus was ‘the book nobody read’, because nobody could possibly have the patience to plow through all those calculations. I myself followed one calculation from beginning to end, and it took me several hours to check it out and reassure myself that he got everything right.

Ironically enough, Copernicus’ heliocentric system didn’t produce results any better than the geocentric model; its tables of planetary positions disagreed with the tables produced by the geocentric system, but they weren’t any better at matching the observations. That’s because Copernicus was still fixated on the notion that the orbits of the planets were perfect circles when in fact they are ellipses.

Copernicus worked on his book for over twenty years; he refused to publish his work until the results matched the observations better. He also came to realize that the geocentric model, with its epicycles, was absurd. This in turn meant that the heliocentric model was likely closer to the truth. The Church (remember, Copernicus was a priest) had pronounced the geocentric model to be correct, so it would be heresy for Copernicus to contradict the Church. Still, Copernicus was convinced that the heliocentric model was the correct one. Moreover, a number of high-level Church officials were impresssed by what they had heard about Copernicus’ work.

We are lucky that a dedicated fan traveled to Poland to encourage Copernicus to publish it. Copernicus was ill and sensed that death was approaching, so he reluctantly agreed. The young fellow helped him tidy everything up, and then took the manuscript to Germany for publication. Copernicus wrote a prefatory note explaining that he felt that his heliocentric model was superior to the geocentric model. However, the printer in Germany rewrote the prefatory note to say that the heliocentric model was a computational device only, and not representative of the real world. Copernicus died before he received the final printed book.