While Arabic-Hindu numerals were slowly creeping into common usage, the theologians continued their quest to “glorify God through understanding of his creation” (that was the line Aquinas used to get past Christian conservatives). The problem of Aristotle’s thrown rock continued to plague them, but the big break, as I mentioned earlier, came when the Oxford Calculators tackled the problem using arithmetic. Four members of this informal research team are most prominent: Thomas Bradwardine, William Heytesbury and Richard Swineshead. Of these, the unfortunately named Swineshead was the most important; indeed, one historian ranked him as one of the ten most brilliant minds in history.

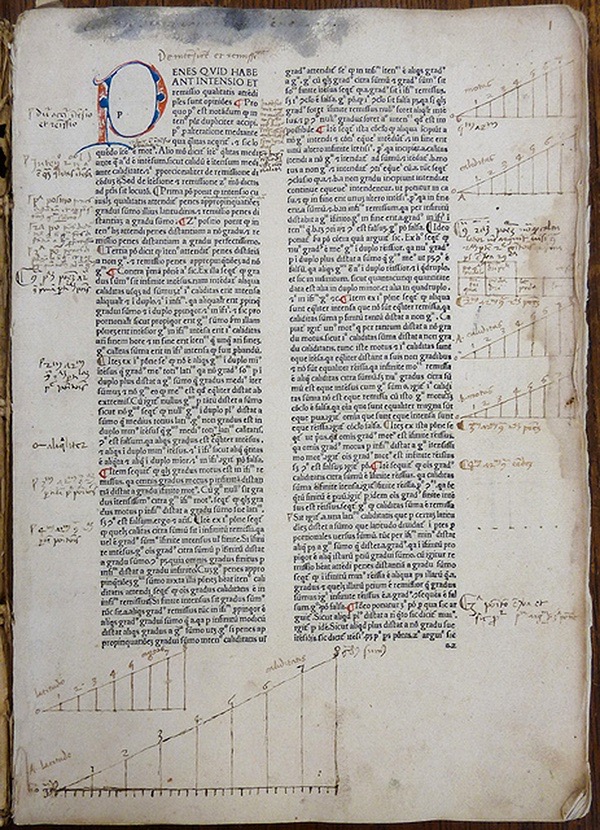

This page from a later printed version of one of Swineshead’s books shows the crucial concept: the graphs:

This concept predates deCartes (remember “Cartesian coordinates”?) by 300 years. It doesn’t quite go as far as the full graph; note that there is no y-axis. Nevertheless, these guys figure out the way to express the motion of an object graphically and numerically. They never came up with the algebraic expressions of their ideas, but they broke a crucial barrier: they applied numbers to the understanding of physical phenomena.

One other thing: every one of these scholars was an ordained Catholic priest. Far from being an obstacle to the advance of science, the church was the sole source of intellectual progress for over a thousand years, from 500 CE to 1600 CE.

Next up: Copernicus takes the next big step.