July 4th, 2020

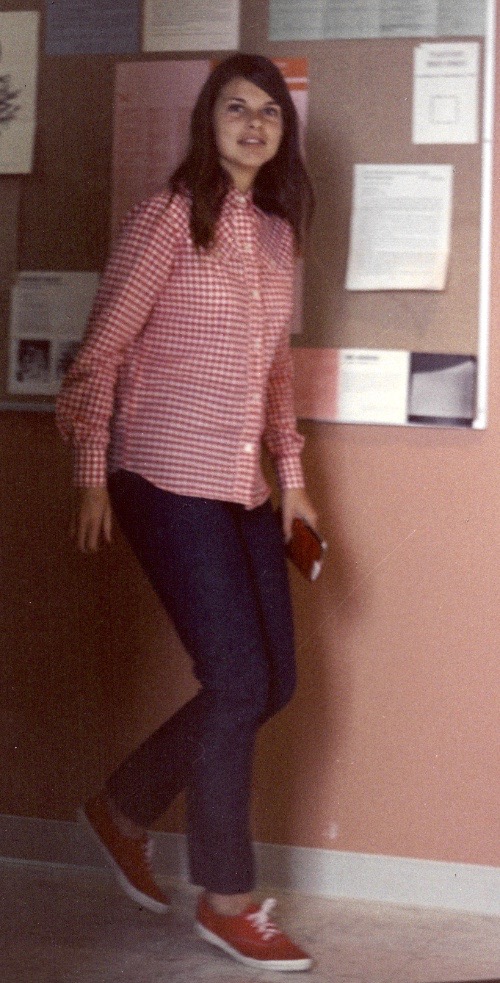

Gemma was my first girlfriend. This is a photo I took of her at the time:

I’ll never understand why she liked me. I was completely self-absorbed, and although I was never hurtful to anybody, I was a clueless geek. I couldn’t believe that a beautiful girl like Gemma could see anything in me. Many years later I asked her what she saw in me. She said that I was “interesting”. I think she just felt sorry for me. I was, after all, a pretty sorry person back in high school.

I lost track of her after she broke up with me. She came down with a serious case of cancer and was told that she had only a few years to live. She signed up for an experimental chemotherapy program that very nearly killed her, but it killed the cancer and she survived, although her internal organs were seriously damaged by the chemotherapy.

Gemma went on to marry a fellow who treated her like dirt; they eventually broke up. Later, she got into another relationship with ANOTHER guy who treated her badly. After that, she swore off men.

I happened to run into Gemma in the early 1990s; she was studying for a doctorate in biochemistry. I met her at the lab; with great excitement she showed me some DNA that she had just isolated. It was a tiny speck of white in the bottom of a conical test tube. Her eyes sparkled with enthusiasm. Here she is at age 22 and age 50. She’s just as full of life and joy at age 50 as at age 22.

I visited her as often as possible, and we often spoke on the telephone.

Gemma was the most loving human being I have ever known. She loved everybody; I think that’s why she chose such lousy boyfriends. She loved music and played the violin; after her fingers gave out, she sang. For thirty years, she did volunteer work at an animal rescue facility; she cared for raptors:

Gemma was a teacher; she taught genetics and physiology at UC Berkeley; she also trained high school teachers at another college. She loved her students and spent endless hours helping them. She loved teaching and carried on teaching right up until she retired just a month ago.

The chemotherapy that saved her life in 1972 ravaged her innards. She was the perfect patient; she got lots of exercise, ate all the right things, and, with her expertise in physiology, she was often more knowledgeable than her doctors about her condition. But over the years her health declined. I visited her twice this year; we talked about death. She knew that she was dying, but wasn’t worried. She would fight it to the bitter end, full of joy and love for everybody. She was tired and weak, but she was still Gemma through and through:

Her heart was failing, she was walking a biochemical tightrope requiring exquisitely careful balancing of phosphorus and potassium in her body, but she wasn’t intimidated. I spoke to her seven days ago. She was very weak and could only talk for a few minutes before she had to lie down.

Gemma died last night, in her bed, in her house surrounded by people who loved her; everybody loved Gemma and wanted to help her in any way they could.

Gemma was the finest and best human being I have ever known. I am a lesser person now that she is dead; the world is a lesser place.